By Pamela A. Keene

Imagine being forced to leave your homeland for an unknown place 900 miles away. That’s what happened 180 years ago when more than 17,000 Cherokee men, women and children living in the Southeast walked, rode boats, and boarded trains to their new home in Oklahoma.

Along the way, nearly 25 percent of the men, women and children died of disease, cold, hunger and hardship. The remaining Cherokee recreated the Cherokee Nation, which still thrives today as a sovereign nation with more than 330,000 citizens across the United States. It is based in Oklahoma.

“For centuries the Cherokees lived on and hunted the lands in what is now Kentucky, parts of Virginia, South Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, and North Carolina,” says Troy Wayne Poteete, executive director of the Oklahoma-based National Trail of Tears Association. “As the European settlers moved in, the Cherokees assimilated into the settlers’ way of life; their lands shrank, and they adapted to an agricultural lifestyle and left their hunting ways behind.”

By the 1790s, Revolutionary American leadership negotiated treaties with the Cherokees, each time taking more land for the white settlers. Some Cherokees voluntarily left their land to move west. Talk of relocation began and by 1830, the U.S. government had passed the Indian Removal Act. Over several years, the Supreme Court heard two cases about the removal.

Some Cherokees willingly moved west, but about 75 percent remained, split between moving to preserve their nation’s identity or remaining on their native homeland.

By this time, Cherokees living in northern Alabama had become part of the sovereign Cherokee Nation, which was then headquartered in New Echota, Ga. By 1835, a splinter group of Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota that, although signed by a minority of Cherokee leadership, forced the Cherokees to give up their native lands and move to 160,000 acres in Oklahoma.

