By Emmett Burnett

Named for a former NASA administrator, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is something to behold – but you can’t. It’s almost one million miles from earth. Though far away, the world’s most ambitious $10 billion space observatory, soon to map the deepest voids of space, has a home connection – Cullman, Alabama.

In September 2003, after head-to-head competition with Kodak (the division is now known as ITT), Cullman’s General Dynamics was chosen by NASA for JWST’s mirror project. The company would work with other space-age entities, including Ball Aerospace, Northrop Grumman, and L3Harris Technologies in making science fiction, science reality.

Thousands of scientists, engineers, and technicians from 14 countries and 29 U.S. states – and Cullman – participated in the wonders of Webb. Indeed, a wonder it is. Like the telescope, its mirrors are something to behold as well.

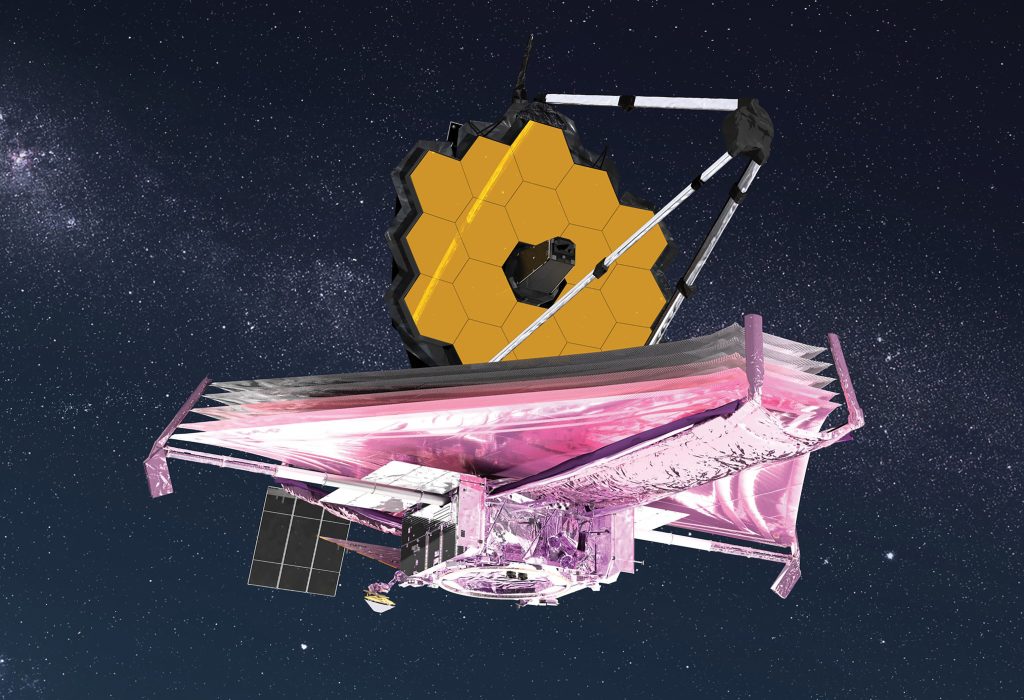

The space venture’s primary mirror, with an approximate 20 feet spread, is composed of 18 hexagon mirror segments. Each hexagon is about 4.3 feet in diameter. General Dynamics milled all 18 with three spares.

“We are proud to be part of that program,” says Jeff Calvert, General Dynamics’ Manufacturing Engineering manager. “To deliver a product the way our team did was just amazing. I cannot speak enough on how well they performed and the hours these guys spent day after day, making sure they were hitting the numbers.”

Hitting the numbers included precise milling to surgical specifications. Some sections of the hexagonal components required machine/computer measurements of what Calvert describes in layman’s terms as “the thickness of eight human hairs laid on top of each other.”

The mirrors are made of 99% pure beryllium, a steel-gray metal often found in emerald mines. As noted by Calvert, beryllium is commonly used in phones, wall plugs, computers, and electronics. Among its attractive properties, such as the ability to receive high polishing for mirror use, beryllium can withstand extreme temperatures of space, which is a good thing. The space telescope’s side facing the sun will be around 230 degrees F. The cold side will be about -370 degrees F.

