Still looking for de Soto with the help of pig bones

In October of 1540, at the Indian town of Mabila, soldiers of Hernando de Soto clashed with the forces of chief Tascaluza. When the fighting was done, one Spaniard estimated that between 2,500 and 5,000 Indians lay dead. If the count is anywhere close to correct, this was the bloodiest battle fought on North American soil until Union and Confederate armies slaughtered each other at Shiloh.

Mabila was in Alabama.

We don’t know where.

Soon we might.

A few months ago, a three-university archaeological expedition set out to find where the battle was fought.

It won’t be easy.

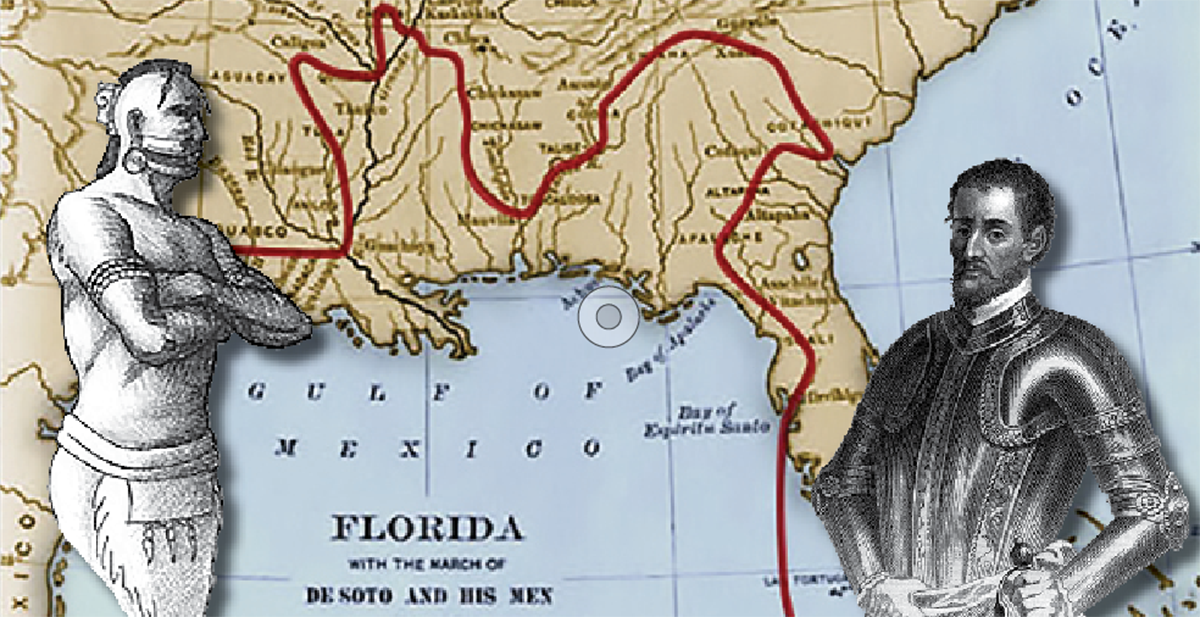

We are not even sure of the route de Soto traveled.

Back in 1939, a national commission was set up to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Spanish invasion. It identified what it felt was de Soto’s route and put Mabila down in Clarke County, where I grew up. Locals were so tickled with the honor that they named a Boy Scout Camp after the battle.

Then, years later, a cadre of anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians did another study, and concluded that Mabila was likely located farther north, where the Cahaba River empties into the Alabama, near the site of Cahawba, Alabama’s first state capital.

Couldn’t be, one critic claimed. The Spaniards wrote of meeting Indians who wore hats made from palmetto fronds and ate chestnut bread. No palmetto and chestnut at Cahawba.

Then someone produced a picture of palmetto-covered wetlands at the site and pointed to a nearby plantation called “Chestnut Hill,” which was obviously not named for the pines on the place.

The critic pouted.

Meanwhile Clarke County rejected the new findings and continued to claim Mabila as its own, an intransigence that reveals just how much it means to a community to know that history once touched it. Towns all over the state would like to attach “de Soto slept here” to their city seal.

Now if the folks leading this new expedition asked me, I’d suggest they take a look at the route-tracing scheme devised by Doug Jones of the Alabama Museum of Natural History.

You see, we have only a few sites where we know de Soto camped. At one site archeologists found pig bones.

Jones suggested that scientists extract DNA from de Soto pigs and clone modern pigs that would have the route imprinted in its genetic structure. OK, I don’t understand either, but it sounds good. Then the cloned pigs would be released and following them would confirm, once and for all, the route de Soto took.

On that route they would find Mabila.

Now the expedition may already be using this approach. If they are, I hope they do as Jones proposed and when the pigs reach their destination, throw a wing-ding barbeque.

I hope I am invited.

Harvey H. (“Hardy”) Jackson is retired professor emeritus of history at Jacksonville State University whose most recent book is The Rise and Decline of the Redneck Riviera, featured in the January 2013 Alabama Living. His work appears in the Anniston Star and Northeast Alabama Living. He can be reached at [email protected].

Harvey H. (“Hardy”) Jackson is retired professor emeritus of history at Jacksonville State University whose most recent book is The Rise and Decline of the Redneck Riviera, featured in the January 2013 Alabama Living. His work appears in the Anniston Star and Northeast Alabama Living. He can be reached at [email protected].