By Jim Plott

Listen.

That’s the sound of German soldiers marching in cadence.

But they are not heading off to battle. For these soldiers the war is over.

These weary, haggard, but still proud Germans are marching toward their new home for the duration of World War II – on U.S. soil.

Camp Aliceville in Pickens County stood as one of the largest prison camps in the U.S. during the war. At its height it housed 6,150 German prisoners, most of whom were part of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps.

While history might not replay itself, it can try to mirror it – although on a smaller scale. On May 3-4, the town of Aliceville, the camp’s location, will try to relive those wartime days on the home front.

The event will start Friday with a screening of a World War II movie and other features at the Aliceville Entertainment Complex. The old movie theater was donated to Aliceville Museum. The museum is home to what many say is the biggest display of German POW artifacts in the United States.

On Saturday re-enactments will be conducted. One re-enactment includes that day in early June 1943 when the town’s people turned out in curious masses to witness the first 500 German POWs being unloaded from Pullman train cars and marched more than a mile to the camp that for many was their home for the remainder of the war.

That day re-enactors will portray POW camp life and stage one of the few escape attempts from the now dismantled 800-acre prison camp that once was filled with more than 400 structures. Re-enactors will also stage a mock skirmish from the battle at El Alamein in North Africa where German forces surrendered to the British.

The event will be capped off with a USO Big Band Swing Dance and Dinner at Aliceville City Hall from 6 to 10 p.m. The Drew White Orchestra of Florence will be playing popular songs of the Big Band and WWII era. There is an admission.

“It’s a big day for Aliceville and the Aliceville Museum,” said John Gillum, executive director of the Aliceville Museum. “The first year that we did it, the museum experienced its biggest day in history in terms of visitors.”

Brien McWilliams, spearheading the re-enactment, emphasizes the importance of Aliceville and the war period in history.

“History, good and bad, needs to be remembered,” said McWilliams, who participates in numerous re-enactments including WWII-era battle scenes at the U.S.S. Alabama in Mobile and the Creek Indian attack at Fort Mims in Baldwin County. “I consider those Americans who were involved in World War II as our greatest generation and that history needs be kept alive.”

Why were they here?

In 1943, Allied forces defeated German and Italian armies in North Africa and captured 275,000 enemy soldiers. The U.S. military decided to move them to the United States, and the Army Corps of Engineers worked quickly to establish camps in nearly every state. By 1945, the nation was host to more than 500 camps with some 425,000 POWs.

Two sites in Alabama were chosen – near the town of Aliceville, and one near Opelika. Camp Aliceville became Alabama’s largest POW camp, with a capacity for 6,000 prisoners. Another smaller camp was constructed near Fort McClellan, and a fourth in what was then Fort Rucker.

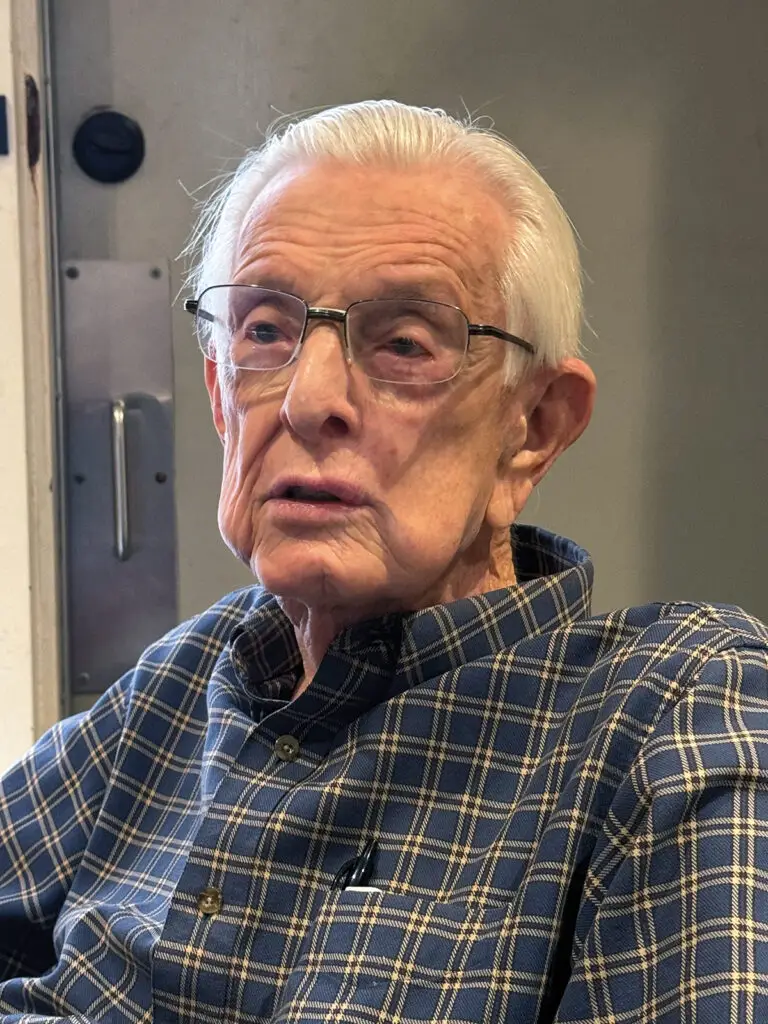

When the first Germans rolled in to Aliceville, P.M. “Pep” Johnston, now 93, had a front-row seat to the actual event. Johnston, then 12, and his family, like basically the entire population of Aliceville, disregarded appeals to stay home the day the Germans arrived.

