Weatherman Spann remains fascinated by the mysteries of weather

By Emmett Burnett

In the fall of 1962, in Greenville, Alabama’s W.O. Parmer Elementary School, teacher Edna Earle Porterfield commanded the attention of first-grade students – except for one. A 6-year-old boy opted instead to gaze out the window, observing cloud formations. Suddenly, the youngster was yanked from his chair by Ms. Porterfield for a hallway conference. He feared the worst.

But the teacher smiled and presented the window-gazing student with a library book. “I noticed you have been looking at clouds,” she told the youngster. “I thought you might like to know more about it.”

The boy was James Spann, and the incident refocused his life. More changes were to come.

When Spann was just 7, his father left the family, leaving a mother to raise her son. Young Spann and his mom moved to Tuscaloosa so she could attend the University of Alabama, earn a degree, and become a schoolteacher.

As a Tuscaloosa teen, Spann loved electronic equipment and earned a ham radio license. The Tuscaloosa High School principal allowed him and some friends to build a school radio station. “It was very illegal,” Spann chuckles. “We were supposed to have a broadcast range restricted to campus. But I embellished it. You could hear us in Northport.”

He turned a love of radio equipment into an interest in broadcasting. A local radio station, WTBC, called the school to ask if there was a student interested in working really bad hours for minimum wage. The school answered, “James Spann.”

Spann was hired. He later covered news, sports, and his soon to be specialty, weather. He also traveled to onsite weather occurrences. Many were terrible.

In 1974, his senior year, 80 people died of storm-related events. “I was at Peoples Hospital, in Jasper, Alabama, during a terrible tornado outbreak,” he recalls. “Many lives were lost. I saw things no 17-year-old should see.”

The dark side of weather taught lessons. Forecasting is more than predicting rainy days. Spann learned, “In this business, we must do everything we can to save lives. We try to use our platform to teach. The knowledge may help you on tornado and hurricane days.”

He adds, “I have always been fascinated by weather.” Spann references that childhood memory of gazing from his schoolroom window: “I would be looking out a window now if there was a window in this place.”

Working from everywhere

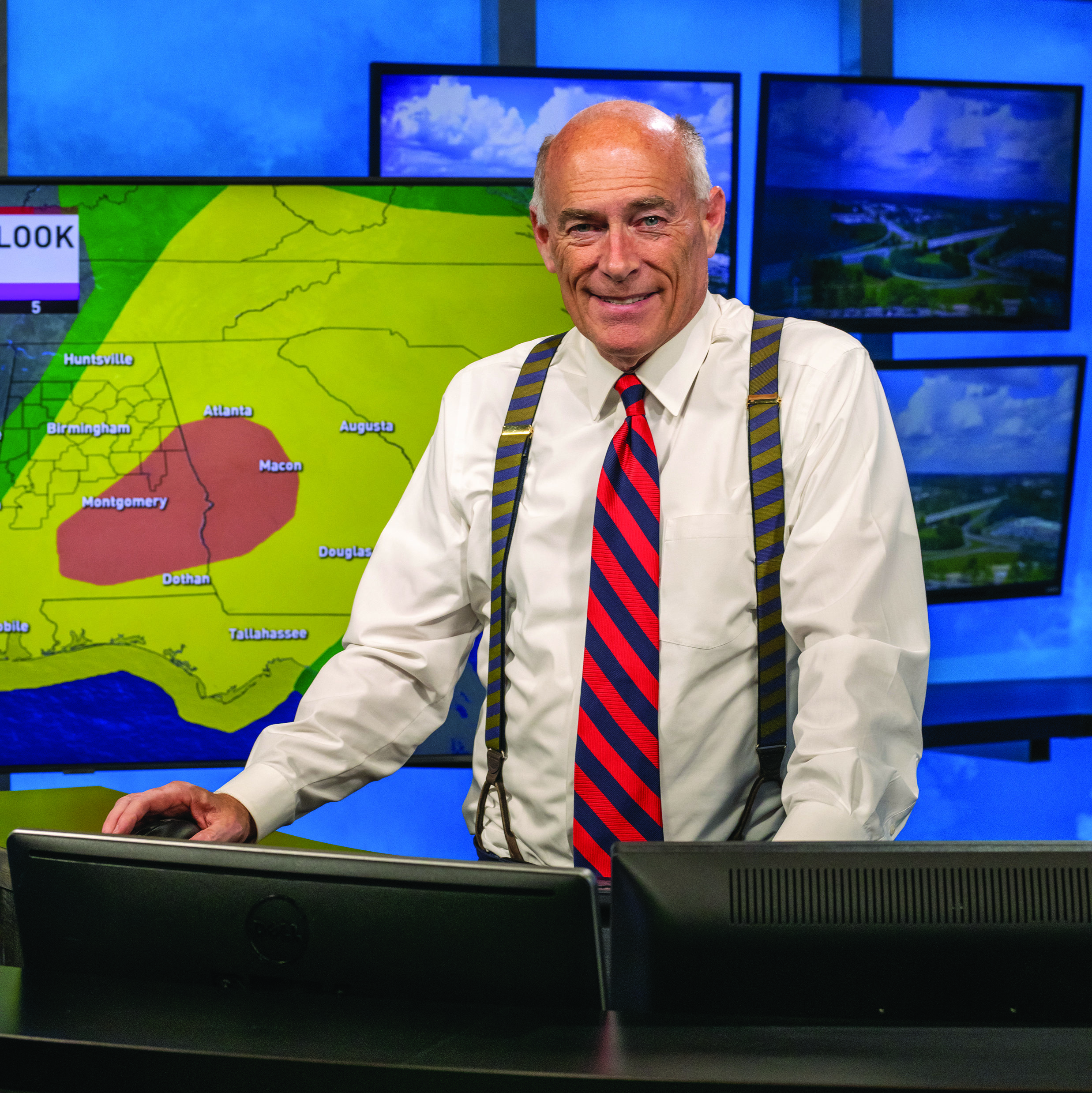

“This place” is WBMA – ABC 33/40 News and Weather Studio, Birmingham. Spann has worked from here for around 25 years. Actually, he works from everywhere.

