By Minnie Lamberth

In May 2013, when Gary Minnick was serving as a principal within the Shelby County School System, he had an opportunity to travel with an eight-person team to Reynoldsburg, Ohio, to see a high school the U.S. Department of Education identified as a demonstration site for innovative and personalized student learning.

High school students in Reynoldsburg can choose one of four college/career academies that align with clusters of careers important to the local economy. More importantly, they also reflect the student’s personal interest. A health sciences academy, for example, is geared around the overall theme of health sciences careers yet offers multiple pathways for students to prepare to go to work right out of high school or pursue degrees at community colleges or universities with a head start in their field of interest.

The trip to Reynoldsburg, Minnick says, “struck a chord in me and everything I believe about how education should work. We needed something to motivate students.”

As Minnick explained, if he can get students locked in to the idea that what they are studying is preparing them for what they want to do in life, they will stay in school. “The key for me is high school is all about motivation,” Minnick says.

Shortly after his visit to Reynoldsburg, Minnick took a step to make this vision a reality when he was named principal of Boaz High School, a member of Marshall-Dekalb EC. From his perspective, he saw a city system with one high school as an easier model to work within to establish career academies than a larger, multiple high school system. After he came on board in July, Minnick began a deliberate process to determine “where the school needed to go to help students get the most out of their education.”

He started with the school’s teachers. “My emphasis as a principal is, people support what they help create,” Minnick says. “We needed buy-in from everybody.”

Over the next seven or eight months, the school began moving in the direction of creating career academies. Teachers studied the data provided by Regional Workforce Development Councils related to what jobs would be available in this part of the state, and they devised their pathways based on that data. “We had a strategy. We wanted ours to be research-based,” Minnick says.

By spring of 2014, the school was ready to establish three career academies, and students would choose their preference from these three.

The BELLA Academy is focused on students interested in business, education, law and liberal arts programs. Within that academy, there are a number of pathways that students can pursue, ranging from business finance to performing arts. Students also have the option to take business or law pathways through dual enrollment with nearby Snead Community College.

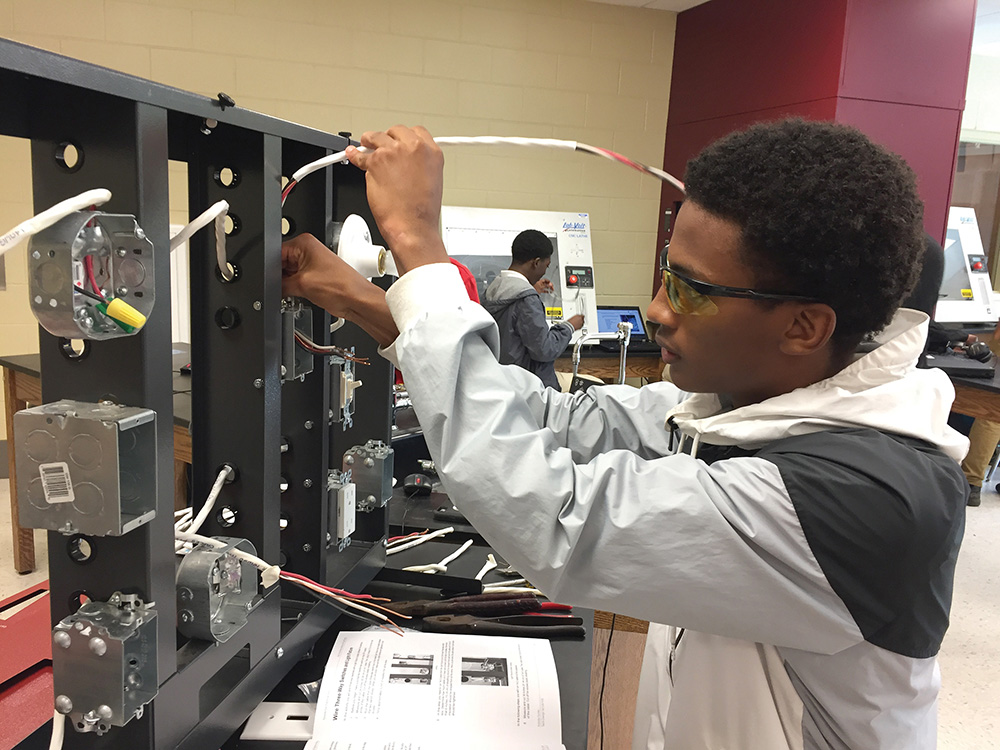

Within the H3 Academy, students can begin to prepare for high-demand careers in health sciences, human services, and the hospitality and tourism fields. Specific pathways within the academy range from culinary to sports medicine. The E-Stem Academy reflects the high-demand disciplines such as environmental science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Pathways include computer information science as well as environmental natural resources.

“We ended up with a dozen pathways on our campus,” Minnick says. However, if students don’t see what they want at Boaz High School, they can choose from eight career technical pathways at Marshall Technical School or explore dual enrollment with Snead State. In addition, Enterprise State Community College has a nearby satellite campus and offers programs.

Exposure to career academies begins in eighth grade through a preparatory course. “It’s designed for students to examine the career clusters and see the pathways that are available,” Minnick says. Students also tour the high school. “Our target is by the end of eighth grade, they and their parents will have decided which pathway they want to choose.” In the ninth grade, they enter the academy of their preference.

What if they change their mind later? “If they find out they don’t like a particular pathway in high school, I have done them a tremendous service,” Minnick says. Students and parents will have saved the thousands of dollars in tuition they would have paid in college to find out the same information. Regardless, they receive their high school diploma, and the educational preparation assists but doesn’t preclude the jobs or college plans they pursue.

The academies are still new enough that a class of students hasn’t completed the full five-year program, yet Minnick is pleased with the progress. “We’re asking our kids to take on higher challenges, and they’re accepting the challenge,” he says.

Farther south, the Mobile County Public School System (MCPSS) is an example of how a county system with multiple high schools has incorporated the academy concept to deliver education. “All 12 of our high schools are wall-to-wall academies. Every student must be in an academy,” says Larry Mouton, assistant superintendent of workforce development for MCPSS.

In Mobile, students begin the process in a ninth grade Freshman Academy, where they learn about the available academies. “For the next three years they take courses in their pathway,” Mouton says.

Each high school has multiple academies, but because they are designed and implemented by the school, not all high schools offer the same ones. However, if students are zoned to a school that doesn’t have the pathways they want, they can transfer to a school that does. In addition, internships are offered during the summer between junior and senior year that correlate with the student’s academy.

Among the aspects that make academies so successful, Mouton says, “It’s a way for business and industry to talk to students who have a shared interest.” In the past, if he told students an engineering firm was coming to school to talk to about engineering, hundreds who didn’t have an interest might come to hear the talk just to get out of class. At a school with an engineering academy, the firm can talk to students who have already expressed an interest.

“It gives business and industry a conduit to get into the classrooms and talk to the students and directly impact the workforce in our area,” Mouton says. As business and industry meet students and develop relationships, he adds, “this will facilitate their success when they graduate.”

Mobile County’s academies have been in place long enough to see improvement in student motivation. For example, at B.C. Rain High School, Mouton says, “When started five years ago, the graduation rate was somewhat over 50%. This year we anticipate they’ll hit a 90% graduation rate.”

As students see that they’re in a pathway to success, Mouton said they better understand the value of what they do in the classroom. “Our goal is to make sure every child has a pathway to a quality graduation,” Mouton says.