Negro Southern League Museum will honor baseball’s past

By Ryan Whirty

It’s been a long, long wait, but on July 4 — the most American of holidays — Birmingham resident and former Negro Leaguer Ernest Fann will finally get to see the story of segregation-era, African-American baseball come to life.

That’s when the state-of-the-art, interactive, multimillion-dollar Negro Southern League Museum that’s been in the works for five years will, at long last, hold its grand opening. After years of budget delays and controversy surrounding its possible competition with the long-established Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, the project sponsored by Birmingham Mayor William Bell will come to fruition.

“I’m very excited,” says Fann, a native of Macon, Ga., who settled in Birmingham after his playing career. “It took so long. There’s no museum that can tell the story of black baseball like it really was than this place. It’s going to be amazing. People will get to see the long history of the Negro Leagues, and I’m very glad to be a part of it.”

Home-grown talent

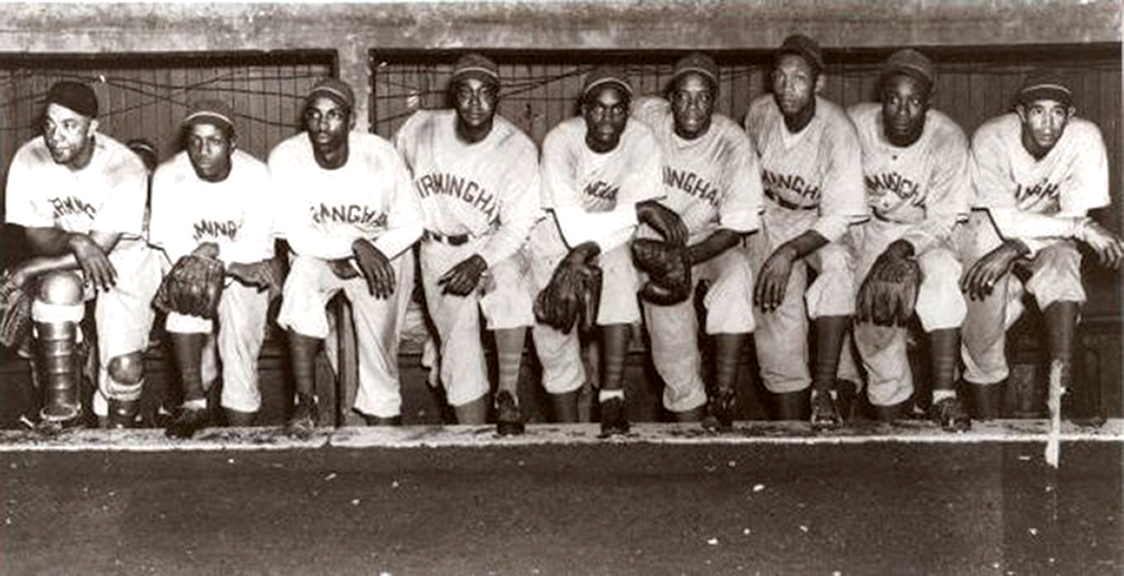

Alabama has actually played a major role in the history of African-American baseball. The state’s largest city was home to one of the Negro Leagues’ oldest, most storied franchises, the Birmingham Black Barons, which for decades was the deep South’s black baseball jewel. The Black Barons won multiple Negro American League pennants with rosters that featured dozens of African-American hardball stars, including, in the late 1940s, a young prospect named Willie Mays.

The area was also the home of arguably the country’s best, most talent-laden and vigorously competitive urban industrial leagues, which launched the professional baseball careers of dozens of African-American players.

“There’s more to the history of black baseball than just the Negro Leagues,” says Dr. Layton Revel of the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, who personally donated tens of thousands of artifacts and pieces of memorabilia to the new museum.

“A lot of the industrial teams were proving grounds for players. What we’re saying is that it’s an important part of the history. You can’t forget the grass roots, where these guys started.”

But it wasn’t just the Magic City that featured prime black baseball in the decades before Jackie Robinson broke the Major League color barrier. There were also squads like the Montgomery Grey Sox and the Mobile Black Shippers and Black Bears.

In fact, Mobile turned out to be a key locus of African-American hardball activity, not only by hosting such quality semipro teams like the Bears and the Shippers, but also serving as the hometown of the one and only Leroy “Satchel” Paige. Paige was the first Negro Leaguer inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, who many baseball historians consider the greatest pitcher in the sport’s history, black or white, regardless of time period.

Paige grew up and earned his spikes in Mobile with another Negro League legend from the city, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, one of black baseball’s most colorful, versatile, active and longest-living personalities.

Radcliffe, who died in 2005 at the age of 103, earned his nickname by catching one end of a doubleheader, then pitching the second game on the same day. When asked by author Brent Kelley in 2000 whether he considered himself a pitcher or a catcher, Radcliffe’s answer probably echoed the feelings of countless Negro Leaguers. “It didn’t make no difference,” he said, “just so we won.”

Alabama also gave birth to several other Negro League greats and Baseball Hall of Famers, like hulking power hitter George “Mule” Suttles. Then, of course, there were the two ’Bama natives and home run kings who began their careers in the Negro Leagues before moving on to greatness in the Majors — Mays and Henry Aaron.

But a slew of other, less-heralded Negro League legends came from the state, from both major cities and tiny towns scattered across the landscape.

