Letters tell the stories of how soldiers spent their days at the historic fort

By Emmett Burnett

Fort Morgan, the stoic garrison 20 miles from Gulf Shores, is a state historical icon. Children study the fortress of old in history class. Reenactors depict its battles. But the daily activities of the men who staffed the fort are a mystery. Take Lt. Col. Charles Stewart, for example.

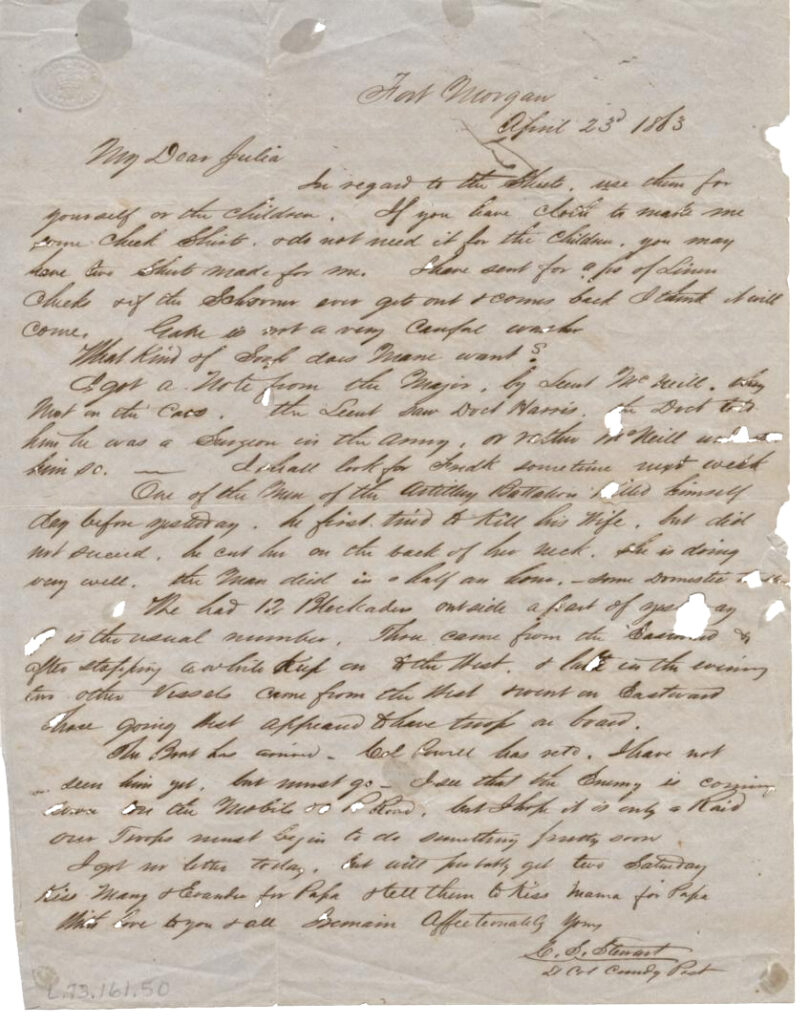

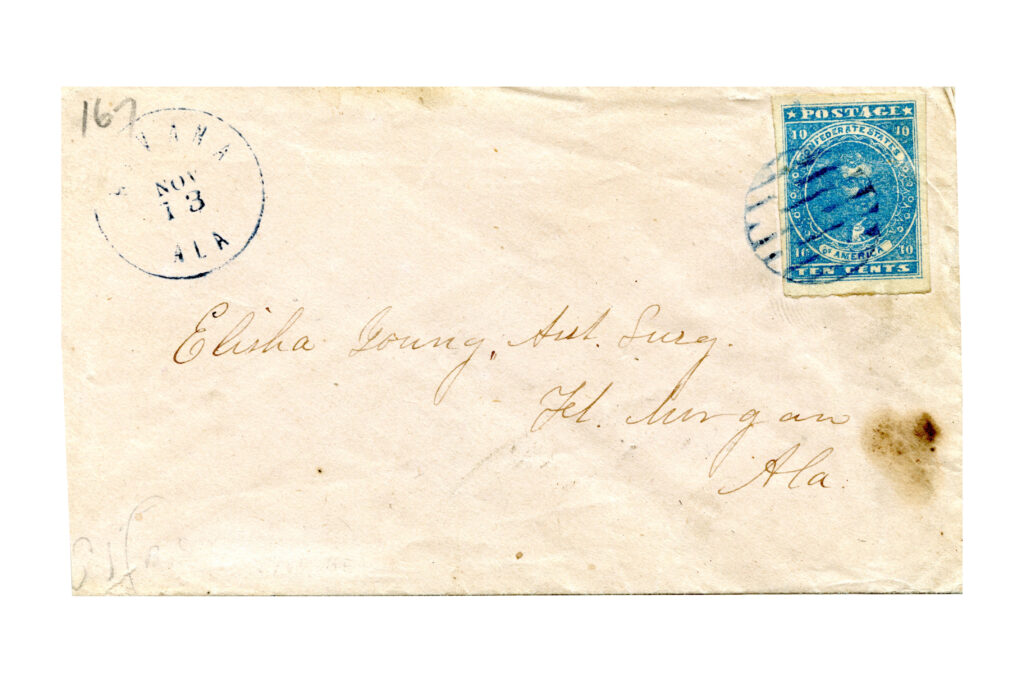

Letters from soldiers like Lt. Col. Charles Stewart’s, above, to his wife, Julia, give historians a glimpse at what life was like for the 1,000 men stationed at Fort Morgan during the Civil War. At top is an envelope sent to Elisha Young, Asst. Surgeon, and simply, Fort Morgan, Ala.

Photos provided by Fort Morgan Historic Site and the Alabama Historical Commission

Like most Confederate soldiers stationed at Fort Morgan, Stewart faithfully corresponded with family back home. On April 30, 1863, he closed a letter to his wife with, “Love to all, goodbye.” His words were prophetic.

Stewart died two hours later while test firing a faulty cannon. The weapon exploded in a rain of metal, debris, and smoke. Among the scattered remains, soldiers found Stewart’s dentures which are on display at the Fort Morgan Museum.

“Much of what we know about the men today is derived from their letters,” notes Ian McConnell, Fort Morgan’s Culture Resource Specialist, Alabama Historical Commission. “Their letters were long, eloquent, and well written. Most of the soldiers were literate and well read.”

A letter from home was a treasure, sent by boat to fort. However, timeliness was a problem. A letter to Mobile took a month to deliver. A letter from Mobile took a month to receive.

During the Civil War about 1,000-plus troops were stationed at the fort. Some were temporary, awaiting transfers. Others spent their entire career here. Few, if any, were old.

“Many were teenagers,” says McConnell, as we stroll the centuries-old fort. “These guys were in their late teens to early 20s. Officers were older, usually in their early 30s.” Stewart was 35.

