Artist’s murals preserve a city’s history

By Allison Griffin

The small stroke of the paintbrush, not even an inch wide, is dwarfed by the massive mural on the large brick wall. But the artist, Wes Hardin, patiently continues to paint, stroke by stroke, layer upon layer, color upon color.

Slowly — this mural has been in the works for months — the scenes take shape, and the characters come to life. And well they should; the portraits in this mural are of people who actually lived in Andalusia, a small south Alabama town that now boasts more than half a dozen of Hardin’s murals.

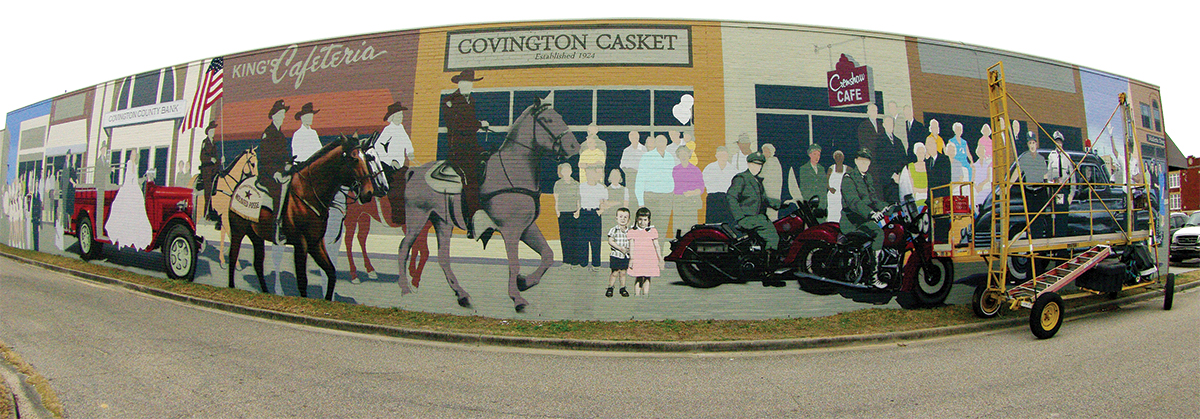

This mural is his, and Andalusia’s, most ambitious: 18 feet tall and 127 feet long, it’s a combination of seemingly disparate themes: a tribute to Covington County’s law enforcement, and a representation of some of the downtown’s long-ago businesses and storefronts. They’re tied together with a fictional parade, which was Hardin’s suggestion; it seemed like a good way to incorporate multiple, unrelated people in the same painting, and also to make the storefronts, which by themselves aren’t necessarily appealing visually, more interesting.

There are more than 60 faces in this mural, which have required a tremendous amount of planning, research and two full notebooks of photographic material that Hardin uses for reference. And the process of painting, with so much detail and so many faces, seems almost painstaking.

“It’s slow, because unlike the other pieces I do, I’ve got one or two subjects, and you just attack it,” Hardin says. “Here, I’ve got changes in colors and shade and distance. The dark color in the background’s not the same as the color in the foreground. There are so many different changes.”

See a video of Wes Hardin at work

His first commission was at a Panama City, Fla., community college, to paint the story of the English literature hall. After studying illustration and ad design at the Art Institute in south Florida, he continued to build a portfolio of work done on walls, buildings, on gym floors and in stadiums, working for private and corporate commissions as a freelance designer and illustrator.

He became creative director of an outdoor company in Dothan several years ago, and now continues to live and work there as a portrait artist and muralist. Dothan features several of Hardin’s impressive murals — a salute to Fort Rucker, one on Wiregrass contemporary music and a tribute to the oldest African Methodist Episcopal Church in the state.

Dothan was also how he came to Andalusia’s attention. Several years ago, retired Andalusia educator Pat Palmore and her husband and some friends vacationed in Vancouver, British Columbia. While traveling, the group saw signs advertising the city of Chemainus, which had become known as a “mural city.”

“It was just like an outdoor art gallery. It was just absolutely beautiful,” Palmore says. That small town needed to make a drastic change after the mill that employed many of its residents shut down; city leaders decided to turn the town into the mural capital of Canada. They commissioned artists from across North America and Europe to paint a series of murals.

At the time of the Palmores’ trip, the town reported having as many as half a million people to tour its murals. As a town on the route to the ski slopes, it had a natural traffic draw, and the city leaders capitalized on it.

“I thought, we just have to do murals in Andalusia, not only to show our history, but to make it beautiful like Chemainus,” Palmore said, perhaps also luring tourists to stop on their way to and from the Gulf Coast beaches. Others in Andalusia knew of Dothan’s murals, and learned about Hardin; he has also done eye-catching murals in Brewton, Colquitt, Ga. and Blakely, Ga.

