By Emmett Burnett

In the fall, a presidential politician prepared for meeting constituents to gain their support. Sound familiar? It’s not.

This visit occurred in October 1905 when a state-of-the art locomotive pulled out of Washington D.C. On board was the President of the United States, Alabama-bound.

Theodore Roosevelt was a man on a mission.

He wanted support for building the Panama Canal, post-war reconciliation between former Confederates and Federals, and navigation through thorny issues about African-American participation in Republican politics.

America’s 26th President visited Mobile, Montgomery, Birmingham, and Tuskegee. It would not be easy. In the presidential election, Alabamians voted against Roosevelt by 75 percent.

With apprehension, the train chugged south.

“This kind of train tour was long established,” Dr. Martin T. Olliff, professor of history and director of the Wiregrass Archives at Troy University’s Dothan Campus, recalls. “The train tour was nothing new. What was new is that Roosevelt was the first sitting president to visit Alabama. That was a very big deal.”

Indeed it was.

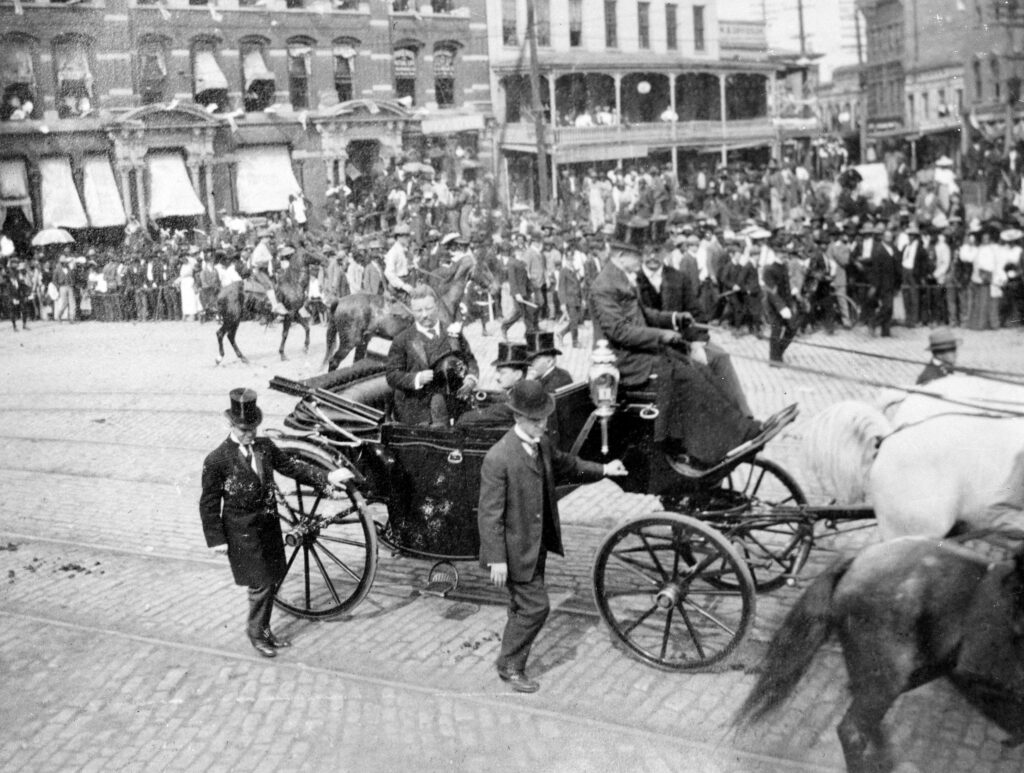

Roosevelt reached Mobile on Oct. 23, 1905. To coin a cliché, “the crowd went wild.”

The Mobile Register described the setting vividly: “For at no time in this city has there been such a demonstration as greeted Mr. Roosevelt, during the two hours he spent here. Every man, woman, and child who could walk, lined the sidewalks along the parade route or assembled in Bienville Square to await the president’s coming.”

As the train entered the city limits the press noted, “every whistle from every dockside ship, factories, schools, and churches sounded whistles and rang bells.”

During his visit, an estimated 600 school children sang “My Country ‘Tis of Thee,” “O Columbia” and other patriotic songs. Visibly moved, the President turned to Mobile Mayor Patrick Lyons and said, “What a great night.”

Bienville Square’s crowd size was estimated at 35,000. By perspective, in 1905, Mobile was a city of 40,000, meaning almost the entire population was in the park. Even more lined Roosevelt’s parade route.