“Most of us didn’t know what to expect since there had been so many rumors going around about who was to be housed in the camp,” Johnston recalls.

Johnston recalls people lining the main route from the depot to the camp while others took seats on porches, rooftops, on car hoods and the back of pickup trucks.

“(The Germans) had on the same dirty and soiled uniforms as we found out later from when they were captured in North Africa,” Johnston says. “They got off and formed platoons and marched toward the camp. Obviously, I did not know much about the military at the time, but I could tell they were well disciplined despite their condition.”

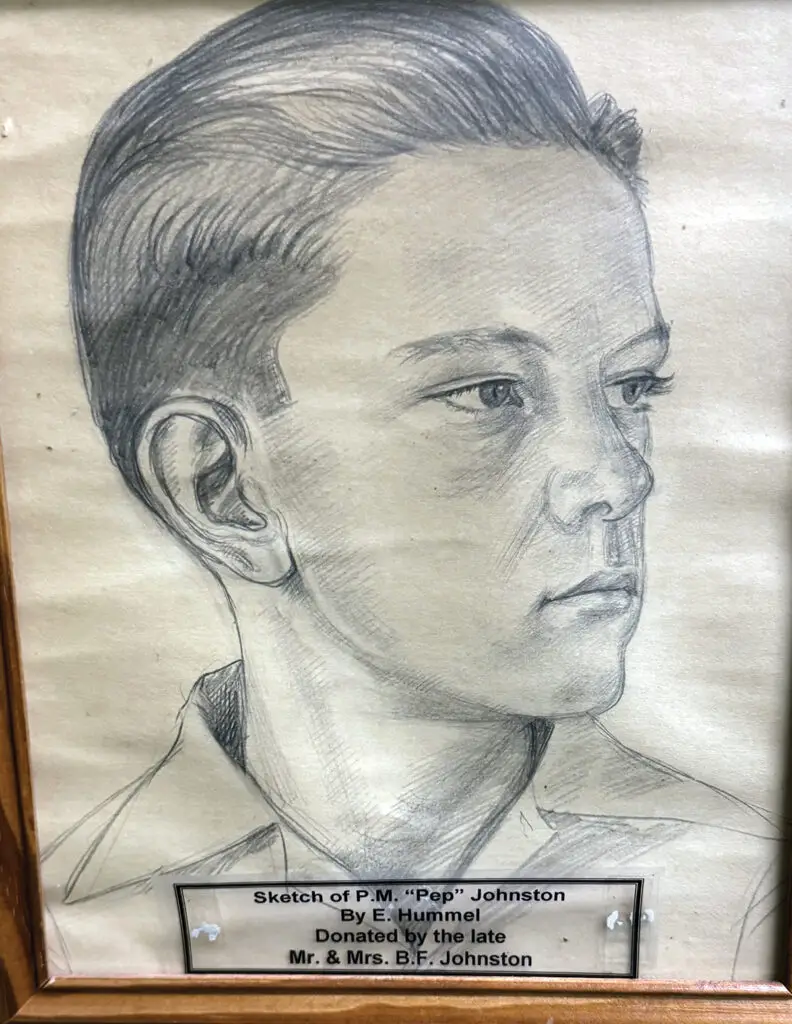

Johnston later got a closer glimpse of the POWs when several of them were employed at his father’s sawmill. One even did a drawing of the younger Johnston.

POW pampering

The camp was a comfortable home away from home for the German POWs. They settled into the camp and over time formed art and pottery classes, held theater and puppet productions and even formed several bands that performed at American officer functions. They also played sports and produced a camp newspaper from a printing press they bought in Jasper.

“There was a lot for them to do because you wanted them to stay busy rather than cause trouble. They could pretty much organize what they wanted to do within reason,” Gillum says. “In terms of quantity they ate better than most of the people in Aliceville, which was still coming out of the Great Depression. The thought was if we treat them good, the Germans would treat our guys being held in their prisons good. We now know that didn’t happen.”

The Germans also were served what no one in Aliceville could get – beer. That’s because Pickens County was a dry county so no alcohol could be sold, Gillum says.

After the war, the camp was dismantled, and the POWs were repatriated to their devastated homelands. In the decades after the war, a number of POWs returned to Alabama to reconnect with their past.

In the 1980s Sue Stabler, a longtime resident, issued a call to build a museum to commemorate Camp Aliceville. Residents and others began donating camp-related items, and over time even some former POWs began making contributions. The donation of the former Coca-Cola bottling plant building helped the museum grow.

Also in the 1980s and 1990s, the museum hosted several camp reunions involving camp guards and POWs, many of whom had formed close friendships. That ended when many Americans and Germans died or could no longer travel because of health.

Yet, Gillum said it is not uncommon for the children or grandchildren of the POWs to visit the museum.

“About 10 percent of our visitors every year come from Germany and a lot of times when they come, they bring items to donate that belonged to relatives who were POWs at the camp,” Gillum said. “Items from the camp keep showing up here whether they are from the Germans or relatives of Americans who were guards here. So, the museum keeps growing.”

Some information in this article is from the Encyclopedia of Alabama.