He also has a TV studio in his home where he starts the day around 3:30 a.m., after getting a good night’s sleep of about two and half hours. From home his duties include gathering data, writing blog posts, producing “Weather Extreme” videos, and broadcasting weather reports to 24 radio stations across America.

There are also personal appearances to make. He is a frequent public speaker, including community events, charity drives, and elementary schools. Today he did all three before lunch.

Back at the studios of ABC 33/40, there is the local forecast to prepare. He will be on air at 4, 5, 6, and 10 p.m., or – and this is the exciting part – when breaking news dictates.

“We must be ready,” the meteorologist warns. “I monitor conditions across the state. If we are ripe for a tornado, we have got to be ready to go on air and fast. Time is of the essence and can literally be a life-or-death decision.”

He has no problem interrupting newscasts. Spann’s team can be on the air within 10 seconds when he shouts, “LET’S GO! NOW!”

At his control are live radar images, reconnaissance data, and 44 years of experience. He can examine aerial photographs of almost any Alabama city and identify buildings by name from memory.

“Lots of people don’t respond to radar,” he says. “They see colors like a bucket of spilled paint and shrug it off. If I say, ‘a tornado is 14 miles southwest of Clanton,’ nobody knows what that means. But if I warn, ‘a tornado is near Jim’s Pit Barbecue in Billingsley’ – everybody in Clanton knows where that is – they take action.”

He speaks with authority and hands-on training. In 1973, his junior year of high school, Spann was the first on scene when a tornado ripped through Brent, Alabama, killing five people. “That was my first experience with the violent side of weather,” he recalls. “I experienced the scent of death. You can take a shower, but that scent stays with you for three days.”

He was dispatched to Mobile for September 1979 Hurricane Frederic coverage. “We stayed at Azalea Middle School,” the veteran forecaster recalls. “The campus was an evacuation shelter for local nursing home patients to ride out the storm. We frantically moved the elderly to safer rooms that night when the roof blew off.”

He won an Emmy Award for covering a deadly tornado that ravaged Tuscaloosa on Dec. 16, 2000. The trunk of the wind funnel could encapsulate Bryant-Denny Stadium and it almost did.

He has dozens more such stories, remembering dates, damage, injuries, and death.

No shortage of weather events

Just as Alabama’s geography is diverse from mountains to beaches, so is its weather. “Typically, the more violent tornadoes, the F4s and F5, are more frequent in the northern part of the state,” he says. “South Alabama tornadoes are often short lived.” But all are dangerous.

“I have covered blizzards, floods, droughts, ice storms and heat waves from that green screen,” Spann adds, pointing at the most famous TV studio weather wall in Alabama.

The hardest Alabama weather phenomena to predict? Snow.

“We just don’t have enough recorded data to accurately predict snow because it doesn’t occur here that often,” he notes.

“School kids always ask me, ‘why can’t you get snow forecasts right?’ That’s a very good question,” the forecaster says with a smile.

But that is part of the fascination of weather. The meteorologist readily admits we do not know everything. Weather is still a mystery.

“When you’re young, you think you know it all,” says Spann, “but there is so much we do not know. I can’t tell you on a June morning where the thunderstorms will hit that afternoon. Weather is a challenge. It always will be.”

In non-weather-related activities, Spann is chairman of the board for Birmingham’s Grandview Medical Center. He is also children’s worship leader at Double Oak Community Church, Mt. Laurel campus in Birmingham. In addition, he enjoys working with youth sports.

He’s in his mid-60s but works out in a gym three days a week and plays tennis on Sundays with his family. Explaining his game, Spann notes, “We look really good on a tennis court – from a distance.”

He and wife Karen have been married over 40 years.

And Spann knows and remembers everybody. The photographer for this story, Jeff Rease, reminded Spann, “You coached my son in baseball!”

“Did he keep playing or did he stop?” Spann questioned. “Because he was good. He could have continued playing. I remember how good the team was but most of all, I remember the fun and camaraderie we had. I miss that.”

But back to the weather: “Looks like a calm day in Alabama,” the meteorologist says about today’s forecast. “Now tonight some thunderstorms are moving in. I will study it later from the closet.”

That’s right, his office is a closet, secluded and private. “This job requires critical thinking which for me requires privacy for concentration. My bosses have asked, ‘James, don’t you want a better office?’ I answer, nope.”

With the interview winding down, he conducts an impromptu tour of the studio as we walk out. In reflection he notes that Alabama weather forecasting is difficult at times.

“Meteorology is a game you cannot win but you try to stay in the game,” Spann says. “We don’t expect the audience to be total weather dweebs. That’s what we are.”

But he never forgets that giving accurate, reliable forecasts can save lives.

With that, the weatherman – in his crisp white shirt with trademark necktie and suspenders – returns to work. He scans weather data from electronic “windows,” just as he did from a Greenville elementary school windows many years ago.