By Emmett Burnett

A whale skull more 34 million years old found in Monroe County continues to fuel interest in paleontology and hints at the possibility of a whole new species of whale.

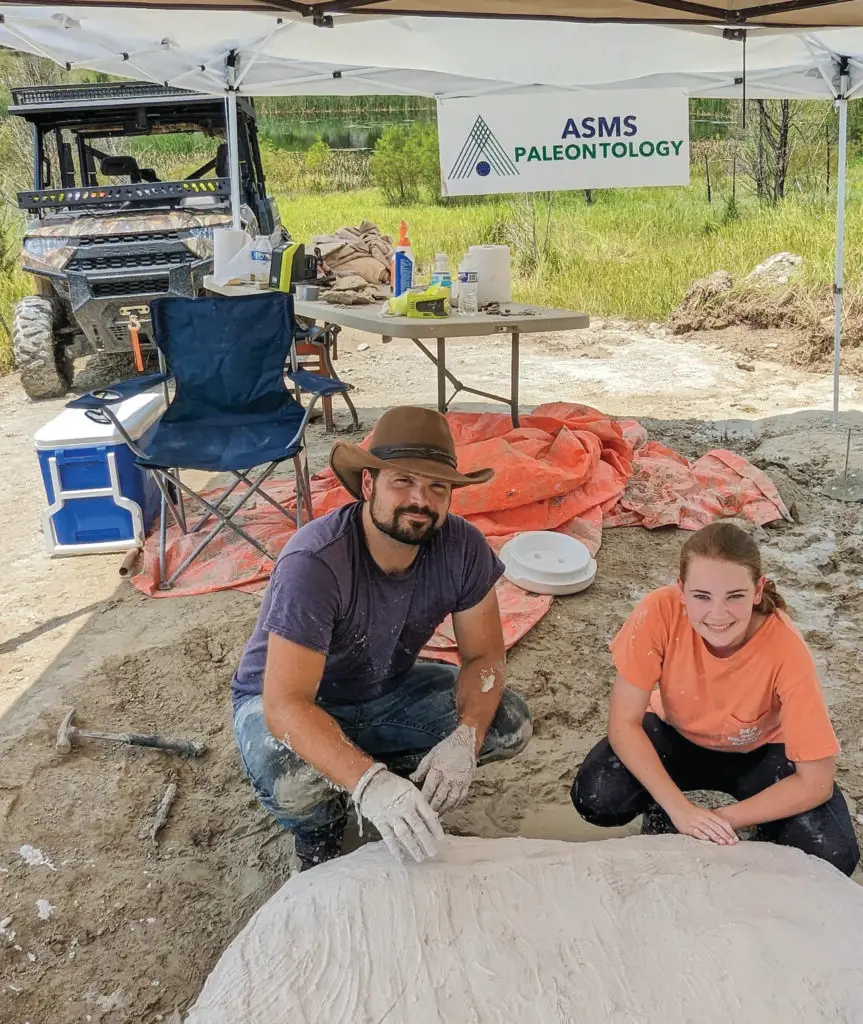

Lindsey Stallworth, a junior at the Alabama School of Mathematics and Science in Mobile, drew national attention when she and her biology and paleontology teacher Drew Gentry made an amazing discovery.

While searching for fossils on her parents’ Monroe County property in 2023, the duo unearthed the skull. USA Today, The Washington Post, Smithsonian Magazine, television, social media, and news outlets of international note chronicled Monroe County’s whale of wonder.

Today the skull resides at her school’s Paleontology Lab. Far from idle, the cranium’s story continues to evolve with research, cleaning, and preservation. How it got here is a whale of a tale that started with a bag of shark’s teeth.

In early 2023, Lindsey, then age 16, brought a bag of shells and shark teeth to school. Such artifacts are common in her Monroe County home area.

“Many families in Monroe County have properties chock full of fossils, seashells, and other bone fragments,” Lindsey says. “We are used to finding these things and often compare fossils we have obtained.”

She showed her collection to Gentry, who holds a Ph.D. in biology with expertise in paleontology. “I was particularly interested in the shark teeth she had,” Gentry recalls, from the Paleontology Lab which houses such ancient bones. “I asked Lindsey could she take me to where she found the teeth.”

