Growing up in the 1950s in South Alabama, I dreaded this time of year. The dark of winter was still upon us and spring seemed a long time coming. To make our situation all the worse, while we slogged through the cold and damp, 100 miles down the road they were celebrating.

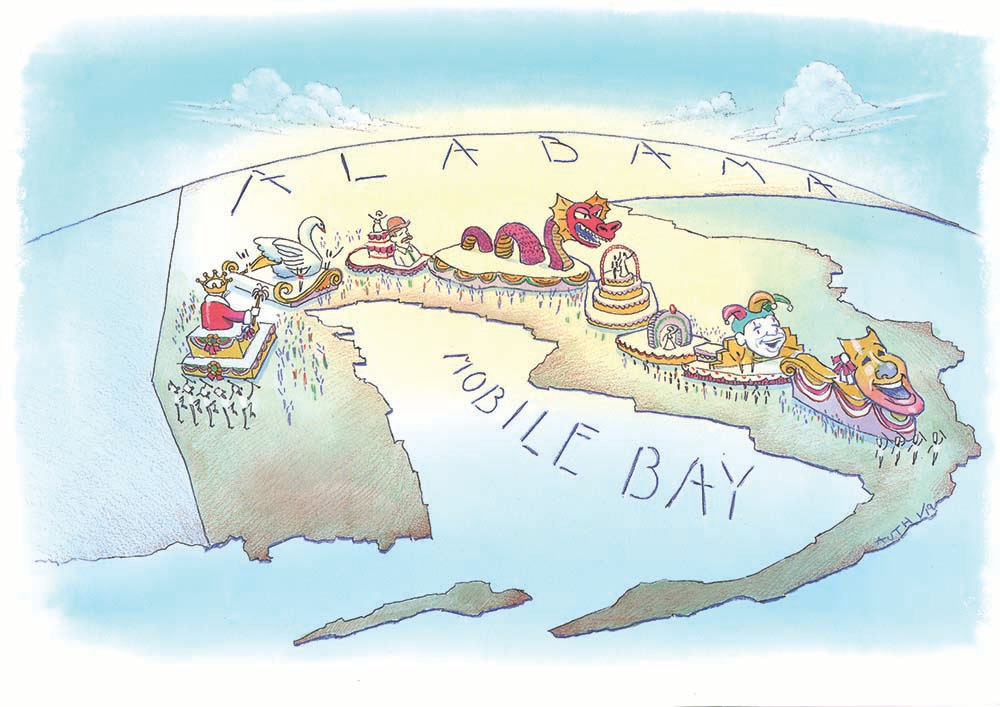

Mardi Gras in Mobile.

I naturally wanted to go, wanted to join the fun and festivities, the parades and parties and such. Unfortunately, I couldn’t.

Not just because the celebrating took place when my upcountry school was in session. I had played hooky for less attractive things.

The real reason I could not join the fun was that to really enjoy Mardi Gras you had to be on the inside, socially and economically. I wasn’t.

Mardi Gras in Mobile had always been a confirmation of class. To be in one of the Mystic Societies, ride on the floats and go to the parties, you had to have connections, status, and money.

If you didn’t, all you could do was watch the parade pass you by.

Which is what people from up my way did, if they bothered to go at all.

What I did not know at the time was that despite the best efforts of the upper classes to keep Carnival exclusive and elitist, a revolution of sorts was under way.

It started during World War II.

When America went to war, what one old Mobilian described as “the lowest type of poor whites” flocked in to work in the shipyards. Mobilians tolerated them as a wartime necessity but that was all. “I only hope,” one local wrote, that when victory is won, “we can get rid of them.”

Only they couldn’t.

Instead of leaving, many stayed to become part of the rising postwar middle class.

And there is nothing a rising middle class enjoys more than displaying the evidence of their rise.

And there was no better way for the nouveau Mobilians, the bourgeois Bubbas from the “backwoods,” to certify their arrival and assimilation than to become part of the city’s most celebrated show of status – Mardi Gras.

But they couldn’t. Most mystic societies had a waiting list loaded with the better-bred.

So, the up-and-coming created their own.

Years later a founder of one of the new associations recalled how his mystic society met in a pool hall, only charged $35 a year in dues, and “never heard of waiting lists.”

And as the barriers came down, Mardi Gras spread.

In outlying communities, folks organized their own mystic societies and let the good times roll in their own backyards.

One year the town of Chatom hosted a parade that included floats sponsored by S&S Cleaners and the Post Office. Daphne had a family-focused celebration complete with floats from Publix, the Humane Society and Chick-Fil-A (since the event wasn’t on Sunday). Prichard, Fairhope, Foley, Gulf Shores, and Orange Beach also celebrated.

Which, as far as I am concerned, is just great.

For folks looking for a break from the winter doldrums, Mardi Gras comes along at the right time.

Meanwhile, in Mobile where it all began, as the sun sets on Fat Tuesday, the Order of Myths march. And on the last float of this last parade there will be Folly chasing Death around the broken Column of Life.

A reminder that the next day is Ash Wednesday and we are mortal after all.

Harvey H. (Hardy) Jackson is Professor Emeritus of History at Jacksonville State University and a columnist for Alabama Living. He can be reached at [email protected].