“They lived in a very unique environment,” McConnell adds. The fort was as unique as the soldiers it housed.

The same year Alabama became a state, 1819, construction began on Fort Morgan. It took 15 years to build.

Bricks were hauled by oxen carts on a path that is now Alabama Highway 180.

Today the Gulf Shores to Fort Morgan trip by car takes 30 minutes. In 1819 the same trip by brick-loaded oxen cart took 10 days. There were many trips. Fort Morgan is made of 30 million bricks.

From 1819 to 1834 the fort was owned and occupied by the United States. On January 4, 1861, it was seized by the Alabama State Militia. The South took control.

From the thousands who visit Fort Morgan every year, two questions always emerge about the men who made this place happen. “They ask, ‘What did the soldiers eat and do for fun’,” notes the site’s director, Heather Tassin.

A major complaint of Fort Morgan’s troops was the food, not quality but quantity. “It was never enough,” McConnell adds. “Ration standards included pork, beef, pancakes, biscuits, and hoecakes. Much of their meals depended on the quantity of flour on hand. Flour was gold.”

He also notes, “The only way food could come in the fort was by boats from Mobile. If something cut those boats off, such as Union blockades or skirmishes in Mobile, the food was cut off, too.”

Fort Morgan’s cuisine was also supplemented with Gulf shrimp, oysters, and fish, caught by the soldiers with fishing poles and nets.

“In lean times, fish was a major addition to their diet,” McConnell adds. “Seafood saved the day.”

In addition to fishing, they had other pastimes, but no time was set aside for recreational activities. Free time was allowed only after work and drills

were done.

Physical fitness training was not necessary. The men conducted drills daily. They marched and ran everywhere, often with supplies on their backs, up and down Fort Morgan’s steep stone stairways.

