Photographer memorializes WWII veterans with images

By Lenore Vickrey

Of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II, only about 300,000 are still alive today. Jeff Rease has made it his life’s goal to memorialize as many of them as possible.

Dr. Donald E. Hayhurst

landed on Omaha Beach with a U.S. Army tank recovery unit about 10 days after the initial landing and invasion. He received five battle service stars for his participation in combat including at Normandy, the Battle of the Bulge and the Rhineland, and the French Legion of Honor for his heroic participation in the liberation of France. During his service in WWII, Hayhurst’s rank was platoon sergeant but by war’s end he’d been commissioned a 1st lieutenant. He also served in the Korean War. Hayhurst became a professor at Auburn University, helping create the Department of Political Science, and was mayor of Auburn for four years. Under his leadership, he obtained a $600,000 federal grant for urban renewal used to improve the streets of downtown Auburn. A marker for this project is at Toomer’s Corner. In November 2018, Hayhurst and a former student flew to France and toured the five landing sites for Allied forces. (Information courtesy of writer Martha Poole Simmons in the Alabama Gazette.) He now lives in Millbrook, Alabama.

They are the men and women of The Greatest Generation, the ones who as teenagers stormed the beaches at Normandy on D-Day, who fought bravely at the Battle of the Bulge, who cared for the wounded aboard Navy ships, and who lived to tell of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Since April 2019, Rease has taken photographs of 103 veterans, mostly in Alabama and a few in other states, for his online project, Portraits of Honor. Since he began, seven of those have passed away, three in the past two months.

“They all have a story,” says Rease, who works as a freelance photographer based in Birmingham. “I enjoy seeing their faces as they remember. Most remember about times back then better than the most recent days.”

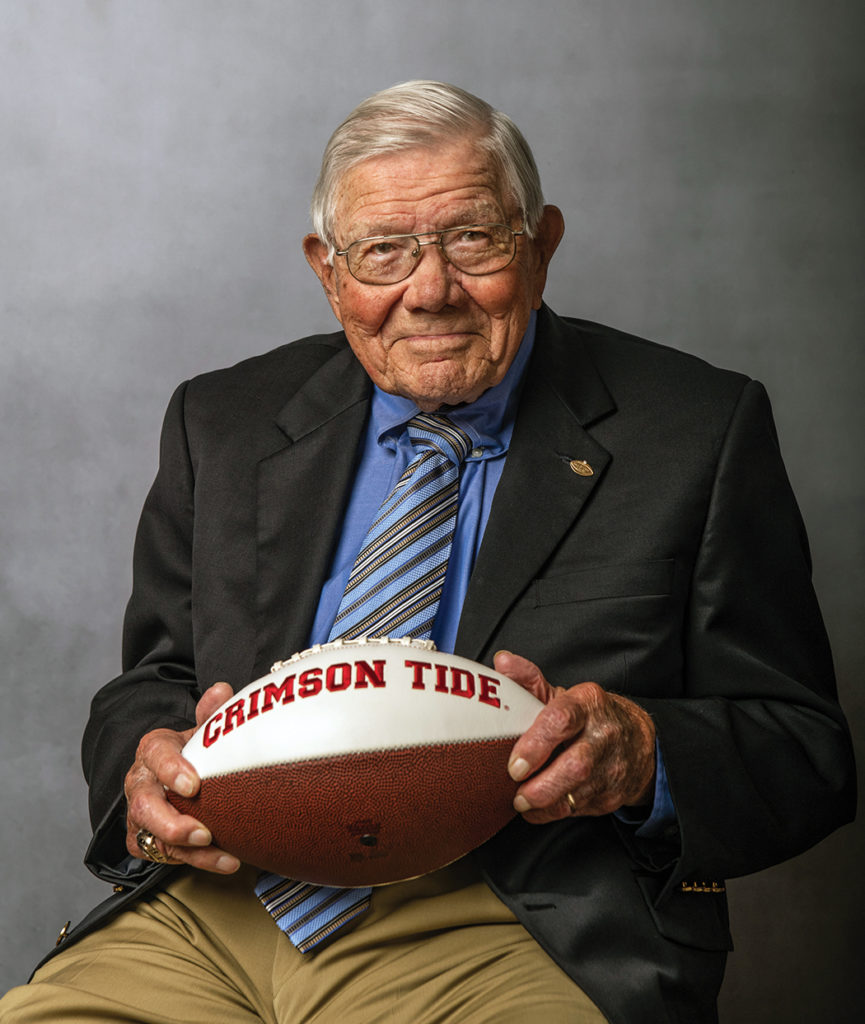

U.S. Army Lt. Don Salls,

age 101, is the oldest living University of Alabama football player, helping the Tide win the national championship in 1942 before joining the Army after graduation. Stationed in Europe for 60 days, he was shot in the hand in field combat, and after being hospitalized in England, was diagnosed with a broken back. “They said, ‘The war is over for you,’” he told Jeff Rease in a video interview. “Thank you, Lord!” Salls earned a master’s degree in physical education from Alabama, a doctorate in education from New York University, and then became head football coach at Jacksonville State University from 1946-1964, winning three bowl games and seven conference titles. In 1995 he wrote a book, How to Live and Love to be 100. He now lives at the Veterans Home in Bay Minette.

