Electric cooperatives and their consumer-members are joining together to invest in community solar installations, which generate clean, renewable electricity for their local communities.

Growth in electric cooperative interest in community solar skyrocketed in the past four years, says Tracy Warren, senior program manager with the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA).

“It’s clean, local and homegrown power,” she says. “The benefits stay within the community. There is just a lot to like.”

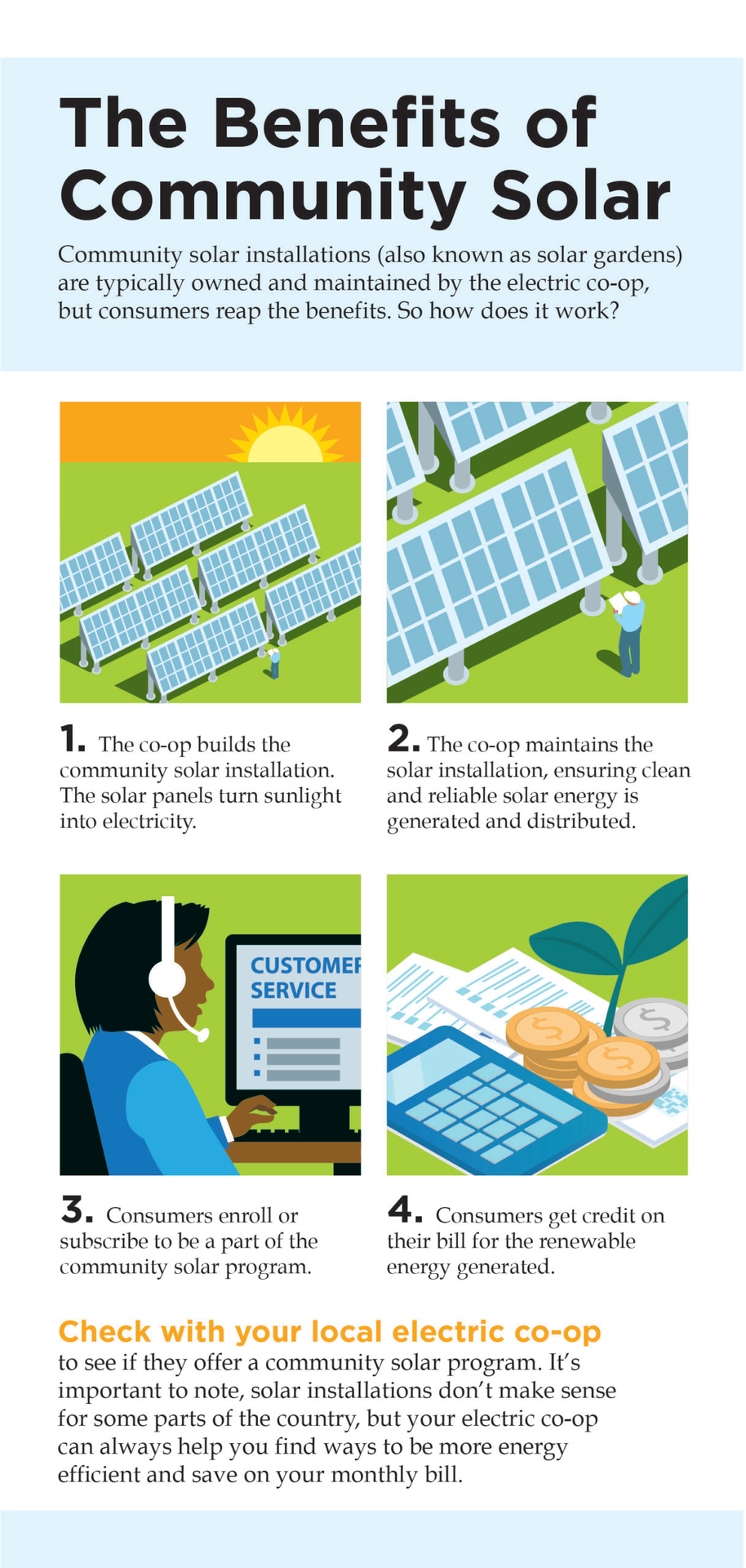

What makes community solar unique is not any special technology, but rather how it’s organized and financed. Basically, the electric co-op builds and operates an array of solar panels, then sells or leases the long-term energy output of the panels. In return, the home or business that participates typically receives credit on their electric bill for the portion of their power generated by those solar cells.

