Co-ops pulled together to recover from April 2011 tornadoes

By Allison Griffin

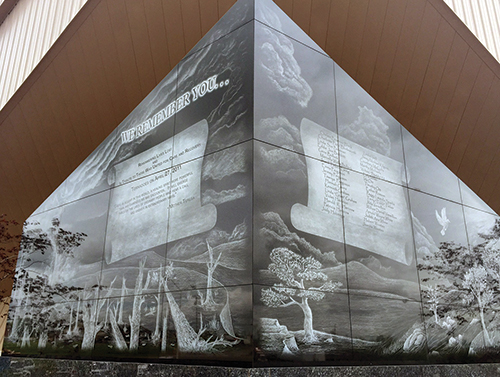

The tornado outbreak of April 27, 2011 was unlike any in Alabama’s history.

The statistics are jarring: 351 tornadoes swept through the Southeastern U.S. in just three days. The deadliest day was April 27, when a record 62 tornadoes, including eight EF-4 and three EF-5 tornadoes, struck Alabama. There were a total of 247 fatalities, more than 2,000 injuries and $4.2 billion in property damage. The storms affected 35 counties, and caused deaths in 19 of those counties. It was the third deadliest event in recent U.S. history.

The destruction was immediate and devastating. Landmarks, churches, businesses, farms and family homes were damaged or obliterated. First responders and emergency personnel found roads, and in some cases entire areas, impassable. Communities struggled to cope with the damage to infrastructure. Survivors sifted through the rubble of their possessions and their lives.

For employees of rural electric cooperatives, there was little time to grieve. Residents in north and central Alabama were only just beginning to comprehend the breadth of the destruction when their co-ops were already mobilizing crews to rebuild power lines.

The task was formidable. The TVA transmission system, which supplies power to the north Alabama distribution cooperatives, had suffered the worst damage in its history. Three hundred and fifty-three TVA transmission stations were damaged, and 108 transmission lines were out of service. More than 850,000 customers throughout the TVA service area were without power, including 450,000 customers in north Alabama.

Electric co-op crews across north Alabama started working on restoration as early as mid-morning, after the first wave of tornadoes. Most also called for help from the Alabama Rural Electric Association (AREA), which coordinates line crews to help in the aftermath of storms.

Seven tornadoes touched down in the Sand Mountain EC service area in northeast Alabama. As more storms formed, General Manager Mike Simpson and his employees felt they were continually losing ground. There was massive damage to one of their substations, but the crews couldn’t start making repairs because they were helping clear roads.

‘The worst storm I’ve ever had to deal with’

“That was without a doubt the most helpless feeling in my 35-plus years of being in the power business, and my 20 years as a manager,” Simpson says. “That’s the worst storm I’ve ever had to deal with.”

Black Warrior EMC in west Alabama was still reeling from an April 15 tornado that had affected Choctaw County at the far southern end of its system. Then, two weeks later, the tornadoes cut a swath through the area near Greensboro, in the northern part of its system. More than half its customers were without power.

Because Black Warrior’s territory is very rural, there wasn’t the concentration of damage that the cities of Tuscaloosa and Birmingham suffered. Black Warrior Operations Superintendent Robbie Rose, who was a lineman in 2011, went with crews to Tuscaloosa a few days later.

“It was devastating. Houses everywhere. Concrete power poles lying across the road. It was just total devastation. It’s hard to get ready for something like that,” he says.

The folks at Cullman EC watched from the co-op as an EF-4 tornado passed through the city of Cullman. Jason Saunders, who at the time worked on the AREA safety staff, was at the Cullman co-op that day, and on April 28 traveled through the Coosa Valley EC and Cherokee EC areas, which also suffered damage and deaths. He finally made it to Sand Mountain EC to offer help there.

“Little did I know that this event was not about just rebuilding cooperative lines,” Saunders says. “This was about rebuilding communities. As I peered out across the parking lot, the county EMA had set up a makeshift morgue sitting literally outside the fence of the cooperative.”

Co-op employees across the northern part of the state were either directly or indirectly affected; some lost homes, friends and family, Saunders says. But they told stories of what they did to help without hesitation, all while continuing to rebuild their system.

Perhaps the takeaway is the sense of community that enabled neighbors to work through their grief and to help one another. Every co-op has stories about co-ops from Alabama and neighboring states that sent line crews to set poles and hang wire and right-of-way crews to clear debris and cut trees. Countless office staff answered calls and arranged for meals, and warehouse employees helped with constant delivery of new materials and supplies.

And there are the restaurants, businesses and churches that stepped in to feed all these working folks and to help with housing.

Such outpourings of help, even in the worst of circumstances, are at the core of the cooperative spirit.

“Sometimes,” Saunders says, “It is when we are at our weakest point that we find our strength in God, friends, and our extended cooperative families.”