His subjects were 18 to 22 years old when they left high school or jobs in the coal mines, factories or farms and went to war. Some were even younger. They are now in their 90s and some are older than 100. One told Rease of how he joined at the age of 14, his 6-foot, 200-pound frame convincing recruiters he was older than he was. When his mother realized he was gone, she wrote a letter to the president and he was sent home from Europe. Within a few weeks, he’d joined the Navy, then the Merchant Marine, and ended up having a long military career.

Rease’s project began when he learned about a then-99-year-old veteran living close to him in the Birmingham suburbs, USMC (Ret.) Col. Carl Cooper. After Rease posted photos of Cooper on his Facebook page, wearing his Marine uniform and all his medals, a friend saw it and asked him if he could do a similar portrait of his father-in-law in Daphne. Rease was happy to do so, and one portrait led to another.

USMC (Ret.) Col. Carl Cooper

was the first veteran Jeff Rease photographed for the Portraits of Honor project. Cooper, who grew up in rural Chilton County, enlisted in 1942 and served 38 years in the USMC. Among his decorations is the Legion of Merit medal. After boot camp at Parris Island, training in North Carolina, Quantico, Virginia, and Camp Pendleton, California, he boarded a ship bound for Guadalcanal. He fought in the Battle of Okinawa, and after that, his unit moved to Guam to prepare for an invasion of Japan, until the dropping of two atomic bombs and the Japanese surrender ended the war. Col. Cooper was again called to active duty during the Korean War, serving in artillery and infantry, and during the Vietnam War, working mostly in training and recruiting in Washington, D.C. and California. He had a career later in education and coaching, and working with FEMA. He lives in suburban Birmingham where in March 2020 he celebrated his 100th birthday and was featured on local TV news programs still mowing his yard and tending his garden.

He contacted veterans homes in Alabama and the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, compiling a list of surviving veterans. “Everyone was very helpful,” he says. When he contacts the veterans, most have been eager to be part of Rease’s project. He travels to their homes, sets up a simple backdrop and lighting, chats with them and their families and puts them at ease. Some still proudly wear their uniforms and hold photos of their younger selves. Others wear suits or casual clothing. Rease puts his iPhone on a stand and records as he asks the veterans to talk about their service.

U.S. Army Nurse Beatrice Muse Price

was born in Bessemer in 1924 and grew up on a farm in Greensboro, where she learned nursing skills while caring for her father, who’d been injured in World War I. She graduated from nursing school in 1944 and became an Army nurse in 1945, three days after turning 21. While working at a hospital in Fort Devens, Massachusetts, she cared for Gen. George Patton, and later at Lockbourne Army Air Base in Columbus, Ohio, she was assigned to the Tuskegee Airmen, the first black pilots to serve in the U.S. military. After the war ended, she continued her nursing career at the VA Medical Center in Birmingham and started a health and wellness center at her church. In 2012, U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell presented Price with the Congressional Gold Medal.

Read more about her life at www.discoverstclair.com/remembering-veterans/a-life-of-firsts/

“They have some amazing stories,” he says. “Just about all are eager to talk. When some say theirs was not a glamorous role, I tell them they all contributed to winning the war.”

Some memories are more emotional than others, such as the veteran who talked about liberating a concentration camp. A B-17 pilot told of parachuting out of his plane after being shot down over France, pulling his ripcord at 3,000 feet with a jolt so strong it knocked his combat boots off, and then being rescued by farmers and being hidden from the Germans for eight weeks. Still another is one of the last surviving “Band of Brothers” and told Rease his dramatic story of parachuting into German-occupied France on D-Day, June 6, 1944, with his company, Easy Company.

Navy Electrician 1st Class Thomas Moore

will be 100 on New Year’s Eve. Originally from Moody, and then Odenville, Alabama, Moore now lives in Andalusia to be closer to one of his children. He served in the Navy and the “Secret Blue Collar War,” in which the Navy used floating dry docks to repair battle damaged ships at sea, rather than waiting for the ships to be towed to Hawaii or California for repair.

Rease has a familial connection with the military, as his father was an Army Airborne paratrooper in the Korean War, and his brother and his son both served in the Marines. A great-uncle died in WWII serving in the Coast Guard when his destroyer escort was hit by a German submarine.

“Getting to meet these veterans and talk to them, and really becoming their friends, it makes it all more real to me,” he says, “especially when you hear it directly from their mouths. I have a greater respect for the sacrifices they made.”

