Story and photos by Jonathan Shipley

There were stars on the field. There was a constellation of young men eager to play and pursue their dreams of glory. The year was 1920. The place was Birmingham, Alabama. The players were members of a newly-formed team, the Birmingham All-Stars. They were a part of the new Negro Southern League. The players, those dream chasers with balls in mitts and bats on shoulders, included men with last names like Zigler, Pickens, and Juanelo.

They played brightly, those stars on the grass. Fans from far and wide, Black and white, came to cheer them on to victory against the likes of the Montgomery Grey Sox and the Knoxville Giants; the Nashville White Sox and the Jacksonville Stars; the Atlanta Black Crackers, the New Orleans Caulfield Ads, and the Pensacola Giants.

The Birmingham All-Stars, changing their names to the Black Barons after a white Barons team was already in existence, ended the season with 43 wins and 39 losses. It wasn’t good enough for any sort of playoff run or championship, but shine they did for the city of Birmingham.

Those stars’ lights have not dimmed thanks, in part, to Dr. Layton Revel, the founder and executive director for the Center for Negro League Baseball Research and the guiding hand in the creation of Birmingham’s Negro Southern League Museum. The materials in the museum are owned by Revel. The museum is a non-profit that works in conjunction with the city of Birmingham to bring these valuable materials to the general public.

“What you see in the museum is less than 10% of the collection,” Revel says. “I do 30 to 40 hours a week researching Negro League baseball. You could say it’s a passion of mine. It’s an obsession.” For only 10% of his collection, the museum’s display cases are chock full of rare and one-of-a-kind items.

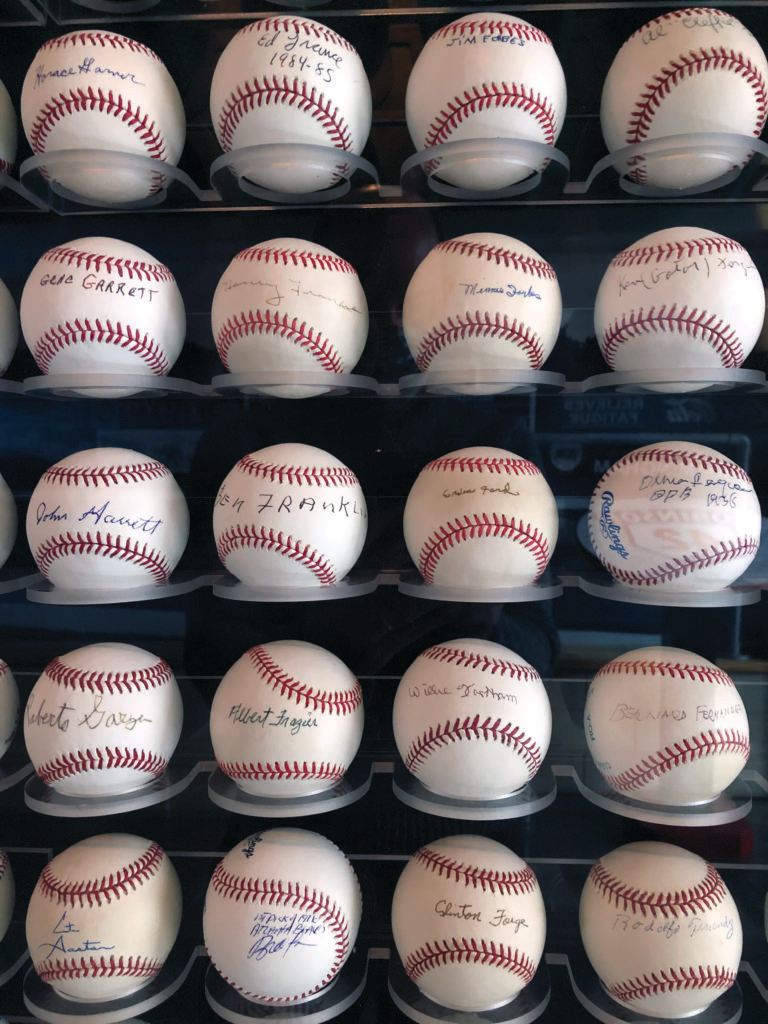

There are 1,768 signed baseballs at the start of the exhibit. Revel says, “I’ve interviewed all but six of the players who signed them.” One man who signed a ball, Otis Williams, played but one Negro League game in the 1930s before getting injured, ending his career. Another man, old and enfeebled by a stroke, was so proud to be remembered, he signed a baseball, too. With shaky hands it took him a half hour to sign a ball. Revel says, “I wouldn’t sell that ball for a million dollars.”

Also on view in the museum: Satchel Paige’s game used uniform. “I’ve sat on Satchel Paige’s porch,” Revel says. “I’ve been in Cool Papa Bell’s house. I’ve been to Bullet Rogan’s house.” Bullet Rogan’s pitching jacket is on display. Willie Wells’ game used uniform can be seen, as can the oldest known Negro League contract and the oldest Negro League trophy. There are seats in the museum from Atlanta’s old Ponce de Leon Park. Louis Santop’s bat, nicknamed “Big Bertha,” is on display. All told, it’s the largest collection of Negro League materials in the world.

Honored to be remembered

In the 1980s Revel went to a reunion of Negro League players in Kansas City, Missouri, home of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Revel met Buck O’Neill, the famed Kansas City Monarchs first baseman and manager in the Negro American League, who told him that there were, maybe, 250 Negro League players left alive and that the memorabilia (bats and balls; jerseys and cleats; posters and paraphernalia) were mostly all gone. There was not much tangible material of the Negro Leagues that remained. “I went home,” Revel says, “and thought that can’t be right.”

Through his research, which he does with like-minded individuals like assistant Cam Perron, he’s found 700-plus previously undiscovered Negro League players. He approximates that there are maybe 200 players still living today. He says, “Of everyone we’ve contacted, almost universally, they’re incredibly gracious and proud. Honored that they’re remembered for what they did and that it was important. That it is important to preserve this history and their stories.”

Birmingham’s baseball story is a rich one. It spans further back than 1920. That’s one of the reasons Revel decided to place the museum in Birmingham – the richness. Firstly, the Birmingham Black Barons had the most Negro League seasons than any other team in the nation. It operated from 1919 to 1964. Players included Hall of Famers Satchel Paige, Mule Suttles, and a young Willie Mays. Famed country singer Charley Pride played for the Black Barons.

Not only was the city home to the Black Barons, the city sent more players to the Negro Leagues than anywhere else in America. In fact, the state of Alabama sent players to the Negro Leagues more than any other. Monte Irvin (born in Haleburg), Tubby Scales (from Talladega), and a player from Mobile named Hank Aaron all played stellar ball in the Negro Leagues. “The best players came from Birmingham,” Revel says.

What’s more, the city is home to Rickwood Field, the oldest professional baseball park in the U.S. Opened in 1910, it was home for Baron and Black Baron games. It is currently the home of the Miles College baseball team.

“It’s important to know our history. To know who we are and who we can be,” Revel says. Take that man Pickens from the 1920 squad. He is still alive, at least in hearts and minds. Satchel Paige, the legend, will always be a legend. And the kids holding baseball bats by the front entrance of the museum, are wide-eyed, stars in them.

For more information on the museum, visit www.BirminghamNSLM.org