Turn off the outdoor lights and step into the dark this summer and you may find yourself in an enchanted landscape where hundreds, maybe even thousands, of fireflies — and perhaps a few children carrying Mason jars — streak about in the night.

Or you may not.

Fireflies (or lightning bugs, if you prefer) are the stuff childhood memories are made of, but these bright little beetles, and possibly future memories, are also at risk.

The twinkling that attracts us to fireflies is caused by bioluminescence, a chemical reaction in their bodies that allows them to produce and emit light. Fireflies use that light to ward off predators and attract mates, the opportunity for which is but a spark in time.

The lifecycle of fireflies starts each summer when females lay eggs in or on top of the soil. The eggs hatch in about three weeks and the larvae then spend another year or two, depending on the species, maturing in the soil or in organic litter on top of the ground.

Beginning in the spring (I saw my first 2019 firefly in March) and continuing through the summer, the larvae pupate and take wing as adults on a tight schedule: They have only a short time, usually two to four weeks, to procreate before their lights go out forever.

The process is much more complicated, and fascinating, than I have space to cover in this column, but suffice it to say that among the more than 2,000 species of fireflies found throughout the world (170-plus of which are found in the United States) there is wide physical, behavioral and bioluminescent diversity — including some species that group together in synchronized light shows.

Fireflies not only delight us visually, they are also important to our ecosystems. Firefly larvae eat — and thus help control — a number of pests such as slugs, snails and worms. Adult fireflies eat very little, if at all, because they are focused on reproduction, but they help pollinate a variety of plants, may be eaten by other animals up the food chain and their bioluminescent chemicals have medical and scientific uses.

Fireflies not only delight us visually, they are also important to our ecosystems. Firefly larvae eat — and thus help control — a number of pests such as slugs, snails and worms. Adult fireflies eat very little, if at all, because they are focused on reproduction, but they help pollinate a variety of plants, may be eaten by other animals up the food chain and their bioluminescent chemicals have medical and scientific uses.

Unfortunately, fireflies are also at risk, a problem that was first detected a decade or more ago when scientists and enthusiasts began noticing a decline in firefly populations. The exact causes of this decline are still being studied, but most experts agree that habitat loss, light pollution and over-use of pesticides are the main culprits. Other human activities, changes in hydrology and — believe it or not — predation by earthworms may also contribute to the problem, as does commercial harvesting of fireflies.

Without conservation efforts, there may come a time when firefly lights go out in Alabama (and elsewhere). But luckily fireflies have advocates working to keep their lights shining, including Texas biologist Ben Pfeiffer who founded www.firefly.org, a website filled with information on fireflies and how we can help protect them.

Those of us with gardens and lawns can help the effort simply by making our landscapes firefly friendly using Pfeiffer’s simple suggestions.

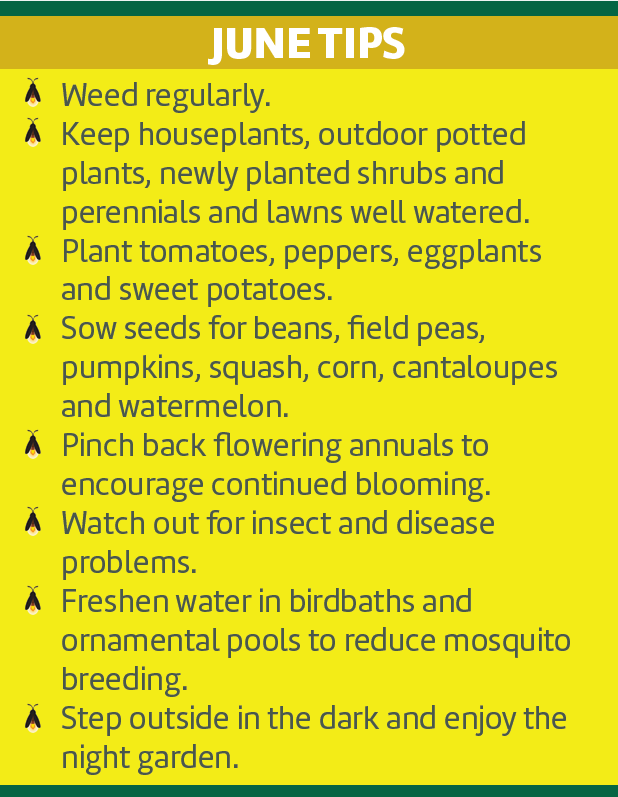

- Reduce light pollution by keeping outside lights off as much as possible and closing curtains or blinds to limit escaping interior light.

- Create firefly larvae habitat by leaving fallen logs, limbs and yard litter in place.

- Maintain or establish a water feature such as a small pond or stream or a wet or marshy area.

- Reduce, or better yet avoid, the use of pesticides, especially lawn chemicals, and limit the use of mosquito over-spraying to times when fireflies are least active.

- Leave areas of tall, uncut grass, a favorite hangout of fireflies during mating season, in parts of the yard.

- Plant native trees, shrubs and grasses.

These measures, along with many others that can be found through Pfeiffer’s website and other sources listed in the “Illuminating Information” sidebar, may help ensure that we and our children and grandchildren continue to step into enchanted summer landscapes for generations to come.

Illuminating Information

Here are some exceptional resources on fireflies and firefly protection:

- Ben Pfeiffer’s website, www.firefly.org.

- Participate in Firefly Watch at

- www.massaudubon.org/get-involved/citizen-science/firefly-watch.

- Tufts University firefly biologist Sarah Lewis’s book, Silent Sparks: The Wondrous World of Fireflies, and also her website and blog at silentsparks.com.

- Catch synchronized firefly shows each May and June at two primary sites in the Southeast, one near Elkmont, Tenn., in the Great Smoky Mountains (www.nps.gov/grsm/learn/nature/fireflies.htm) and another in South Carolina’s Congaree National Park (www.nps.gov/cong/fireflies.htm).

Conscientious Catching

Chasing and catching fireflies is an age-old joy of summer, but considering their decline, is it a good idea? Experts say it’s OK if you catch and release conscientiously.

- Use gentle collection techniques (a butterfly net is best).

- Keep fireflies no more than two days in a jar with a perforated lid.

- Add a moist paper towel or coffee filter and a slice of apple to the jar to help keep the jar’s environment firefly-friendly.

- Set fireflies free at night so they can get back to the hard work of courtship. They only have so long after all.

Firefly Talk

Though flash patterns and behaviors vary among firefly species, typically male fireflies are the ones twinkling in the air and in trees. Females hang out in tall grasses and shrubs near the ground where they can observe the selection of aerial suitors.

When a female spots an appealing fella, she usually emits a single come-hither flash inviting him in for closer inspection. At least one species of firefly, however, mimics mating flashes to lure in other firefly species for dinner — that is, to become dinner.

Watching these visual conversations can help determine which firefly species are in your area. Another great resource can be found at Science Friday radio show’s website, www.sciencefriday.com/educational-resources/talk-like-a-firefly/.

Katie Jackson is a freelance writer and editor based in Opelika, Alabama. Contact her at [email protected].