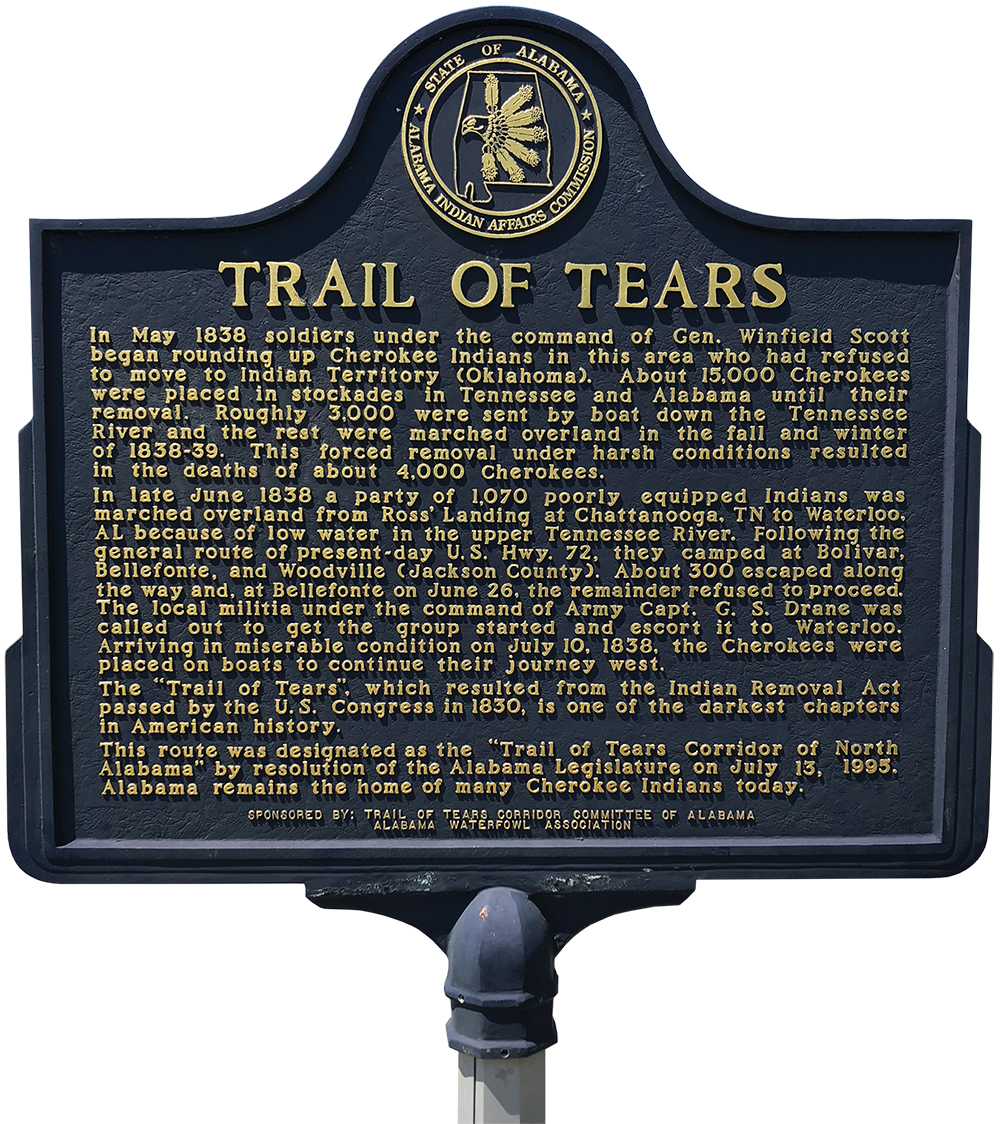

Three years later the federal government began the forced removal of the Cherokees on what has now become known as the Trail of Tears. Many Cherokees were rounded up and imprisoned in forts and camps before they began the grueling journey westward to Oklahoma. Many lives were lost, but the Cherokee nation survived.

As Cherokees across the country commemorate the 180th Trail of Tears, Poteete makes it clear why it should be remembered.

“We participate in the commemoration of that sad episode because it affords us the opportunity to honor the resilience, the tenacity, and the perseverance of that generation who refused to be defeated,” Poteete says. “We certainly don’t do it because we wish to somehow appropriate their victimization to ourselves. We personally didn’t endure the Trail of Tears and no one alive today had anything to do with that tragedy.”

Alabama’s connections

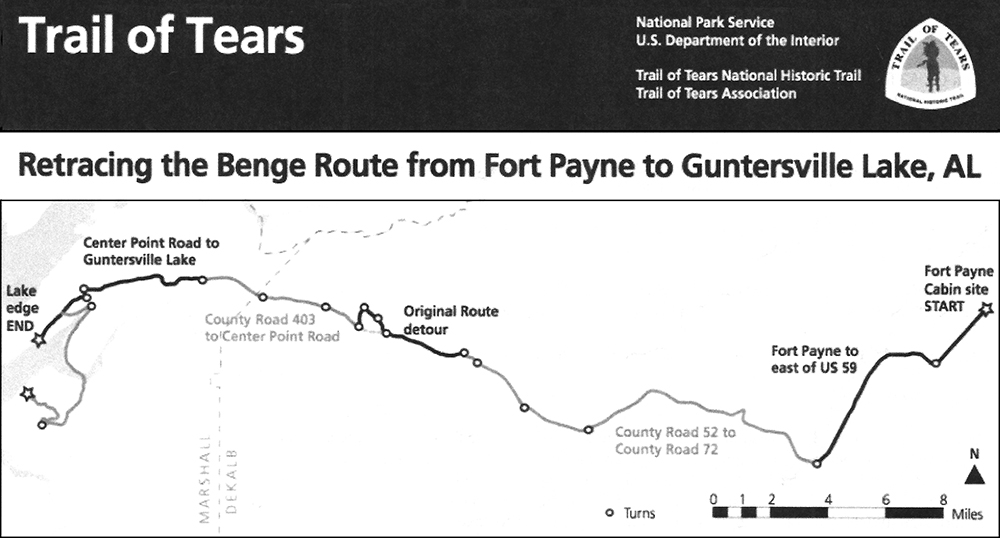

Many sites in Alabama factored into the removal on the Trail of Tears. The Cherokees were rounded up and detained in places like Fort Payne, or across the state lines at Chattanooga. Five known routes crossed north Alabama and took the Cherokee from their homeland on foot, by boat and train through towns like Guntersville, Tuscumbia, Decatur, Huntsville and Waterloo.

Several of these towns have historic markers, memorials, visitor and interpretive centers, monuments and remnants of witness buildings, which existed when the Trail of Tears took place. State and federal parks help preserve the history.

Shannon Keith is president of the Alabama chapter of the Trail of Tears Association and a member of the Trail of Tears National Board of Directors. “Alabama factored significantly in the lives of the Cherokees and the Trail of Tears,” she says.

“And our state has been very supportive of our work to commemorate this part of our history. In fact, our annual meeting of the Trail of Tears National Association is taking place in Decatur in October. It is an official event of Alabama’ s bicentennial and the National Park Service celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the National Trails System. It will be a chance to again draw attention to the Trail of Tears and the tribes that were removed.”

