By Scotty L. Kirkland

The Alabama Department of Archives and History (ADAH), the home of our state’s history since 1901, includes the Museum of Alabama, the state’s official history museum. More than 30,000 people visit the museum every year, including thousands of schoolchildren. There they find delights and curiosities aplenty, particularly in Alabama Voices, the centerpiece exhibit that covers the dramatic unfolding of Alabama history from the dawn of the 1700s to the beginning of the 21st century.

More than 800 artifacts and hundreds of images and documents tell the story of struggles over the land, the rise of a cotton economy, the Civil War and Reconstruction, industrialization, world wars, civil rights, the race to the moon and much more.

A “top ten” list for an exhibit such as Alabama Voices is a subjective thing, influenced by age, personal interests and any number of persuasions. This, of course, is the beauty of a well-designed museum: There is something for everyone.

In late May 2025, Alabama Voices will close temporarily for updates reflecting recent scholarship, new artifact donations and upgraded audiovisual components. This work is part of a series of improvements as the ADAH prepares to mark 125 years of service to the people of Alabama and for the 250th anniversary of the founding of the nation in 2026. The objects listed will remain on exhibit once these renovations are completed.

Portrait of William McIntosh

Born ca. 1775, William McIntosh was the son of Senoya of the Wind Clan and Captain William McIntosh, a trader from a prominent Georgia family. In time, young McIntosh became head of the tribal town of Coweta and an important Creek figure.

Brothers Nathan and Joseph Negus, itinerant artists from Massachusetts, painted the portrait at McIntosh’s request in the spring of 1821. His clothing depicts a mixture of Native, European and American cultures, clues to his own sense of fashion and identity in an era that witnessed both the blending of cultures and sometimes violent displacement of those who first called the land of Alabama home.

Four years after the portrait was completed, McIntosh was executed by order of the Creek National Council for signing an unauthorized land treaty with the U.S. government. In 1832, his son sold the portrait to the owner of a Columbus, Georgia, tavern, where it remained for 90 years until one of the owner’s descendants sold it to the ADAH in 1922.

Note: The painting is currently undergoing a professional cleaning and conservation offsite. A photographic reproduction is currently on view in Alabama Voices.

Key to the State Capitol at Cahaba

Four locales served as Alabama’s capital city before Montgomery. St. Stephens was the territorial capital from 1817 to 1819. Huntsville was the temporary capital at statehood in 1819. Soon thereafter, Cahaba (sometimes spelled Cahawba) in Dallas County took the honor. It was a controversial choice but the site favored by Gov. William Wyatt Bibb. A land rush ensued. Cahaba lots that once sold for $1.25 an acre soon fetched $60. The nascent government of the state grew quickly in the Black Belt soil. By 1821, there was a well-appointed state house, multiple other buildings and businesses and more than 1,000 residents.

But the bubble burst in 1825 when the Legislature voted to relocate the capital to Tuscaloosa. The streets of Cahaba quickly fell quiet. Today, little remains of this early capital city. The site is now an archaeological park managed by the Alabama Historical Commission. A “ghost structure” offers a glimpse of the state house.

Perote ballot box

During the turbulent years of Reconstruction, the ballot box became a powerful symbol of both freedom and fraud. Under Congressional Reconstruction, which began in 1867, federal officials oversaw the registration of eligible Alabama voters ahead of statewide elections. Those voters included, for the first time, African American men, who were registered alongside white men as free citizens of the state.

Efforts to control voting access were frequent, through various means including manipulation, intimidation and violence. This simple ballot box from Perote, Bullock County, is a reminder of a time in Alabama’s history when voting was an act of courage and a symbol of hard-won freedoms.

Textile Loom

A hulking piece of machinery helps visitors understand the scale of the industrial era. Textile manufacturing is one of Alabama’s oldest industries. By the turn of the 20th century, towns like Huntsville, Opelika and Sylacauga were major cotton mill centers.

In the 1930s, the Draper Corporation built this textile loom for the West Point Manufacturing Company, which operated several cotton mills in east Alabama. Before its acquisition for Alabama Voices, the loom was preserved in Langdale Mill by the City of Valley.

Civil War flag

Members of the Young Men’s Secession Association of Mobile were presented with this flag on Dec. 18, 1860, two days after South Carolina seceded from the Union. On Jan. 5, 1861, Alabama volunteers under this flag captured Fort Morgan from Union control. The following week, delegates gathered in Montgomery and voted to secede. The flag flew above Fort Morgan until March 13, 1861.