During the procession’s drive on Government Street, the president tipped his hat to the Admiral Raphael Semmes Statue. The crowd roared louder.

“Roosevelt constantly noted Civil War veterans in his audiences,” adds Dr. Olliff. “Bowing to the statue was part of his reconciliation efforts between the Union and Confederates.”

The president entered Bienville Square with thunderous ovations. “It felt like the earth trembled,” one scribe penned.

Addressing a crowd that covered almost every square inch of downtown Mobile, Roosevelt said, “I cannot sufficiently express my appreciation of the magnificent greeting that you have given me today.”

Building support for the Panama Canal

He then made his pitch, saying, “In speaking before the citizens of this great seaport of the gulf, I naturally wish to say a word about the Panama Canal. Now, I hold that as a matter of public policy, whatever helps a part of our country helps the whole, and I did my best to bring about the construction of that canal in the interest of all our people, but if there was any one section to be most benefited by it, it was the section that includes the gulf states.”

Dr. Olliff notes, “U.S. House Sen. John Tyler Morgan of Alabama was a powerful force in those days. For years, Morgan’s passion was building a Nicaraguan Canal, which he felt would be of greater benefit to Alabama, especially Mobile’s seaport.”

But when Panama dropped the canal project’s price from $109 million to $40 million, Roosevelt jumped on it.

Morgan was furious and so was Alabama. T.R. was here to make amends.

In addition to the proposed Panama Canal, reporters noted another marvel: incandescent lightbulbs in Bienville Square, new technology in 1905.

Leaving Mobile, the president’s train pulled into Tuskegee and the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute – literally. It clickety-clacked straight onto the school’s private railroad tracks.

Today that would be like Air Force One landing at your dorm.

Waiting to greet the president was the school’s principal, Booker T. Washington. The two men boarded a horse-drawn carriage, built by Tuskegee students, for a school tour.

“Mr. Washington, I was prepared to see what would impress me and please me,” Roosevelt said, opening his speech. “But I had no idea that I would be so deeply impressed, so deeply pleased as I have been. I did not realize the extent of your work. I did not realize how much you were doing.”

Back to Montgomery, the President addressed thousands from the State Capitol. He made an appeal to a crowd still raw from America’s Civil War which had ended 40 years earlier.

“If you only think of it, the essential point in our lives is the likenesses in our lives, not the dissimilarities,” the president noted. “Some people lead their lives in positions of more prominence than others, but if they are decent people, if they are good people, they show just the same kind of quality, just the same kind of virtue in one place as the other.”

He continued, “The good citizen, the man who has done good to his country, is the man who, whether he is a very wealthy man or whether he has but a day’s bread by that day’s toil, whether he is an officer or private in the ranks of life, has done his duty as the Lord gives him light to see. His duty is the position he occupies.”

From Montgomery, Roosevelt’s futuristic words warned about foreign trade. “Our influence in the Orient must be kept at such a pitch as will insure our being able to guarantee fair treatment to our merchants and manufacturers in the markets of China.”

The next stop was the Birmingham State Fairgrounds. Upon arrival at the fairgrounds and surrounding areas, a conservative estimate of 100,000 people waited.

During Birmingham’s parade which included bands, the military, and Roosevelt, the president noticed a woman riding horseback parallel to his carriage. He reached for Miss Sammie Harris’ hand. Referencing the parade crowd, he told her, “I would run over a man any time to shake hands with a lady.”

Greeting fairground masses, Roosevelt explained, “I have been profoundly moved by the way in which, at every place we stopped, I have been greeted by the veterans of the Civil War. And here in Birmingham not only by the veterans who wore the gray, but also by those who wore the blue.

“And, oh, my fellow countrymen, think what good fortune is ours, that we are the heritors of the one great war in history which, now that the bitterness has died away, has left the memory of men in the Confederate uniform and of men in the Union uniform as a common heritage of glory to our entire people.”

After the speech, Roosevelt boarded an electric street car for a brief tour of the fairgrounds.

From Birmingham, his train left Alabama, eventually returning to the nation’s capital.

What a difference 119 years make. In 1905 horses were a viable mode of transportation. News photography was in its infancy. Radio was a rumor.

Until his visit, most Alabamians had never heard Roosevelt’s voice and knew little of what he looked like, beyond artists’ sketches.

That changed in October 1905, when a New Yorker, elected president, came to Alabama. Roosevelt’s dream of building the Panama Canal came true.ν

Note: The story of Roosevelt’s visit to Alabama is based in part on the Mobile Register’s October 1905 newspaper accounts. The president’s speech excerpts are from The American Presidency Project.