By Katie Jackson

The word “folklife” often conjures images of old-school activities such as quilting, basket weaving, blacksmithing and square dancing. While folklife is certainly anchored in those and other age-old traditions, the term should also conjure images of the many vibrant, thoroughly modern traditions practiced by folks here in Alabama and beyond.

That’s the message the Alabama Folklife Association, a nonprofit established in 1980 to document, preserve and promote Alabama’s myriad folkways, is trying to spread throughout the state.

“Folklife” refers to a vast array of practices and traditions that families, communities and cultures around the world create and pass down through generations. Among them are arts and crafts, music and songs, dance, fashion, foods, skills, pastimes and religious practices.

Folklife is also a uniquely human concept — as Louis Armstrong once said, “all music is folk music; I ain’t never heard no horse sing a song.” And, according to AFA Executive Director Emily Blejwas, it’s one that all humans share because everyone has inherited at least one tradition from their culture, whether it’s a recipe, a story, or even a hobby such as fishing or hunting.

“Sometimes I worry that people think of folklife as preservation and resistance to change, as if there is only one true way of doing things,” Blejwas says. “That’s not it at all. Folklife has always been in a state of change — even the ‘old ways’ were in flux — and it’s constantly evolving.

“To me, folklife is bringing forward the traditions that define and empower us, in whatever ways they manifest and make sense for us,” she continues. “And because folklife exists in every community, it’s essential to elevate all of our folkways so that we’re always celebrating the abundance of Alabama.”

The AFA also believes these traditions are meant to be shared with others, which is why the AFA not only encourages folks to embrace their own cultures, but to share them across cultural lines.

“Even when they don’t spring from a person’s own culture, (these traditions) are things all Alabamians can take pride in,” Blejwas says.

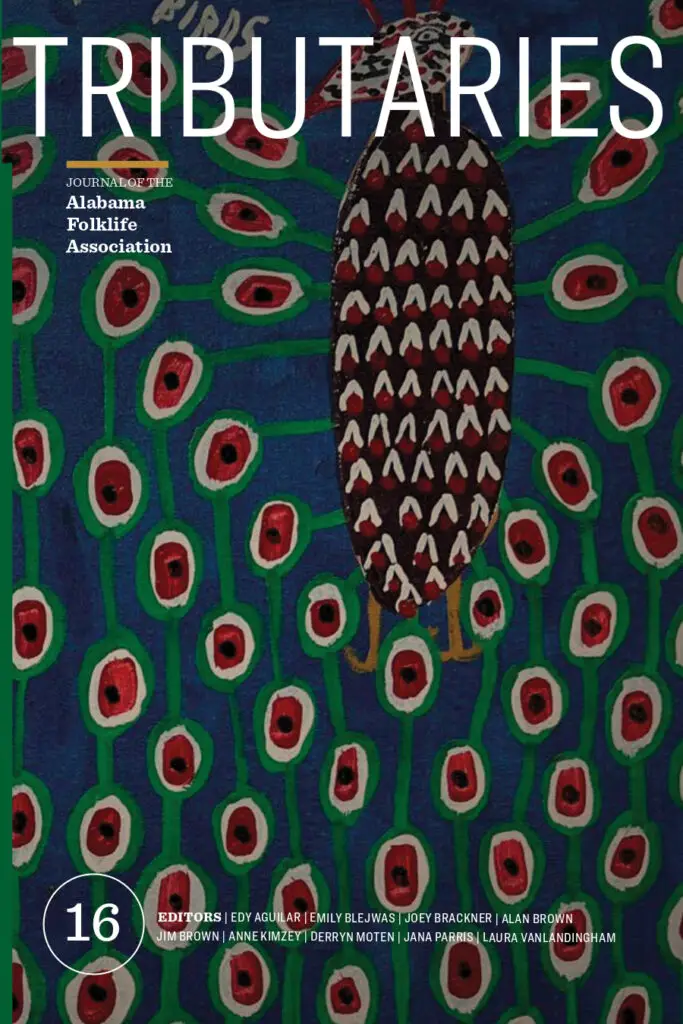

The AFA supports the state’s cultural richness through a wide variety of programs, including sponsoring presentations, workshops, events and training sessions that take folk traditions and knowledge into schools and communities. It also supports research and scholarship focused on past and present folkways and shares this information and the state’s folklife stories through venues such as its podcast, “Alabama Folk,” and its annual journal, Tributaries.

In addition, the AFA works closely with the Alabama State Council on the Arts and other state, regional and national arts and humanities organizations to provide grants and teaching programs for organizations and individuals wishing to share and further Alabama’s folk traditions.

These programs provide opportunities for current folk practitioners to share their knowledge and practices, but also help ensure new generations can discover them.

Working with young people

One way the AFA carries traditions forward is through its “Folk in Five” program, which introduces Alabama’s fourth graders, who are already taking a deep dive into state history and social studies, to the state’s folklife. Through the program, students have opportunities to see traditional artists at work, interview their own family and community members about their traditions and create five-minute videos to document what they have learned.

Potter Charles Smith, a Mobile artist known internationally for his detailed Afrocentric and ceremonial vessels, has relished the chance to share his work and his artistic journey with students.