Curators swap out the Civil War flags displayed in Alabama Voices on a regular basis. The ADAH has one of the largest collections of Civil War flags in the country and a robust, privately funded conservation program. Since 1991, 28 flags have been conserved at a cost of more than $350,000. The banner of the Young Men’s Secession Association was conserved in 2009 at a cost of nearly $21,000.

B-24 Propeller

After the United States entered World War II in December 1941, government, industry and private citizens mobilized in support of victory. Approximately 300,000 Alabamians donned service uniforms during the war. More than 6,000 lost their lives.

In Alabama, military bases expanded, and new ones appeared. Many of its shipyards, ordnance works, coal mines, iron furnaces, lumber mills and textile mills adapted to serve new wartime purposes. Four-engine B-24 Liberators were flown to Alabama for alterations at the Bechtel-McCone-Parsons Birmingham Modification Center before deployment overseas.

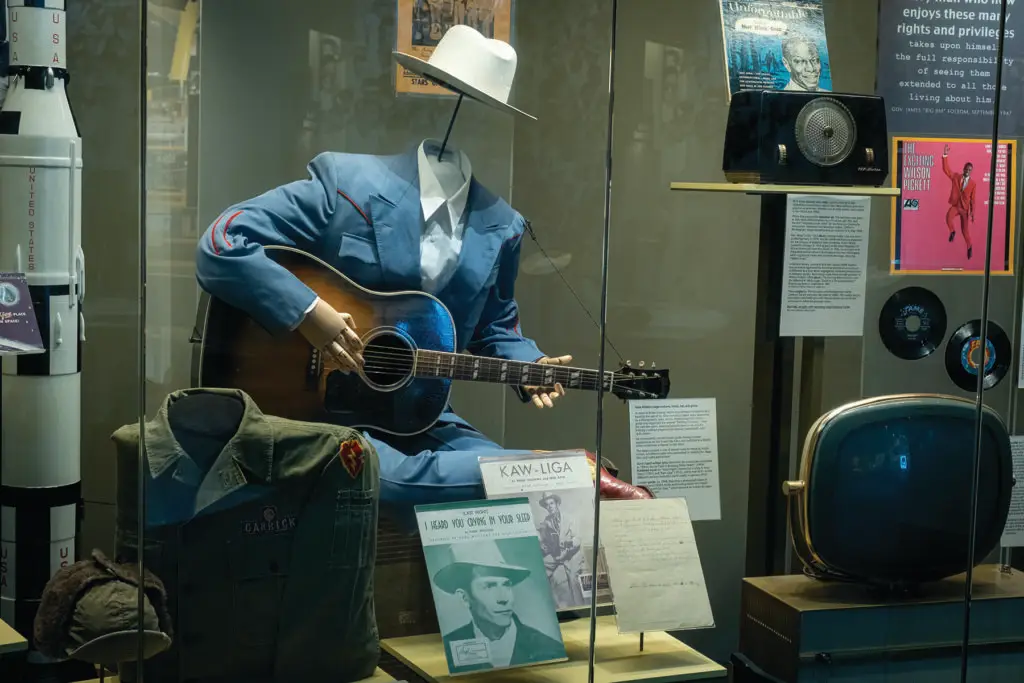

Hank Williams Suit

Nudie Cohn didn’t make suits for just anyone. The Ukrainian-born tailor, who arrived in America at the age of 11, was known for his elaborate, colorful costuming of rodeo performers, actors and radio stars. A “Nudie Suit” was a flashy, sequined status symbol.

Hank Williams’ “Nudie Suit” on display in Alabama Voices is conservative by Cohn’s standards. Still, the rich layers of the Butler County crooner abound in the exhibit case. It features the Gibson guitar he played early in his career, including some of his first appearances on the Grand Ole Opry, as well as posters and sheet music. Handwritten lyrics to the 1949 song “When You’re Tired of Breaking Other Hearts” includes a mournful reminder that the hillbilly Shakespeare’s time on earth was tragically short. “This is Hank’s own hand writing” reads a note at the bottom. The authentication was written by his mother, Jessie Skipper, after Williams died in January 1953 at the age of 29.

Harper Lee’s Medal of Freedom

In 2007, President George W. Bush presented Alabama author Nelle Harper Lee with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest award given to a civilian by a president. To Kill a Mockingbird had “influenced the character of our country for the better,” President Bush said. He called the novel “a gift to the entire world.” A bestseller since its 1960 release, the book was awarded the 1961 Pulitzer Prize and adapted into an award-winning film. Lee’s literary triumph has been translated into more than 40 languages.

