By John Brightman Brock

A former soldier has told a story of war from experience – his father’s and his.

[column width=”1/4″]

Learn more from the author at Archives exhibit

The Museum of Alabama’s new temporary World War I exhibit, “Alabamians and the Great War,” opens in the museum’s new Alabama Treasures gallery on Nov. 9 at the Alabama Department of Archives and History, 624 Washington Ave., Montgomery. Author Nimrod T. “Rod” Frazer will talk at 2 p.m. about his new book, Send the Alabamians.

The new gallery is filled with actual relics from the war years of 1914-1918, and is highlighted by graphic panels depicting life on the front lines. “It was a war that affected everyone, whether you had a relative in the war or you didn’t,” Archives and History Director Steve Murray says. “We have terrific things – from uniforms to the flags of some of these units. These are beautiful banners, bright colors and in some way are special in conveying visually the process of Alabamians re-entering the union. We are talking about a period that is barely 50 years removed from the end of the Civil War.”

The exhibit is presented in honor of Frazer by his colleagues at Enstar USA, Inc. With so many contributions, “We have some artifacts that we don’t have room to display,” Murray says, so a rotation plan is being devised.

For more information, visit www.archives.alabama.gov, or call 334-353-3312.

[/column]

The son, a decorated officer who once served in Korea, pursued an education. His father, country-boy poor, had only the glory of being among the heroes of often-forgotten World War I.

Almost a century later, the younger soldier set out to make things right.

Almost a century later, the younger soldier set out to make things right.

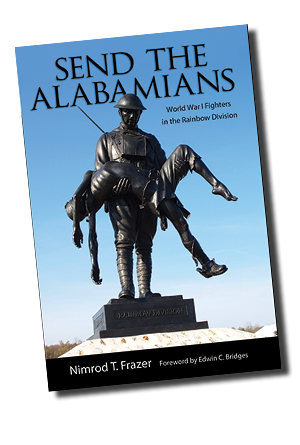

For more than seven years, Nimrod “Rod” Thompson Frazer, a retired investment banker from Montgomery, researched and documented his book, “Send The Alabamians,” published in May by the University of Alabama Press. He tells the journey of his dad, Will Frazer, and 3,700 other Alabamians in the 167th U.S. Infantry Regiment of the famed 42nd “Rainbow Division.”

“Our scholars and educators have for the most part ignored a very important part of Alabama history that was written with the blood of mostly poor 3,720 small town and rural Alabamians. Real combat soldiers, they fought with distinction in France in 1918,” Frazer said recently in an interview from his home. “The last serious book about the regiment was written in 1919. I set out to make a fully authentic account of the combat of the 167th Infantry Regiment in World War I.”

But for Frazer, this is not just a historical account.

“Will was dead when I wrote the book,” Frazer said. “As a common soldier, he probably knew little of what was going on, only that he was in all the fighting.” A handsome man at 20, proud and tall, Will wrote a fine hand, but admitted to only seven grades of schooling. He joined the Alabama National Guard at age 19, in 1916, and served on the Mexican border before going to France as a corporal and squad leader.

Will Frazer was wounded early in the battle to take the Aisne-Marne, Croix Rouge Farm, a fight that raged from July 24-26, 1918; 162 Alabama soldiers were killed in just one four-hour period.

During the attack, Will Frazer crawled into a shell hole after being hit twice in the upper part of his right leg. “Will was in the hole with a French soldier and a dead German,” Frazer wrote. “Eventually, the French soldier motioned for Will to stick his head up to see the Germans’ location. Will motioned back for the French soldier to do so. He complied and was killed by a single bullet to his head.”

Will’s regiment, in the war’s only hand-to-hand fighting, halted the death toll that had claimed millions of lives. In the climactic battle of Croix Rouge Farm in France, the regiment incurred the most Alabama losses since Gettysburg.

Their division, so-named after Douglas MacArthur said it stretched like a rainbow across the United States, was one of the first American divisions committed to full combat after President Woodrow Wilson broke off relations. The division, always led on point by the 167th, “the Alabam,” would turn the tide of victory. After the armistice was signed, newspapers called them “the Immortals” upon their return to Alabama in May 1919. Their fame, it was thought, would be timeless.

The author, 84, saw significant combat in Korea, gaining the Silver Star and Presidential Unit Citation for gallantry in action and service. The father of five, two of whom “wore the uniform,” later successfully transformed The Enstar Group, became successful in business real estate and was inducted into the Alabama Business Hall of Fame in 2008.

Memories of his dad, his youth and a forgotten world war still linger with Frazer. For a time, Frazer walked the battlefields of France. Not a historian, he admits that researching and writing the book was “the hardest thing I’ve ever done.”

“My mother was something of a hero worshiper, which is probably why she married him,” Frazer said about his father. “They lived in Greenville until she left him shortly before my seventh birthday, in 1936. My early years were spent in the Montgomery household of my maternal grandfather for whom I was named. He regularly sent me to visit my father but I never again lived in my father’s household. Our common bond was interest in the military and the 167th Infantry.

“Not talkative about anything, his only glory came from serving in (nearly) every battle of the 167th. Our most meaningful conversations came when I was on the way to Korea and when I returned home,” he said. “By then I was going to Columbia, then Harvard. Will was ashamed of his poor education and told me he had regretted it every day for 50 years.

Will had tried operating a storefront laundry and dry cleaning business, and eventually lost it. Every day, he had battled alcoholism, and he died at age 77 in Greenville.

“But this war … gave these boys glory,” Frazer said of his dad’s regiment. “It was glory. For some of these boys, it was the only glory they had ever known.”

Frazer used an impressive amount of primary sources. Research took him to France seven times, to the National Archives four times, to Carlisle Barracks, the Mexican Border and the Philippines. The final draft of Frazer’s book submitted to the University of Alabama Press had about 1,400 footnotes and many direct quotes from the soldiers themselves.

This summer, 200 people attended a commemoration – as they do each year – of “The Alabam” regiment in France. They laid wreaths near a statue memorializing the regiment, at the site of the Croix Rouge Farm battle. Frazer earlier had bought the battlefield and deeded it to the nearby Town of Fere en Tardenois, to carry on the annual remembrance.

“Send The Alabamians” is a graphic, intense return to the machine gun-strafed battlefields and mustard gas-filled trenches of France. These men, ages 18 to 28, most of whom had never traveled out of Alabama, became the point men for Gen. John J. Pershing’s victorious war effort. “In time of war, send me all the Alabamians you can get, but in time of peace for Lord’s sake, send them to somebody else!” quipped Gen. Edward H. Plummer, who once commanded the men.

The author will host a book talk at 2 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 9 at Alabama Department of Archives and History’s Montgomery museum, in conjunction with the opening of the new “Alabama Treasures” exhibit.