made of thin galvinized tin.

By Jim Winnerman

For 20 years the 1880-era Bliss Block building and the Perry Cotton Exchange building sat vacant and deteriorating on a prime commercial corner in downtown Florence. The windows and doors were concealed by plywood and siding and much of the ornate Victorian architectural details were missing or damaged.

Still, there was something intriguing about the attached buildings that attracted the attention of local realtor and developer Jimmy Neese. When he pried back one of the panels of siding covering the street-level façade, Neese exposed the original elaborate cast iron columns. “I knew then it had potential,” he says.

Neese consulted with the late Harvey P. Jones, a prominent restoration architect in Huntsville, who recognized the historical significance of the building. “Jimmy, this was once a beautiful building and one of the most important in the community. If you restore it, you need to do it right,” Neese recalls him saying.

Three years later, and after extensive cooperation with Alabama preservationists, historians and architects, Neese had fulfilled Jones’ wish and had returned the building to its original condition in accordance with National Park Service guidelines. Missing pieces had been custom-made to match the missing ornate trim which was painted with historically accurate colors to highlight the intricate detail on the facade.

“It wasn’t a renovation project, it was a total restoration,” he says.

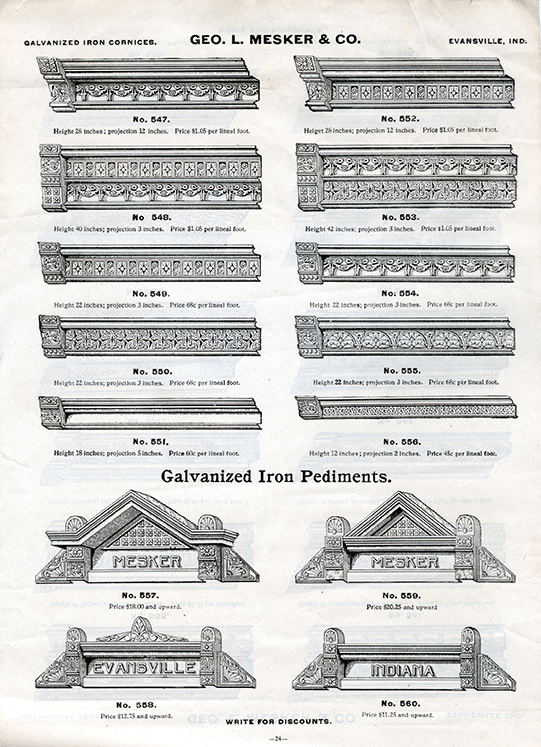

In fact Neese had rescued a superior example of what is known as a “Mesker” building. While the street-level columns and ornamentation are cast iron of the Bliss building, the window hoods and elaborate cornice with rows of medallions and draped wreaths under a pediment are very thin pressed sheet steel. On the Cotton Exchange building the stamped veneer forms a row of decorated Greek columns supporting another very imposing cornice supported by large brackets over the top of stained glass windows.

“Many people have thought the façade must be stone or wood,” Neese says.

That is exactly the perception the original owners of Mesker buildings desired. “America was still rebuilding after the Civil War, and merchants wanted their businesses to have an imposing and fashionable front to attract customers,” says Darius Bryjka, a national expert on the unique facades. “Meskers could be custom-ordered to fit any size building, and they were easily installed with local labor in just a few days.”

Only 39 Meskers are presently known to remain in Alabama. In addition to the two in Florence, they can be found in Anniston (2), Carrollton, Columbiana, Cullman (2) Demopolis, Eutaw (2), Florala, Gadsden (2), Georgiana (2), Goodwater, Greensboro (3 plus 1 demolished), Greenville (4), Hayneville, Monroeville, New Hope, Pineapple, Selma (3), Springville, Talladega, Uniontown, and Wetumpka (5).

More than 3,400 Mesker buildings in 49 states have been identified and more are reported and verified by Bryjka each month. At one time it is estimated 50,000 structures throughout the United States were once adorned with Mesker facades, but most have disappeared due to redevelopment, fire, or neglect.

The small number of remaining Meskers known to exist were all built between 1880 and 1910 and were all purchased out of a catalog, just as people at the time were shopping in the Sears and Roebuck catalog. At their height more than 500,000 Mesker catalogs were being mailed each year, but only to small town merchants.

Other firms produced pressed-metal façade storefronts, but the Mesker family was by far the largest supplier producing a wide variety of motifs on an unprecedented scale. The business origin can be traced to about 1844 when German immigrant John Bernard Mesker settled in Cincinnati and trained as a “tinner” working with tinplate.

Eventually the sons of John Mesker began their own iron works, concentrating on the production of storefronts. George continued the family business in Evansville, Ind., while Bernard and Frank Mesker opened the competing Mesker Brothers Iron Works in St. Louis.

Few Mesker buildings anywhere in the nation remain in such remarkable shape as the two Neese restored, and he has been presented with numerous state and local awards.

Billy Ray Warren, President of the Historic Preservation Inc., a community based organization in Florence, recalled recently that the corner where the Neese buildings are located had been described locally as “the most visible in the Quad Cities area. Before Jimmy got involved the buildings were an embarrassment. He brought them back to life.”

Chloe Mercer with the Alabama Historical Commission in Montgomery notes the project spurred additional façade improvements in downtown Florence and that Neese paid particular attention to maintaining the historic qualities of the two buildings, including the pressed and cast metal ornamentation on the facade and the wood and plaster finishes on the interior.”

“Every day someone comes in to tell us what beautiful buildings these are,” Neese says. “We are very conscious of their historic value and proud to have saved them for the community.”

More on Meskers

For more information on Mesker storefronts:

GotMesker.com

The Gotmesker.com website has links to a variety of Mesker resources including copies of original Mesker catalogs.

Mesker Brothers blog and facebook page

Darius Bryjka adds a new story to his Mesker Brothers blog each month. The site also adds Meskers to the national database on the stie as they are discovered.

meskerbrothers.wordpress.com/