Almost as soon as Emily Blejwas arrived here in 2004, she became enamored with the incredible diversity of Alabama’s citizens and their cultures. That interest only deepened as Blejwas (pronounced blay-voss), a native of Minnesota who now lives in Mobile with her husband and four children, discovered more of Alabama’s cultural riches while working in economic and rural development and policy roles in the state, including serving as director of former U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Regina Benjamin’s Gulf States Health Policy Center in Bayou la Batre.

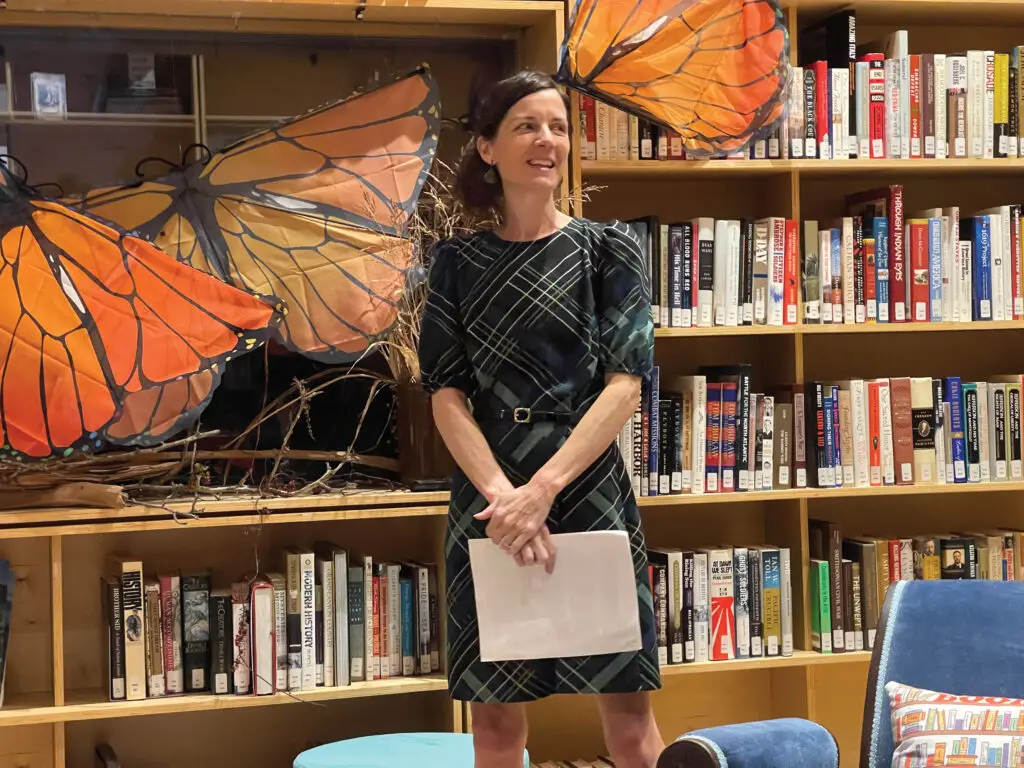

Her fascination with the state’s cultures and customs led Blejwas to volunteer with the Alabama Folklife Association, which was established in 1980 to document, preserve and promote the state’s folk traditions, old and new. She has also explored themes of community and culture as an author of three critically acclaimed books — two middle-grade novels and The Story of Alabama in Fourteen Foods, published in 2019. In 2020, Blejwas was named AFA’s executive director, a role that allows her to continue discovering, preserving and sharing Alabama’s cultural wealth through the organization’s research, education and fellowship programs and its Alabama Folk podcast. In her quest to find, protect and elevate the state’s cultural riches, Blejwas has also become one of its treasures.

– Katie Jackson

As a transplant to Alabama, was the state’s culture and cultural diversity different from your expectations or your experiences in other places you’ve lived and worked?

One hundred percent. I knew very little about Alabama when I arrived and didn’t anticipate the stunning diversity within its borders, including racial, cultural, geographic, religious, even biodiversity. I didn’t know we had four Southeast Asian communities in the bayou or barbecue sauces based in tiny hamlets or cultural traditions ranging from clogging and chicken stew in north Alabama to red snapper and Mardi Gras on the Gulf Coast. It still astonishes me, and it still frustrates me that Alabama gets painted in such broad strokes. None of us is one thing, Alabama included.

Was there an event, tradition or moment that led you to embrace Alabama so fully?

It was a pretty immediate transformation. In my first summer I met Joe Minter (an Alabama sculptor) and toured his art grounds in Birmingham, listened to (Alabama author) Kathryn Tucker Windham tell stories at the Okra Festival in Burkville and rolled through Hurricane Ivan. I started a master’s program at Auburn a few months later, which allowed me to dig even deeper into Alabama history and culture. And the more I learned and experienced, the more there was to learn and experience, like walking toward a mountain that keeps moving further away, but in a spectacular way.

Why do culture and the concept of “community” matter to us all? And to you personally?

I think it’s a matter of identity and a way of making sense of the world. Most of us, at some point, ask the big questions. What are we doing here? What is this all about? What matters? And I think both culture and community give us a sense of place and belonging and purpose. Plus, we’re all part of multiple communities that define us in different ways. They help us know who we are and to navigate the future, but also to connect back to the past.

Have you and your family discovered any folkways that you now incorporate in your own lives?

My husband’s family is Polish, so we keep many Polish traditions — chalking the lintel and hiding the coin on Three Kings Day, baking a lamb cake at Easter, sharing opłatek on Christmas Eve. In Alabama, we go to as many festivals and cultural events as we can, so we’re constantly engaged and surprised. I particularly love seeing the widows at the cemetery on (Mobile’s) Joe Cain Day. We also love hiking in North Alabama. It’s so different than Mobile, we feel like we’ve traveled far from home. I call it crossing the Sun Drop line — when you start to see Sun Drop soda in the gas stations — that’s when you’ve made it.

What are your hopes and dreams for the AFA and the state’s folkways?

I hope our work will motivate Alabamians to document and share their own traditions. The incredible thing about folklife is that we all have it. And we also have the capability to document and share it. It can be as simple as interviewing your grandfather at a family gathering or calling your aunt for that recipe (though she probably didn’t write it down) or photographing a community tradition or digging into archives to tell a local story. I’m also deeply inspired by emerging work that uses arts and culture to tell historic truths and work toward reconciliation. It’s such powerful and transformative and necessary work.