Alabama athletes give back to causes close to home

By Tim Gayle

It took a 15-year prison term for Sherman Williams to finally understand his lifestyle wasn’t working.

About the same time, he came to the realization that if his life were to have any meaning, he needed to talk to children from the same impoverished background and reach them before they started down the self-destructive path he took at their age.

That’s why he teamed up with his college roommate at Alabama, former NFL star David Palmer, to start a foundation to help children learn to say no to the vices surrounding them and focus on more important things, such as family and education.

“Both of us have mirror-image backgrounds,” says Williams, who won a Super Bowl ring with the Dallas Cowboys. “We just wanted to make sure we put kids in the proper frame of mind and not have to go through some of the same things we went through. We try to give them some testimony about our experiences so they can have a role model to tell them what things can happen to you if you make bad choices.”

It’s a common theme among players who reach the professional level: Earning a celebrity status allows them to give back to their communities. Often, they give back in a manner that is reflective of their own background.

There’s New Orleans Saints running back Mark Ingram, who won the Heisman at Alabama while his father, former New York Giants receiver Mark Ingram Sr., was serving time in prison. The Mark Ingram Foundation helps children whose parents are incarcerated.

Or former Auburn football star Kendall Simmons, who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes soon after he was drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers and now calls Alabama home. He sponsors an annual “Swing4Diabetes” charity golf tournament and speaks to children who have diabetes.

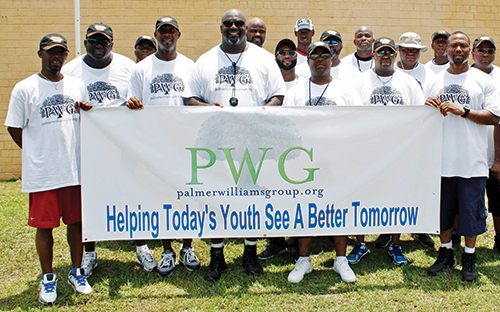

photo courtesy River Region Sports

A position of influence

“When I got into the NFL, I started talking to other guys that I was close to on the team,” said Montgomery’s Antoine Caldwell, a former lineman at Alabama and with the Houston Texans. Caldwell continues to team up with Tennessee Titans safety Rashad Johnson and former Alabama teammate B.J. Stabler in their For the Family Foundation. “I was looking at guys who were doing things in their own communities and back home and it seemed like a lot of those guys were doing things involving the kids. It’s something I already felt was important to do, but once I got their advice on it, it just made perfect sense.

“You’re in a position where you have some influence, you have a platform. And when you have that, what’s a better time to give back to the kids? That’s when they’re going to be the most attentive and listening to what you’re saying.”

Johnson, who runs his own Walk-on to Champions Foundation, continues to put on a free football clinic every year in his hometown of Sulligent, relying on Caldwell, Stabler and other college and professional teammates as instructors.

Not long ago, Roman Harper put on events in his hometown of Prattville. But the former New Orleans Saints safety, who is now with the Carolina Panthers, learned a lesson much like the one learned by current teammate and former Auburn quarterback Cam Newton, an Atlanta native: While the state of Alabama worships Alabama and Auburn stars, a professional athlete can raise more money in the hometown of his professional franchise.

Harper’s mother Princess, who runs Harper’s Hope 4*1 Foundation (a play on Harper’s jersey number, 41), says a foundation is a method of protecting the player’s income while allowing him to raise money for worthy causes. For example, Harper’s “41 Days of Hope” targets needy families in the 41 days leading up to Christmas, both in Alabama and in the Charlotte area.

“The foundation was my idea because I knew it was a way to help people,” she says. “We talked about the foundation when he won the Super Bowl (with the Saints in 2009) because, you know, he was a hot commodity at the time and now we can get support behind us and help the community.”

But while a professional athlete has his highest visibility in his franchise’s backyard, it strikes a deeper chord to help young people in their respective hometowns.

Former Auburn baseball stars Tim Hudson and Josh Donaldson, for example, have provided financial support and volunteered their time for their high schools, Glenwood School in Phenix City and Faith Academy in Mobile, respectively. Williams, the former Alabama star, coaches a 6-and-under youth football league team in his hometown of Prichard.

Having an example

Reggie Barlow, the former Alabama State University player and coach who spent eight years in the National Football League, often ventures back to his childhood haunts to serve as a role model in economically depressed neighborhoods.

“There are different ways to give back,” says Barlow. “A lot of times, it isn’t about giving money; sometimes, it’s just being present there and sharing conversation with some of the people who typically wouldn’t be able to talk to a former NFL player.”

Barlow said his introduction to the National Football League included a speech by the Jacksonville Jaguars’ head coach, Tom Coughlin, about giving back to the community.

The Jaguars required players to give back. “I had ‘Barlow’s Buddies,’ where you selected kids who had shown improvement in the classroom over the course of the fall term and we’d bring them to the game and celebrate them. It’s almost like the saying, ‘To [whom] much is given, much is required.’”

For any professional athlete who has learned the value of teamwork, providing for the less fortunate is a logical path. Those who have the financial resources to do so organize contributions or services through their respective foundations. Hudson, the east Alabama native and World Series Champion pitcher, created the Hudson Family Foundation in 2009 to help children from financially struggling families.

But even players who aren’t multi-millionaires can still volunteer their time and contribute their knowledge. Barlow is now in his seventh year as a state spokesman for the National Football League’s Play 60 campaign, aimed at encouraging kids to be active for 60 minutes a day to combat childhood obesity.

“It’s really a good program to teach kids to be active. I enjoy doing it.”

Several athletes in this state have won national championships in college or participated in Super Bowls, the NBA Finals or the World Series. And while they wouldn’t trade those experiences for anything, putting a smile on a child’s face has a special meaning all its own.

“There’s nothing like it,” Caldwell says. “While I was out there coaching them up and talking to them, I visualized myself as that kid. That’s what made it so impactful. I know for those two hours I had those kids, that’s something they can always remember. Those types of memories and events will stick with them forever.”