US Army Amphibious Forces PFC Hilman Prestridge

of Clay County was one of the first soldiers to land at Omaha Beach at Normandy on D-Day in 1944 as part of the First Infantry Division. As soon as the front landing door on the Higgins boat was dropped, heavy German machine gun fire began raking his buddies as they stepped off into the water. Many died right in front of the boat, so the rest began jumping over the sides instead. “We had these life preserver things called a Mae West around our waist,” he told Jerry C. Smith of Discover St. Clair, in 2018. “They were supposed to float up under our armpits when you filled them with air, but because we were so loaded down with so much stuff, they couldn’t do that and just hung around our waists. Lots of men died with their feet sticking out of the water because all that ammo and grenades and backpacks kept them from floating upright.” Prestridge, 19, survived and his unit stayed in France until Europe had been liberated. After the war, Prestridge came home, married, and worked at Dewberry Foundry and the Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind in Talladega. He now lives at the VA Home in Pell City.

Rease continues to travel the state and out of state to photograph veterans, working within the restrictions imposed by COVID-19. “Those who are in retirement homes I can’t go to,” he says.

He gives every veteran a large copy of his photograph and the video of his interview.

He is exploring the idea of publishing a book of the portraits, and until then, his website remains a tribute all can see at www.PortraitsofHonor.us. The site also has links to video interviews on Rease’s YouTube channel. If you know of a WWII veteran you would like Rease to photograph, you can reach him through the contact page on his website.

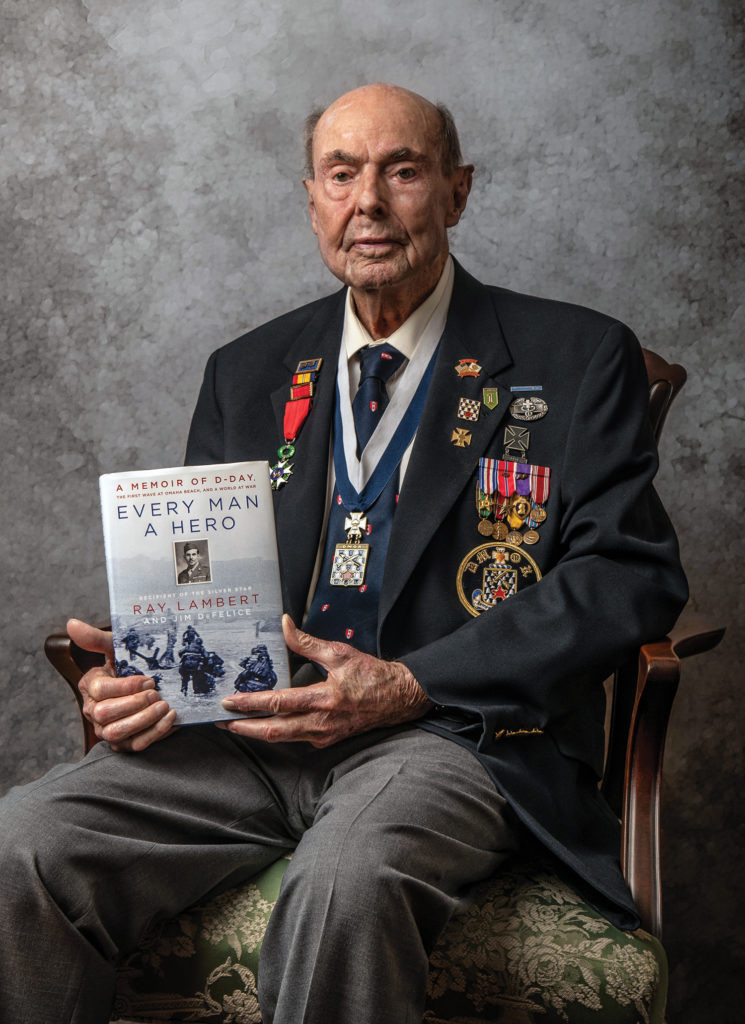

Army Medic Sgt. Ray Lambert

grew up in the Cane Creek area of rural Chilton County near Clanton. He dropped out of high school to cut timber, then joined the Army as a medic in 1940, his only medical training as an assistant to the Chilton County veterinarian. He saw action in North Africa and Sicily, winning the Silver Star for bravery. As a 24-year-old, he was sent to England to lead a team of medics, and was among the thousands who landed at Normandy on June 6, 1944. He was wounded in his arm and leg, but kept on pushing forward, helping his men, until the ramp of a Higgins boat dropped on his back, crushing his spine in two places. He recovered in a hospital in England, alongside his brother, Bill. The highly decorated veteran now lives in North Carolina and has returned to Normandy several times, most recently in 2019 at the age of 98 for the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landing. The town bolted a plaque to the concrete slab where his unit sheltered the wounded, calling it “Ray’s Rock.” Lambert tells his story in his memoir, Every Man a Hero: A Memoir of D-Day, the First Wave at Omaha Beach and a World at War, co-authored with Jim DeFelice. Watch an interview with him on YouTube.