By Katie Jackson

Fire in the hills. That’s what American naturalist William Bartram thought he was seeing when he rounded a wooded bend on the Savannah River in the late 1700s and saw an entire hillside ablaze with red and orange color.

It wasn’t fire that Bartram saw, however. It was a stand of native Flame azaleas blooming in all their intense glory, a sight that is increasingly rare these days in the wild, but is being preserved and expanded by a dedicated cadre of modern-day horticulturists.

Native azaleas, often called bush honeysuckles, are relatives of the white and pastel-colored landscape azaleas that herald spring in Alabama. Both types of azaleas are members of the rhododendron genus; however, those iconic “Southern” azaleas actually originated in Asia and were brought here via England in the 1800s. Native azaleas, on the other hand, have been here since long before humankind was around to appreciate their beauty.

Native azaleas, often called bush honeysuckles, are relatives of the white and pastel-colored landscape azaleas that herald spring in Alabama. Both types of azaleas are members of the rhododendron genus; however, those iconic “Southern” azaleas actually originated in Asia and were brought here via England in the 1800s. Native azaleas, on the other hand, have been here since long before humankind was around to appreciate their beauty.

Though related, Asian and native azaleas have distinct differences. For example, native azaleas are deciduous, not evergreen, like their Asian cousins, and native azaleas bloom in a palette of colors from gentle whites and pinks to brilliant yellows and intense oranges and reds.

Of the estimated 17 species of native azaleas in the United States, most are found along the east coast and a dozen or more of those are native to the Southeast. Depending on the type, those Southeastern native azaleas can range in height from knee high up to 15 feet at maturity and have bloom times in spring, summer or early fall.

Groups working hard to preserve and expand species

Sadly, habitat destruction has severely diminished many pockets of wild native azaleas, but groups of guardians are working hard to preserve and expand native azalea numbers. Those guardians can be found throughout the state and beyond, including one enclave in east central Alabama.

Among that group is Robert Greenleaf, emeritus professor of music at Auburn University who has some 300 different native azalea varieties growing around his Auburn home. The son of an Auburn University horticulture professor, Greenleaf remembered seeing native azaleas in the woods when he was young. When he came back to Auburn as a music department faculty member in the 1970s, Greenleaf began planting them around his house site.

His collection expanded thanks in large part to two local plantsmen, Tom Corley and Dennis Rouse, who had been collecting and hybridizing wild native azaleas for years and shared their seeds with Greenleaf, who was soon hooked on the plants.

“They are attractive, noninvasive and very hardy,” Greenleaf says, adding that growing them is extremely rewarding — so much so that he is attempting to have one of every available native azalea variety on his property, where he intersperses them with other trees, shrubs and herbaceous perennials for a stunning natural display.

Patrick Thompson, a specialist at Auburn University’s Donald E. Davis Arboretum, is also a member of this east central Alabama cadre. He became immersed in native azaleas when the late R.O. Smitherman, another Auburn man who worked with Corley, Rouse and others to increase the native azalea gene pool, donated several hundred plants to the arboretum beginning in 2008. The plants came from Smitherman’s own collection of several hundred selections from thousands of varieties and hybrids, a collection that included “Corley’s Cardinal” and “Patsy’s Pink,” both of which Smitherman registered with the Royal Horticulture Society.

For several years since, Thompson has been evaluating Smitherman’s donated plants for performance in east central Alabama and at other sites across the state. He’s also been propagating them and now has enough to sell five dazzling varieties to the public, with more coming available soon (see them at http://thomppg.wix.com/auburnazalea). He’s also become a native azalea evangelist.

More fragrant, with more nectar and pollen

“Both (native and non-native azaleas) have their merits,” says Thompson, who is the current president of Alabama’s Azalea Society of America chapter, but he’s especially fond of the native ones.

According to Thompson, native azaleas are often more fragrant and produce nectar and pollen throughout more of the year than their imported relatives. Those traits draw bees and butterflies as well as birds (including hummingbirds) and other animals to them, ultimately helping sustain the local ecosystem.

“That’s a missing link in a lot of gardens,” says Thompson, noting that non-native plants often can’t provide such ecosystem support.

For that reason, and because of their beauty and hardiness, native azaleas are a great option for home landscapes. Thompson noted that native azaleas may not be as abundantly available as their Asian counterparts, but they can be purchased from growers who specialize in native plants and often at native plant sales sponsored by public gardens and civic groups across the state.

