The other day I got a copy of John Schlimm’s new book Moonshine: A Celebration of America’s Original Rebel Spirit. Really enjoyed it.

Now let me say, up front, that to my certain knowledge I have never drunk homemade whiskey. However, I have eaten it.

I’ll get to that in a moment.

Get you a copper kettle

Get you a copper coil

Cover with new made corn mash

And nevermore you’ll toil

Albert F. Beddoe, “Copper Kettle”

That bit of verse tells you a bunch. Schlimm tells you more. He tells how hardscrabble farmers saw making and selling whiskey as a way to supplement their meager incomes, and how prohibitionists, temperance advocates, revenue agents and other busybodies tried to stop them.

Think about it from the farmers’ perspective. Most everybody grew corn, so the market was flooded. But take that corn, convert it into alcohol and you have not only reduced the bulk, making it easier to transport, you have created a commodity for which there is a ready market.

“And nevermore you’ll toil.”

The result is a story of innovation, entrepreneurship, manufacturing and distribution, a tale filled with folk heroes and daring-doings. What can be more American than that?

Closer to home, it is also an Alabama story.

I grew up in a “dry” county that was surrounded by “dry” counties. Without getting into the convoluted history of prohibition in our fair state (I’ll save that for another column) it will come as no surprise that thirsty citizens of my county turned to moonshine, which was cheaper and more readily available.

It was cheaper because it was neither taxed nor regulated by state or federal governments.

Local authorities tried to suppress it, but to little avail.

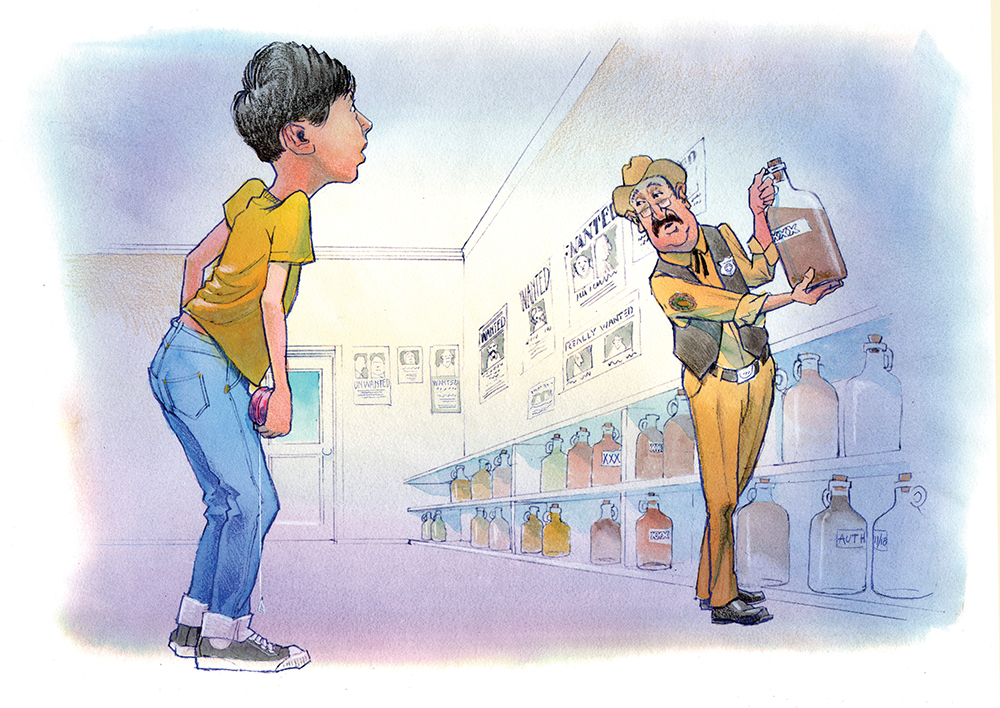

I recall as a boy walking into the sheriff’s office in our courthouse and seeing scores of gallon jugs full of a strange, brownish liquid. (My Daddy’s office was next door, which is why I was allowed in.)

A deputy, seeing me staring, picked up one of the jugs, shook it, and watched the trash in it settle to the bottom.

“Tea leaves,” he said. “Put in there to give it color so they could sell it as bourbon.”

Which gets us to yet another reason not to touch the stuff. You never know what’s in it.

Some distillers were said to put horseshoes in the mash to give it iron. Others reputedly added snakeheads to give it bite.

And there is the cat that fell into the mash and gave a name to a Monroe County community – Cat Mash.

When copper coils were not available, innovative distillers would use car radiators, the lead from which would poison the drinker.

Little wonder that at one time along rural roads in the state were billboards that read “Moonshine kills.”

But moonshine also flavors.

It flavored the fruitcake in Truman Capote’s short story “A Christmas Memory.”

And in To Kill a Mockingbird, Scout reports that “Miss Maudie baked a Lane cake so loaded with shinny it made me tight.”

Considering those literary endorsements, it is no wonder that in 2016 Alabama designated the Lane cake as the Alabama State Dessert (recipe on pp. 96-97 of Schlimm’s book).

So it was, and so it is, that moonshine has been part of our history ever since some of our sainted ancestors began running it off and selling it out. If you want to know more about it, and learn a whole bunch of ways to make it presentable to discriminating eaters and drinkers, John Schlimm’s book is a good place to start.

(MOONSHINE: A Celebration of America’s Original Rebel Spirit by John Schlimm, was published in September by Citadel Press, an imprint of Kensington Publishing.)

Harvey H. (Hardy) Jackson is Professor Emeritus of History at Jacksonville State University and a columnist for Alabama Living. He can be reached at [email protected].