New novel tells an exciting version of how we came to receive electricity in our homes

By Paul Wesslund

What if Thomas Edison was a bad guy? An evil genius? A man so desperate to protect his inventions that he would bribe the police and even electrocute dogs to show his electric systems were better than his competitors?

You’d have what writers like me have always been searching for—a dramatic, can’t-put-it-down story about electricity.

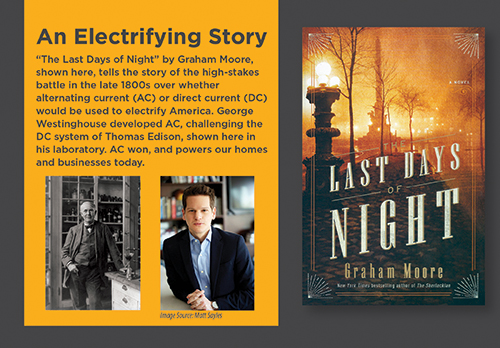

Graham Moore’s new novel The Last Days of Night tells the based-on-fact story of the ultra-high stakes battle between Edison and George Westinghouse over nothing less than what kind of electricity would power the U.S.

As with any good novel, it’s also about more than just the basic plot—it’s about invention and the creative process. It’s about the business, scheming, teamwork and luck that can make the difference between a genius who lives his life undiscovered and unknown, and one who enjoys wealth and fame.

Oscar-winning author

The storytelling moves briskly through courtroom drama, corporate intrigue, romance, greed and political corruption. It’s a history lesson, with a cast of famous characters, including the Wall Street baron J.P. Morgan, Alexander Graham Bell and eccentric inventor Nikola Tesla. The book includes an author’s note at the end to help separate fact from fiction. If it was a movie (and a movie is in the planning stages) it would be rated PG—a graphic description of the use of the electric chair plays a role, though the account was taken from actual newspaper reports of the day.

The storytelling moves briskly through courtroom drama, corporate intrigue, romance, greed and political corruption. It’s a history lesson, with a cast of famous characters, including the Wall Street baron J.P. Morgan, Alexander Graham Bell and eccentric inventor Nikola Tesla. The book includes an author’s note at the end to help separate fact from fiction. If it was a movie (and a movie is in the planning stages) it would be rated PG—a graphic description of the use of the electric chair plays a role, though the account was taken from actual newspaper reports of the day.

Moore is most popularly known as the Oscar-winning screenwriter for the 2014 movie “The Imitation Game” about WWII codebreakers. The Last Days of Night tells its story through the character of Paul Cravath, the smart but inexperienced attorney Westinghouse hired to fight the scores of lawsuits Edison had filed against him.

In the late 1800s, Edison was turning his invention of the light bulb into a network for electrifying the country, starting in New York City. The Westinghouse company had invented what it felt was a better light bulb, but the lawsuits claimed it was just a copy of Edison’s.

The much bigger issue came with how the electricity would be delivered to those light bulbs. Edison’s system used direct current (DC), which is what comes out of any battery you have in your home. Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla had developed alternating current (AC), so named because it actually changes direction about 60 times a second, as a more efficient way to deliver electricity over long distances. Alternating current won—AC is the kind of electricity found in your home today.

Fear of electricity

A feature of the fight was a media relations war over whether AC or DC was more dangerous. In those early days of electricity, it created both fear and amazement since few people understood the phenomenon. In the 1930s, 40 years after the events in this book, electricity started coming to rural parts of our country. And some of those same fears came with it. One story told of a man who wanted to make sure a bulb stayed screwed into the overhead socket so the electricity wouldn’t flow out and electrocute everyone in the room.

In the book, Moore covers the complexities of generating and delivering electricity—but he does so with a sense of excitement. The great gift to Moore was that his unlikely and compelling character, attorney Paul Cravath, was a real person. And he had a real romance with a real celebrity, who happened to have her own creative genius, backed by a cleverness for self-promotion and a willingness to cut ethical corners.

The story ends on an intelligently positive note, making the point that invention and creation require a cast of talents. The book concludes with a tribute to all of the characters: “Only together could they have birthed the system that was now the bone and sinew of these United States. No one man could have done it. In order to produce such a wonder … the world required … Visionaries like Tesla. Craftsmen like Westinghouse. Salesmen like Edison.”

Paul Wesslund writes on cooperative issues for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, the Arlington, Va.-based service arm of the nation’s 900-plus consumer-owned, not-for-profit electric cooperatives.