Photo courtesy of NASA

“We did all the machining,” adds Calvert. “We received the hexagons weighing 475 pounds. The finished product left weighing under 46 pounds.” Team Cullman also worked on other mirrors for the telescope – secondary, steering, and support structures.

“We completed our product in a 2007 timeframe,” he says. “Other supporting structures and optics work shipped out in 2009. Once the mirrors were shipped, our contract was complete.” From Cullman, the hexagons were delivered to Ball Avionics and then to Northrop Grumman for polishing, before final delivery to NASA. General Dynamics personnel told colleagues down the line, “Take care of our parts.” Calvert smiled, “They did.”

Truly rocket science

After milling the beryllium, a thin coating of pure gold was applied to each hexagon. According to NASA, gold is very reflective, perfect for bouncing every available proton of light from distant worlds.

But as a byproduct, it is beautiful. The finished product is a glistening 21-foot diameter gold honeycomb of 18 pieces working as one. Miniature replicas in jewelry form can be purchased online.

As for explaining how the James Webb Space Telescope works, it is not rocket science – actually, yes, it is. Very much so. Do not try this at home.

“This thing had so many moving parts,” recalls Calvert, about the largest project he has been involved with during 30-plus years with General Dynamics. At 21.5 feet diameter, the primary is the largest mirror ever sent into space.

He adds, “You only have one chance to get it right. It is not serviceable. There is no coming back. It is a one-time shot.”

Like the mirrors, the observatory is also folded, encapsulated in the rocket taking it into space. Once in position, the tightly packed observatory/mirror assembly jettisons and unfolds gradually, taking weeks. When unfurled it is the approximate mass of a full size school bus.

But the other “unfolding” explained in a NASA press release is even more mind-boggling: “It (JWST) will unfold the universe, transforming how we think about the night sky and our place in the cosmos. The telescope lets us look back to see a period of cosmic history never observed. Webb can peer into the past because telescopes show us how things were – not how they are right now. It can also explore distant galaxies, farther away than any we’ve seen before.”

The light is collected in the primary lens, then bounced to the other mirrors and finally, transmitted to earth. The observatory’s telescope sees with infrared light at much greater clarity and much greater distance. According to NASA, it could discover if we are alone in the universe.

‘We have a lift off’

Fast-forward to Dec. 25, 2021. Christmas morning is breaking in Cullman, Alabama. But at General Dynamics all eyes are on events 2,000 miles away. “Lift off! We have a lift off!,” an exuberant NASA announcer proclaims at about 6:15 a.m. Cullman time. His loudspeaker words blare at the Kourou, French Guiana launch pad.

The Ariane 5 rocket ignites and flies into space, with a neatly packed payload folded like a robot from a “Transformer” movie. The James Webb Space Telescope departs earth forever.

The speaker continues, “From a tropical rain forest to the edge of time itself, James Webb begins a voyage back to the birth of the universe!” And with those words, the most expensive, most powerful, and most ambitious instrument ever made begins its stellar mission, thanks in large part to workers in Cullman.

Gazing at a starry night, General Dynamics’ program finance manager Robert Tidwell ponders the project his team put into space. “Being part of the program gives us a sense of pride for this area and to see this program come to pass,” he notes about the contributions of an Alabama-based workforce.

Calvert agrees. “I was a small part of this team,” he says, referencing General Dynamics’ Cullman group which also provides milling work for nuclear reactors, strategic missiles, satellite components and more. “But to be part of this one (JWST), the little part I had with it, is a lot of pride.”

Meanwhile back in space, on this late January morning, “the mirrors are all folded out now,” Calvert says, monitoring the observatory from Cullman. “Each of those 18 mirrors are being articulated and phased in to represent one reflective object.”

The phase in process takes a few months and then it happens: James Webb will transmit images to earth during its five- to 10-year mission.

In a few months, humankind may discover new galaxies, track unknown planets, and speculate on inhabitants of other worlds as they speculate on us.ν