“It’s fun to see the community solar credit on your electric bill,” says Warren.

That fun helps drive the popularity of community solar for both electric co-ops and their consumer-members, says Warren. She coordinates online conferences about how to set up community solar programs that typically attract more than 250 people from co-ops around the country. A survey conducted four years ago found 38 electric co-ops had started a community solar project or were planning to. That number grew to 198 this year.

Community solar is not for everyone.

That number is still just a fraction of the more than 900 electric co-ops in the United States. Part of the reason for that small portion is that community solar is still developing. Another reason is that community solar might not make sense for some local electric co-ops, says Paul Carroll, a senior project manager for grant projects at NRECA.

“There’s not a one-size-fits-all anything,” says Carroll. He says some state laws restrict community solar-style setups. The co-op also needs to consider factors like solar power not being available when the sun doesn’t shine, the most practical fuels to generate electricity in that co-op’s area and what those fuels cost.

“A lot of co-ops already have plenty of wind and plenty of hydro,” says Carroll. “They’re always having to watch out for the best interests of their members. Expensive power is not what they’re about. They’re about the safest, most reliable, cheapest power possible. Solar has traditionally been a more expensive energy source.”

But that expense is changing fast. Costs for some of the major solar panel parts have fallen 85 percent in a seven-year period, says a report by NRECA, as technology improves and more mass production lowers prices.

“As you start making things at larger and larger scale, they just get cheaper,” says Carroll. “It’s the same as what happened with large-screen televisions. They used to be terribly expensive, $25,000, and now you can get a large-screen TV for 500 bucks.”

Co-ops are also smoothing the road to community solar with innovative financing and by sharing their practical experience with each other.

The National Rural Utilities Cooperative Finance Corporation, an organization that provides financing for electric co-ops, has developed a program that lets electric co-ops take advantage of tax incentives to build community solar systems. The organization also provides loans to support renewables and energy efficiency.

Community solar’s popularity has also been helped by a program that puts together information on solar energy, and shares that with other co-ops. That information can cover technical details from the most productive size of a solar power installation, to the best siting procedures in order to make sure the co-op complies with zoning and land use rules. That collaboration between the electric co-ops and the Department of Energy is called the SUNDA project, which stands for the descriptive but intimidating full name, Solar Utility Network Deployment Acceleration.

A new relationship with the co-op

NRECA’s Tracy Warren credits the SUNDA project with boosting community solar by finding, refining and promoting ideas from pioneering co-ops to others just thinking about trying it out.

Among the ideas catching on, she says, are financial arrangements that make a basic change to the structure of buying a share of the solar panels and then receiving credits. Instead, co-op members can lease part of the solar array, or even just pay for it month-to-month.

Community solar offers energy uniquely suited to local, member-owned electric co-ops, says Warren. A co-op can work with its members to decide how to tailor community solar to suit local conditions, or whether to offer it at all.

Among the advantages of community solar, says Warren, is that if an individual member doesn’t want to participate, they don’t have to. For members who do sign up, she says, “They feel like this is something they can do for future generations. They like the environmental benefits.” Some co-ops find a community solar program can help with economic development, as businesses look to locate in areas where they can meet the organization’s renewable energy goals.

“The community solar model is well-suited for co-ops because it is flexible, and it can be a way of matching supply with the demand from the co-op membership,” says Warren. “The co-op can gauge how interested its members are in participating and then size the program accordingly.”

Warren even sees community solar as building a stronger bond between the local co-op and its members.

“They’re literally helping to provide the power for the co-op,” she says. “That’s changing the relationship between the consumer-member and the co-op.”

Paul Wesslund writes on consumer and cooperative affairs for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, the national trade association representing more than 900 local electric cooperatives. From growing suburbs to remote farming communities, electric co-ops serve as engines of economic development for 42 million Americans across 56 percent of the nation’s landscape.