Commemoration events

Alabamians have recognized the story of the Trail of Tears with several events:

- 23rd Annual Trail of Tears National Annual Conference and Symposium (www.nationaltota.com), will be Oct. 26-28 in various locations in Decatur. Several events in this conference are open to the public, including guided walking tours of Decatur and significant sites related to the Trail of Tears on Friday, Oct. 26, and a concert by playwright and country-Western singer-songwriter and member of the Cherokee Nation Becky Hobbs on Saturday, Oct. 27. There will be workshops about genealogy and Cherokee history, and the group will also tour the Tuscumbia Landing preservation project

- The Trail of Tears Commemorative Motorcycle Ride gives participants a chance to see the Trail of Tears, to learn about its history and legacy and to travel across the state on one of the same routes that the Cherokees walked toward their new homeland. It routinely attracts upwards of 15,000 motorcyclists. This year’s 25th anniversary one-day event was Sept. 15; it began in Bridgeport and ended in Waterloo. al-tn-trailoftears.net

- Oka Kapassa, The Return to Cold Water Festival, took place in September in Tuscumbia’s Spring Park. A gathering of representatives of Native American Tribes, the festival celebrates the kindness shown to them by the citizens of Tuscumbia during the Indian Removal.

“The residents of Tuscumbia were the documented only people who offered assistance back then to the Native Americans on the Trail of Tears,” says Terry McGee, chairman of the Oka Kapassa Festival. “They brought food, blankets and other supplies to make sure they were well taken care of.” This year’s festival featured a school day with hands-on activities for students. Saturday offered a showcase of native music and dance, native craft artisans, storytelling and Chickasaw, Choctaw and Cherokee foods. (256) 383-0783 or visit okakapassa.org

Places to visit in Alabama to learn more about the Trail of Tears.

A sampling of historic sites around the state that are open to the public

Decatur: Numerous historical markers dot the landscape of Decatur and mark significant events of the Trail of Tears. Located on the Tennessee River, Decatur factored heavily in the Trail of Tears. This is where many Cherokees transitioned from boat to train to journey farther west. Rhodes Ferry Park includes a wayside exhibit that tells the story of this part of the Trail of Tears. (256) 341-4930 or visit decaturparks.com

Decatur: Numerous historical markers dot the landscape of Decatur and mark significant events of the Trail of Tears. Located on the Tennessee River, Decatur factored heavily in the Trail of Tears. This is where many Cherokees transitioned from boat to train to journey farther west. Rhodes Ferry Park includes a wayside exhibit that tells the story of this part of the Trail of Tears. (256) 341-4930 or visit decaturparks.com

Willstown Mission Cemetery, Fort Payne: The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions agreed to open a mission and school in Willstown in 1823. Only a few of the graves there have been identified. Two historical markers tell the story of the school, the cemetery and the importance to the Cherokee. (256) 845-6888 or visitlandmarksdekalbal.org/articles/WillstownCemetery.html

Willstown Mission Cemetery, Fort Payne: The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions agreed to open a mission and school in Willstown in 1823. Only a few of the graves there have been identified. Two historical markers tell the story of the school, the cemetery and the importance to the Cherokee. (256) 845-6888 or visitlandmarksdekalbal.org/articles/WillstownCemetery.html

Waterloo Landing: At the end of a 230-mile evacuation walk over land through North Alabama, Cherokees were transferred to the steamboat Smelter to follow a water trail to their new homeland. (256) 764-3237.

Tuscumbia Landing, Sheffield: Archeological digs since 2007 have revealed a railroad bed and other remnants of the Trail of Tears, the Civil War and bomb factories used in World War I. The site is being commercially developed with the intent of preserving history and protecting the environment. Plans are to open a Native American Visitors’ Center there in the next several years. The site is fenced, so direct access is not permitted. However, visitors can view the location. (256) 383-0250 or visit tuscumbialanding.org

Tuscumbia Landing, Sheffield: Archeological digs since 2007 have revealed a railroad bed and other remnants of the Trail of Tears, the Civil War and bomb factories used in World War I. The site is being commercially developed with the intent of preserving history and protecting the environment. Plans are to open a Native American Visitors’ Center there in the next several years. The site is fenced, so direct access is not permitted. However, visitors can view the location. (256) 383-0250 or visit tuscumbialanding.org

Fort Payne Cabin: The cabin, once owned by Cherokee John Huss, was overtaken by the military that were stationed at Fort Payne to oversee the forced removal of the Cherokees in the mid-1830s. Only a chimney, the foundation and a stacked stone wall mark the site today. (256) 845-6888 or visit landmarksdekalbal.org/preserving-dekalb-county-alabama-landmarks/the-old-cabin-site

Fort Payne Cabin: The cabin, once owned by Cherokee John Huss, was overtaken by the military that were stationed at Fort Payne to oversee the forced removal of the Cherokees in the mid-1830s. Only a chimney, the foundation and a stacked stone wall mark the site today. (256) 845-6888 or visit landmarksdekalbal.org/preserving-dekalb-county-alabama-landmarks/the-old-cabin-site