Smith was in his late 40s before he fully realized that his work as a potter was a “calling” — “what I was born to do,” he says. But he first began to feel called to art in grade school, which is one reason he thinks fourth graders, who are innately curious, are an ideal audience. By meeting and interacting with a “living, breathing artist,” Smith hopes students will learn to appreciate their own cultures and maybe even find “callings” of their own that can be turned into careers.

“I want to break the mode of ‘starving artists,’” he says. “These kids need to know that there are so many disciplines in art, from creating art to museums to photography to computer design.”

Another artist who has shared her traditional art with students is Edy Aguilar of Huntsville. Born in Mexico, Aguilar came to the U.S. in 1997 at the age of 2 and grew up in Sylvania, Ala. Her mother, who had run a successful piñata-making business with Aguilar’s grandfather back in Mexico, began making and selling them in their adopted DeKalb County community.

“They started calling her ‘The Piñata Lady’ because everyone would call on her to make piñatas for every birthday party or special event,” Aguilar said.

Though she grew up helping her mother make those piñatas, Aguilar didn’t begin creating her own until after high school when Joan Reeves, a faculty member at Northeast Alabama Community College, encouraged her to embrace her Mexican heritage. Reeves also introduced her to Blejwas and the AFA, through which she learned about the ASCA Artist’s Apprenticeship grants. Aguilar applied for and received a grant that allowed her to pass her piñata tradition on to two young protégés.

Her involvement with the AFA has also broadened Aguilar’s own cultural boundaries as she has learned about other traditions such as basket weaving and cigar box guitars.

“Sharing cultures, especially in our country that is full of culture, brings people together and makes us feel a little bit more human,” she says. “If you really sit down with somebody you think is really different than you are and have a talk with them, you realize they are actually not much different. Everybody has traditions and cultures and sharing this tradition with someone else allows me to learn something about them.”

Sharing cultures is at the heart of everything Ester de Aguiar, executive director of Mobile’s International Festival, does. A native of Brazil, de Aguiar moved to Mobile at the age of 16 where she discovered a melting pot of cultures.

“A lot of people (from other countries and cultures) have made Mobile their home,” she says. Each culture has its own traditions — dance, art, food and more. Each year the festival, scheduled this year for Nov. 18, helps share the cultures of more than 70 countries and is also where de Aguiar has shared one of her own cultural treasures, brigadeiros.

Brigadeiros are iconic Brazilian truffle-like confections made with sweetened condensed milk and butter and traditionally flavored with cocoa or coconut and covered in sprinkles (though they can be made in any imaginable flavor). De Aguiar, who has been sharing them at the festival and beyond for years, sees them as much more than a delectable sweet.

“They are about promoting peace and friendship,” she says. “Food unites people. You feed people and they are going to love you. The more you share, the more you exchange with another human being, the more you open their mind and their heart.”

That openness resonates with de Aguiar who believes “we’re all the same, we are just diverse. Kind of like a garden that has lots of different kinds of plants in it, but it works.”

Centuries-old traditions

Sharing culture through a traditional art form is also important to David Ivey, a longtime AFA member and board member who is passionate about one of Alabama’s most beloved forms of folk music, Sacred Harp singing.

Described by Ivey as “the rock-and-roll of the colonial days,” Sacred Harp singing is performed a cappella, using only the human voice as a musical instrument. It’s a centuries-old tradition that originated in England before spreading to New England and then on to the South where it really took root. The songs, many of which come from The Sacred Harp hymnbook published in Georgia in 1844, use shapes rather than formal musical notations to guide singers.

This music is very much an Ivey family tradition, one David learned while growing up in Alabama’s Sand Mountain region surrounded by grandparents, parents, uncles and aunts who all sang or listened to Sacred Harp music. In fact, the Ivey family is renowned as one of Alabama’s premiere Sacred Harp singing families. In 2013, David was awarded an NEA National Heritage Fellowship, the highest American honor for a traditional artist.

For Ivey, the music is not just part of his tradition, but one anyone can embrace it because it is accessible to people of all singing skills and levels.

“Society and culture have taught people that they can’t sing unless they have a trained voice,” Ivey says. “But historically, humans have always sung, with or without training, and this form of music using shape notes is accessible to anyone. It lets us learn to sing with our ears.”

Ivey wants this musical tradition to carry on for generations to come and has promoted it throughout Alabama and across the globe as a singer, singing leader, organizer and conductor. He is also the recipient of numerous ASCA Artist’s Apprenticeship grants and is co-founder of Camp Fasola, a summer singing school open to all ages, held in Anniston and also in Poland.

Supporting the Sacred Harp art form and the artists who perform it matters deeply to Ivey. “To me, that’s at the core of enabling those traditions to be furthered, spread and taught and extended in time,” he says.

These four artists represent a just a tiny slice of Alabama’s diverse folklife that spans the state’s complex human, geographic, environmental, political, cultural and historic landscape. Whether it’s Vietnamese lion dancing or Poarch Creek shell carving, traditional quilting or old-time fiddling, pine needle basketry or herbal remedies, duck decoys or Jewish culture, the AFA is ready and eager to share it with the state and help pass on traditions for generations to come.

“We’re always looking for new artists, tradition bearers and makers,” Blejwas says.

To learn more about the state’s folklife resources or about the AFA, visit alabamafolklife.org, where you can become a member, listen to the Alabama Folk podcast, watch “Folk in Five” videos and sign up for notices on upcoming events.ν