In June 2023, the two visited the Stallworths’ property at Perdue Hill in Monroe County. Gentry recalls, “There were tiny pieces of bone scattered on the hillside. The pieces were getting bigger as we walked up the hill.”

And then, there it was. Shrouded in rock and earth, the whale skull protruded from the ground like the tip of an ancient iceberg. Initially, the two did not know what it was. “When seeing it, I knew this was some sort of fossilized bone but had no idea what it might be,” Gentry recalls.

Lindsey, now 17, adds about her first encounter with the head of bygone years: “I was shocked that it could actually be here. You hear about big whales and dinosaurs and all that fun stuff but never think about it being on your family’s land.”

Meticulous excavation

Many days of work ensued. Using dental picks, the two meticulously excavated the four-foot long skull from a creature that swam here when Monroe County was an ocean.

Gentry estimates the whale was about 20 feet long. It could have died a natural death or it could have been eaten with its bones spit out.

“Judging by the size of shark teeth, some four inches long, discovered in the area,” he says, “we are talking about sharks the size of a Greyhound bus. As the whale went down, other animals feasted on it too, causing bones to disperse all over the ocean floor.”

Fast forward 34 million years to now, when Perdue Hill is not 100 feet below saltwater. Days turned into weeks of digging. In addition to the whale’s skull, other bones of its anatomy were unearthed.

A tooth was discovered. “Once we found that tooth, we were able to identify that the skull belonged to a whale,” Gentry says.

The discovery was taken back to the Alabama School of Mathematics and Science’s Paleontology Lab in several trips. “The discovery was so large it was moved it in several pieces,” recalls Kelley Stallworth, Lindsey’s mom, about the skull and other bones loaded in a U-Haul trailer. “The big hole the skull left is still here on our land.”

The animal’s age was in part determined by a U.S. Geological data survey conducted previously on the area’s rock formations and land.

In addition, Jun Ebersole, director of collections at the McWane Science Center in Birmingham, estimates the whale skull to be approximately 34 million years old, based on the soil and rock the bones were embedded in. “Actually, 34 million years is a young fossil for Alabama,” Ebersole notes. “This state has fossils dating back 500 million years.”

He notes that the new discovery was from a time after dinosaurs and during the beginning of the age of mammals, including great big whales.

The creature that possessed the head of antiquity is possibly related to a whale species, Zygorhiza kochii, according to Gentry, that lived during the Oligocene epoch period.

Years of research ahead

Gentry also notes the skull could be a new species which would make the find much more significant. All agree the research and more definitive answers about the ancient animal will take months, indeed years to process.

“It’s not like what you see in ‘Jurassic Park,’” says Gentry. “Unlike the movies, ancient skeletons are rarely intact. This one is scattered all over the place.”

Meanwhile, Lindsey, the daughter of Tom and Kelley Stallworth, is a high school senior. She continues her work, devoting hours daily to cleaning and researching the prehistoric being. “It had lots of teeth,” she says with a smile, while demonstrating the tedious chore of cleaning the jaw bones and dental structures.

“I was amazed when I first saw the skull,” she notes. “Knowing something that old once lived on our property, was hard for me to process. I was amazed then and I am now.”

She, Gentry, and others continue to visit the Monroe County site, excavating and retrieving the sea creature’s bones. The process may take years to complete.

As a paleontologist, Gentry has participated in many excavations. “But I cannot think of anything that could beat this,” he says about the whale adventure. “This is right there at the top but not just from the perspective that I found something interesting. This whale has the potential to contribute great things, not just in a scientific perspective but also in a teaching perspective, getting students more engaged in paleontology.”

Lindsey is considering college and career choices including biology, marine science, or fisheries. “I love the ocean. I love the water. I want to be in it and working on it,” she says. “Fish is a great resource to feed everyone. I want a career that helps the sustainability of fish.”

In the summer of 2024, the team returned to Monroe County, digging, pulling out ribs, bits of skull, and shoulder girdles. The processing continues.

“The bone is very flaky,” Lindsey explains, “so much care and tiny tools are used to gently scrape rock from bone.”

For Lindsey Stallworth, Drew Gentry, and others involved in the task, both onsite and back in the lab, much work is ahead in a whale of a story.