Robertson camera

Montgomery photographer Paul Robertson witnessed history through the lens of his camera. Robertson’s photographs of civil rights protests appeared in major newspapers and magazines across the United States.

In 1956, Robertson snapped an image of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. having his booking photograph taken after an arrest during the pivotal Montgomery Bus Boycott, the event which launched a decade-long period when African Americans carried out a succession of protests to claim their rights as citizens.

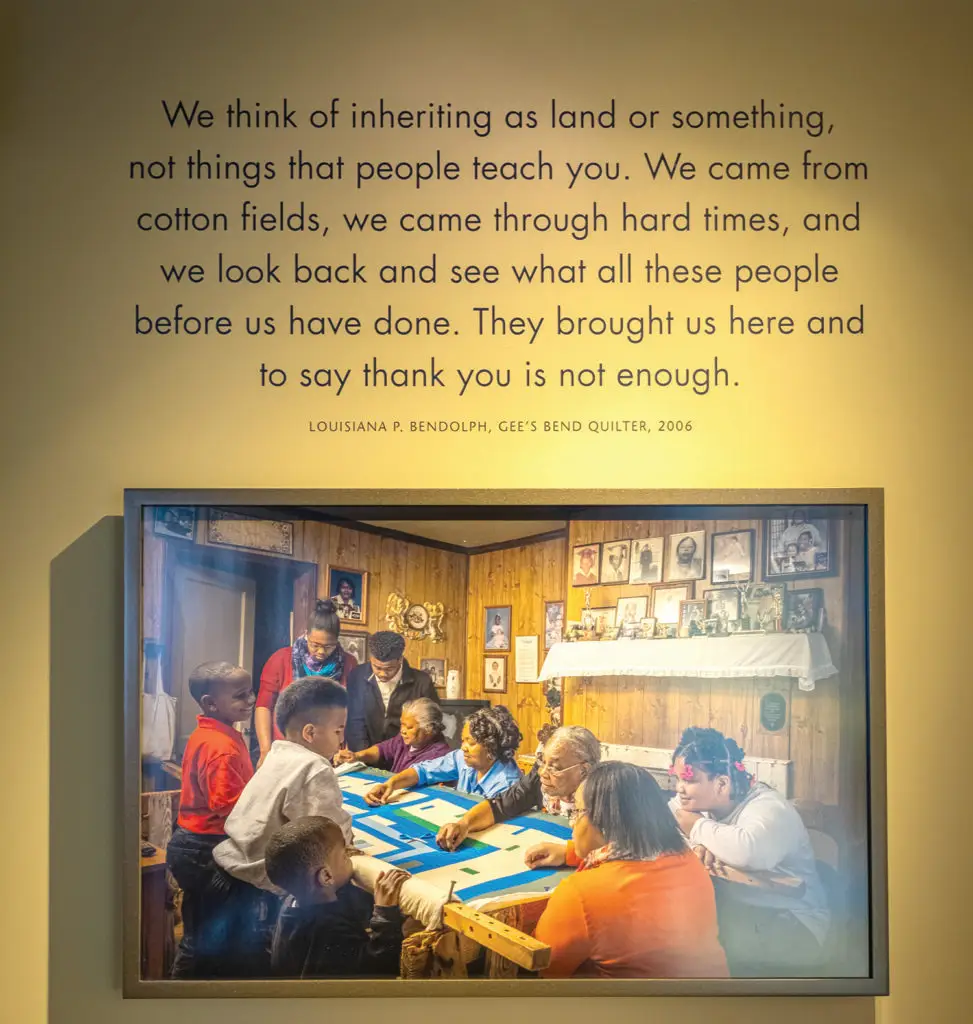

Bendolph quilting photograph

One of the final images in the exhibit is a photograph of Gee’s Bend quilter Louisiana P. Bendolph, taken by Mark Gooch as a special commission by the ADAH called “Our Alabama.” Bendolph is seated in her family home, working on a quilt alongside other members of her family. The younger generations depicted are the inheritors of the Alabama quilting tradition that Bendolph and others received from their mothers and grandmothers.

What better way to conclude an exhibit chronicling 300 years of Alabama—and Alabamians—than with the idea that all of us, young and old, can be the inheritors of such rich history, such boundless promise.

Museum of Alabama

(Located on the second floor of the Alabama Department of Archives and History)

624 Washington Avenue, Montgomery, AL

archives.alabama.gov

Museum Hours: Monday – Saturday

8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Closed all state and federal holidays