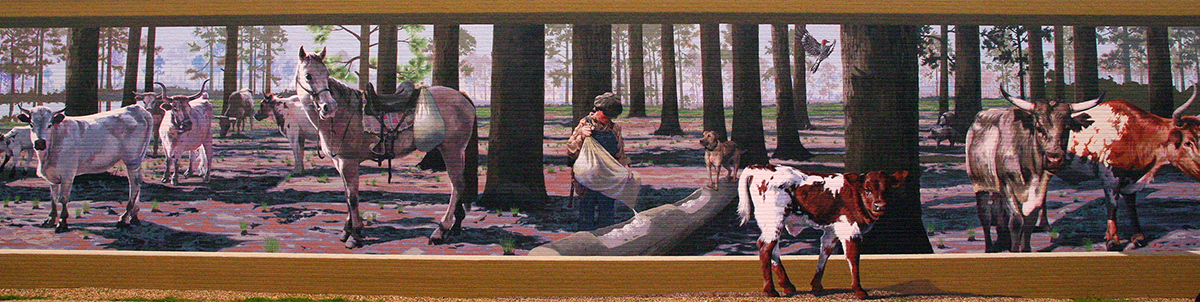

The city put together a murals committee, which Palmore helps to spearhead, and commissioned Hardin to do the first mural, which was the “Legends of Andalusia” on the side of a local radio station just off the court square. He has done several others, including a salute to Covington County’s early school days and a series dedicated to utilities, with one panel that depicts the early days of rural electrification.

The partnership has been beneficial for both Hardin and the city. The murals allowed Hardin, a full-time artist, to keep working through the lean years of the recent recession, and his work now helps the city draw tourists and sightseers. Andalusia, like most of the towns for which Hardin has done commissions, has to raise all the money for the murals, either through grants or private donations.

Palmore said Hardin, in addition to being a gifted artist, has been “absolutely delightful” to work with. “He wants to do everything to please us, and to get everything we want on the mural. He’s so good to help us.”

In whatever town he’s working, Hardin becomes a familiar sight to residents; most of his works take anywhere from 4-6 weeks to complete. (The parade mural, which he started last fall, is a notable exception, due to its size and complexity. Cold or wet weather also delays his work.)

Passers-by drop by frequently while he’s working, sometimes just to say “good job,” but sometimes they’re moved to park their cars and strike up a conversation.

During an interview and photo session with Alabama Living earlier this year, longtime Andalusia resident Jean Thomas stopped by. A portrait of her husband Don, now deceased, is one of several in the law enforcement tableau. Thomas felt that her husband’s portrait didn’t look like him, and told Hardin so; he had to reassure her that he was still in the working stage and that he would go back over the portrait about three times.

“He’ll look just like that picture,” Hardin said, pointing to an old photo he was using as a reference. “Is that going to be OK?”

Reassured, Thomas said yes, complimented him on his work and talked a little about her late husband, who was a game warden for more than 25 years. Residents often stop and tell him their personal stories, as another woman did while Hardin worked on a portrait of a man named Pap Gantt.

“She started talking about him, so now, it will mean more to me to paint it, and have a sense of who he was,” Hardin said. He doesn’t consider it an intrusion at all, and good-naturedly talks with curious onlookers.

“We’ve had good response to this character in front here, who leads the parade, J.D. Shakespeare,” a well-known former police officer. “A boy he actually raised after his mother and father had passed (came by to see the painting), and he got tears in his eyes talking about Mr. Shakespeare and how he watched after him and made sure he was on the right path. So there’s great stories here.”

Having opinions about his work is a good thing, Hardin said, because it means they feel a sense of ownership of it.

“I’ve never had any vandalism. I can’t explain that, but people feel a certain pride, because it’s theirs. They’re very gracious and they thank me, but it’s theirs.”

[box color=”gray” size=”big”]

Cullman’s murals weather devastating tornado

By Allison Griffin

The tornado of April 27, 2011, cut a swath through downtown Cullman, irrevocably changing its landscape. The courthouse and nearby emergency management building took a direct hit, as did two school buildings, the First Baptist Church and numerous businesses.

“Our town was just a mess,” recalls Dot Gudger, past president of the Cullman County Historical Society.

Also damaged was one of Cullman’s downtown murals, a colorful homage to the town and its 1880s beginnings. The top right portion of the wall crumbled against the winds of the tornado. The decision was made to repair the damaged portion; the bricks have been replaced, and the building’s owner also added windows during a remodel, so its appearance is much different than it was originally.

But the town pulled together to rebuild after the storm, and its dozen murals, which include a tribute to the Cullman Electric Cooperative, still stand to help tell the story of the town’s history. And, much like the murals in other towns and small cities, they attract a number of tourists, Gudger said.

Such murals also help strengthen public-private partnerships, said Elliot Knight, visual arts program manager for the Alabama State Council on the Arts. In many cases, the buildings are privately owned, so permissions have to be secured for the murals.

“A building owner could get really excited about telling a particular part of that history, and it’s really a win for them, to bring more attention to their space and beautify their location, but also for the community as a whole to benefit,” Knight says.

Gudger says such partnerships were crucial in Cullman, where business owners agreed to let the artists paint on their exterior walls. But just as important were the talents of the painters — Jack Tupper, Bethany Kerr and Donald Walker, all local artists, did Cullman’s murals, in some cases for free. And local organizations made generous donations toward the murals’ creation.

“Cullman is the most giving town,” Gudger says.

[/box]