Though the best time to plant native azaleas is in the fall (see the sidebar for planting tips), now is an ideal time to see them blooming at locations across the state such as the Davis Arboretum, the Huntsville and Mobile botanical garden and other public gardens and along many of this spring’s azalea trails (Auburn’s trail goes right past Greenleaf’s house).

Or go into the woods and keep your eyes open. The hills may well be on fire.

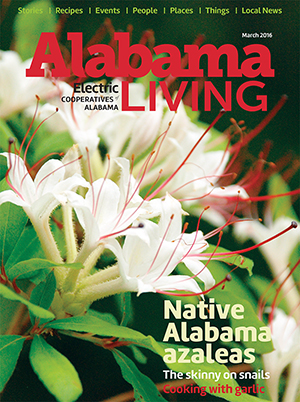

The azalea in our cover photo was grown from a plant originally found on Mt. Cheaha. This clone of that plant can be found perched above the waterfall at Auburn University’s Donald E. Davis Arboretum. The late R.O. Smitherman, who donated many native azaleas from his collection to the arboretum, said it was the only species of azalea you can hear. Reports the arboretum’s Patrick Thompson: “We would be walking along a straight stretch of creek bank and when he heard the sound of falling or rushing water he would perk up and say, ‘Hear that? Sounds like arborescent.’ He was right too often to have been finding all those plants for the first time.”The flowers are often solid white, sometimes with a yellow blotch, and always with red pistil and stamens. The cover photograph was taken in late April, but the plants growing wild on Lake Martin, Hallawakee Creek and other places bloom as late as September and may one day be described as a new subspecies. It has been referred to as Rhododendron arborescens georgiana.

The azalea in our cover photo was grown from a plant originally found on Mt. Cheaha. This clone of that plant can be found perched above the waterfall at Auburn University’s Donald E. Davis Arboretum. The late R.O. Smitherman, who donated many native azaleas from his collection to the arboretum, said it was the only species of azalea you can hear. Reports the arboretum’s Patrick Thompson: “We would be walking along a straight stretch of creek bank and when he heard the sound of falling or rushing water he would perk up and say, ‘Hear that? Sounds like arborescent.’ He was right too often to have been finding all those plants for the first time.”The flowers are often solid white, sometimes with a yellow blotch, and always with red pistil and stamens. The cover photograph was taken in late April, but the plants growing wild on Lake Martin, Hallawakee Creek and other places bloom as late as September and may one day be described as a new subspecies. It has been referred to as Rhododendron arborescens georgiana.

Establishing native azaleas in your landscape

Once they are established, which may take up to three years, native azaleas offer low-maintenance beauty to the landscape and are ideal as understory plants or in partially shaded areas. If planted correctly, they need little if any pruning and fertilizer and have few pests.

Because they need a loose, well-drained and well-aerated soil with a pH of about 5.5, it pays to get a soil test and amend soils accordingly with any needed nutrients and lots of organic matter before planting.

To ensure proper establishment, plant native azaleas in the late fall by following these steps recommended by native azalea aficionado Robert Greenleaf and the Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

Dig a hole about 2 to 3 feet wider than the root ball and deep enough so that about half the root ball will remain exposed above the ground.

Amend the soil with a mixture of one part ground pine bark, peat moss or other organic matter to one part soil (a 50/50 blend).

A soil pH of about 5.5 is ideal for native azaleas. If your soil is extremely acidic or alkaline you may need to adjust the pH using limestone amendments. (In his part of east central Alabama where soils tend to be acidic and high in phosphorus, Greenleaf uses 1 cup of dolomitic limestone to ½ cup gypsum per wheelbarrow of soil mix.)

Place the plant in the hole and mound the soil mixture over the root ball.

Mulch with 2 to 3 inches of pine straw, ground pine bark or other organic mulch.

Water deeply and slowly a couple of times each week for the first 6 to 8 weeks, then weekly thereafter during dry spells.

Continue to water the plant regularly, add new mulch and remove weeds as needed.

Take time to enjoy the blooms and all the creatures that visit those blooms!

More information on native azaleas and their maintenance is available through the Donald E. Davis Arboretum at www.auburn.edu/cosam/arboretum/, the Alabama Cooperative Extension System at www.aces.edu, the Azalea Society of America at azaleas.org. or through many botanical gardens and native plant nurseries in Alabama and the Southeast.