One of the most coveted recreational events was the furlough, a soldier’s temporary ticket home. Furloughs were also bargaining chips. Soldiers occasionally sold their freedom tickets to other soldiers.

A week furlough could demand $50 to $80, a lot of money to supplement an enterprising enlisted man’s income. His soldier salary was $40 a week.

In-fort activities included singing. The men gathered in impromptu groups for songs. Many played musical instruments. They also enjoyed swimming in the Gulf and they also enjoyed drinking.

Whisky was part of the soldier’s rations. It served them well. “The letters home always talk about the other guy’s drinking, not the writer,” laughs McConnell. “It’s everybody but me,’ they would write.”

One man’s correspondence described with pride that his company was one of the most sober in the fort. Another wrote to his family, complaining about leadership’s “do as I say, not as I do” attitude. “They (officers) cannot in good conscience arrest common soldiers for being drunk on duty,” he scribed.

Yet Fort Morgan also had chaplains. Grace was said before every meal. Religious services were held twice on Sunday. Prayer meetings were conducted several times a week.

One religious leader set an unfortunate record. Episcopalian Chaplain Noble Leslie DeVotie fell from the fort’s Engineer’s Wharf and was washed out to sea. He was the first Alabama soldier to die in the Civil War.

Soldiers faced many hardships, including homesickness, disease and boredom.

“Just being here was a struggle,” notes Tassin. “The weather conditions, isolation, and no roads were

constant hardships.”

She adds, “What impresses me about Fort Morgan’s soldiers is their durability.”

A letter from a private noted, “Fort Morgan is a lovely place to visit but a terrible place to be a soldier.” Another letter described the military fortress: “Being at the front lines is better than being here.”

“Sickness was an issue,” adds McConnell. “The hospitals were always full.” Cholera, tuberculosis, coughs, colds, malaria, and yellow fever were common ailments.

There was also the anxiety of waiting for war. Their concerns were well founded.

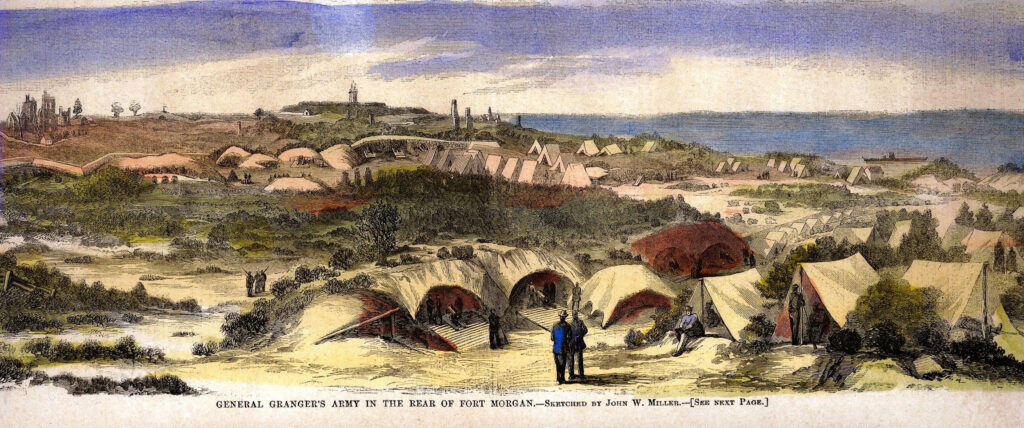

In August 1864, Union forces attacked Mobile Bay’s stronghold and its sister, Fort Gaines, in the Battle of Mobile Bay. For two weeks Fort Morgan was pummeled from attacks from land and sea.

A resulting fire raged in the fort’s interior, causing troops to dump its gunpowder in the fort’s cistern, or risk explosion. The action left the Confederate stronghold with little drinking water or ammunition. Outgunned, outnumbered and outplayed, Fort Morgan surrendered in August 1864.

The stronghold’s approximately 1,500 men were arrested and transferred to a prisoner of war facility in Elmira, NY. Others were shipped to similar facilities in New Orleans.

Years later, the fortress would be renovated and activated for military service for World War II. In 1947 the U.S. Dept. of War deeded the fort to the State of Alabama.

Today, facing Mobile Bay at the tip of the Ft. Morgan peninsula, the park and former battleground is a major state tourist destination. The fort still stands.

And in the brick and mortar halls, the memories of those who served and defended the fort still stand as well.