One was Birmingham native William “Dizzy” Dismukes, who enjoyed a lengthy, storied pitching career that began in 1910 and extended into the 1940s. Later in his baseball life, Dismukes became a wily, successful manager, a prominent sportswriter in the African-American press and a scout for the New York Yankees.

Just a few years before Dismukes got his start in the top levels of the game, C.I. Taylor founded one of Birmingham’s first professional blackball teams, the Giants, who featured the playing services of C.I.’s three equally talented brothers — “Steel Arm” Johnny, “Candy” Jim and Ben. The quartet of siblings would move on from Birmingham to become the Negro Leagues’ “first family” for 20 years.

Other talented Negro Leaguers from Alabama included first baseman Lyman Bostock Sr. of Birmingham; catcher Otha Bailey Sr., from Huntsville, one of the best defensive backstops in the game in the 1950s; utility player and manager Tommy Sampson of Calhoun; pitcher Eugene Scruggs from Meridianville; Birmingham infielder Henry Elmore; outfielder and Fairfield native Jake Sanders; and the sterling infielder Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, whose famed nickname came from his hometown of Piper and who became the first African-American signed by the Boston Red Sox organization.

There was Montevallo native Clifford DuBose, a third baseman and outfielder who competed for the Black Barons and Memphis Red Sox and whose attitude toward the game symbolized the feelings of the thousands of African Americans who suited up in the Negro Leagues.

“That was such a big thing going for him,” said his brother, Glover DuBose, of Clifford’s time in the Negro bigs and beyond. “He was always a baseball man. That was his passion, baseball.”

For all of these teams and players — those famous or forgotten, honored or unsung, big-city boys and small-town kids — Revel said it’s only natural that the city of Birmingham and the state of Alabama play host to a brand-new black baseball museum.

Making a dream a reality

Making a dream a reality

The fact that the project has survived several funding hiccups points to the determination of those involved, including the dozens of players who gather in Birmingham each spring for an annual Negro Leagues reunion and who, like Fann, have eagerly and patiently awaited the realization of the facility.

But financial difficulties weren’t the only problematic facets of the project. When Revel and city officials first announced the creation of the effort, representatives from the existing Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City expressed concern that the Alabama institution would constitute a rival that could possibly draw attention, visitors and business away from the NLBM.

But since then, any conflicts between the two facilities appear to have been smoothed over, thanks to assurances from Bell, Revel and others that the new Birmingham museum would serve a totally different purpose than the NLBM, which is much more national in scope than the Alabama-based facility.

The new museum has been funded by a mix of charitable fundraising, private donations and public funding — the Birmingham City Council, for example, approved a $2.8 million appropriation to the effort last year.

Through it all, everyone involved in the museum and the annual reunion has said the facility and festivities come down to one thing — celebrating the courage, passion and playing abilities of the men (and occasionally women) in Alabama who populated all levels of African-American baseball for over a century.

“You set a standard that sent other players on to the Major League,” Bell said at a news conference last year while surrounded by former Negro Leaguers. “This is a great day, just the beginning.”

Bell made those comments as the fifth annual Negro Leagues reunion was getting underway last year. This year’s event was held May 25-27, and like clockwork, Ernest Fann was in attendance, even volunteering to chauffeur some of his colleagues around the city.

Fann said he’s encouraged by all the youngsters who attend the reunions and get a chance to talk with former Negro Leaguers about the players’ experiences on and off the diamond.

“It’s good for them to know who we are and what we did,” he said. “It’s a good chance to educate the kids.”

Meanwhile, Revel said undertaking the museum project, as well as holding the yearly reunions, is important to do now because, as the former players get on in years and pass away, memories of and connections to the Negro Leagues dwindle and fade.

“Every year we’re just trying to do more as [the players] age, and we have lots of players from Birmingham,” he said. “That’s why it’s so important to do this while they’re still alive, so we can interview them and talk to them. And they’re not just passing away, but for many of them their health is such that they can’t [relate their stories]. If we’re interested in Negro League baseball, now is the time to do it.”

New book looks back at Negro Southern League

New book looks back at Negro Southern League

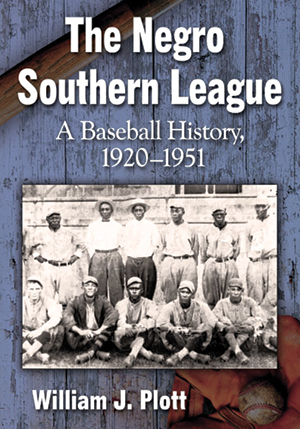

The Negro Southern League became a valuable feeder of young players to the Negro National League and Negro American League, giving starts to future baseball legends Leroy “Satchel” Paige and Willie Mays.

Now, The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951, (McFarland and Co., 276 pages, $39.95) by retired journalist and freelance writer William Plott of Montevallo, tells the story of this minor league, which sent a number of players – some found in cotton fields, some in steel mills — on to the higher level of pro baseball.

The league gave a home to professional baseball in cities that couldn’t support teams at the Negro National League level, with teams in New Orleans, Montgomery, Nashville, Pensacola, Knoxville, Jacksonville, Birmingham and Atlanta. During its history, more than 80 teams were members of the league, representing 40 cities in a dozen states. In the end, only four teams remained, operating more as semipro than professional teams.