Come on “oldsters,” dust off your memories and work with me now.

Remember how important May Day used to be?

That was when elementary schools around the state used to put on “May Day Programs.”

As the weather warmed, and the sap started rising, those programs gave teachers a way to control and contain all that pre-teen energy.

Recess only stirred up the juices that bubbled beneath the surface.

Back in un-air conditioned classrooms, students sweated and sweltered, dozed and drooped. Energy collected within them, looking for a way to get out.

Teachers dreaded this time of year, for student minds were on everything but their studies.

But what could teachers do?

Then someone, some hero, pointed out that right slap dab in the middle of this mess was MAY DAY.

Yessir!

It was the day that, historically, working folks around the world celebrated the liberation from winter’s grip and the arrival of spring.

So why not celebrate in South Alabama?

Now admittedly, in Grove Hill, by the first of May, spring had already sprung. Buds had budded, kudzu was crawling, fields were plowed, and some early crops were in the ground, waiting for the warm.

No matter.

When April showers kept children indoors, teachers brought out the bright paper, colorful crayons, dangerous scissors, and other instruments they hoped would keep us quiet until the rains passed and they could send us to the playground.

We, the children, reasoned that our liberation would come on May 1.

Though few of us knew at the time, this belief was part of a long and respected tradition. In agricultural societies, the First of May was a pause before planting.

It was a signal date, telling one and all, that “lo the winter is past.” (Song of Solomon 2:11-12)

Which, in elementary schools across the Deep South, meant only one thing.

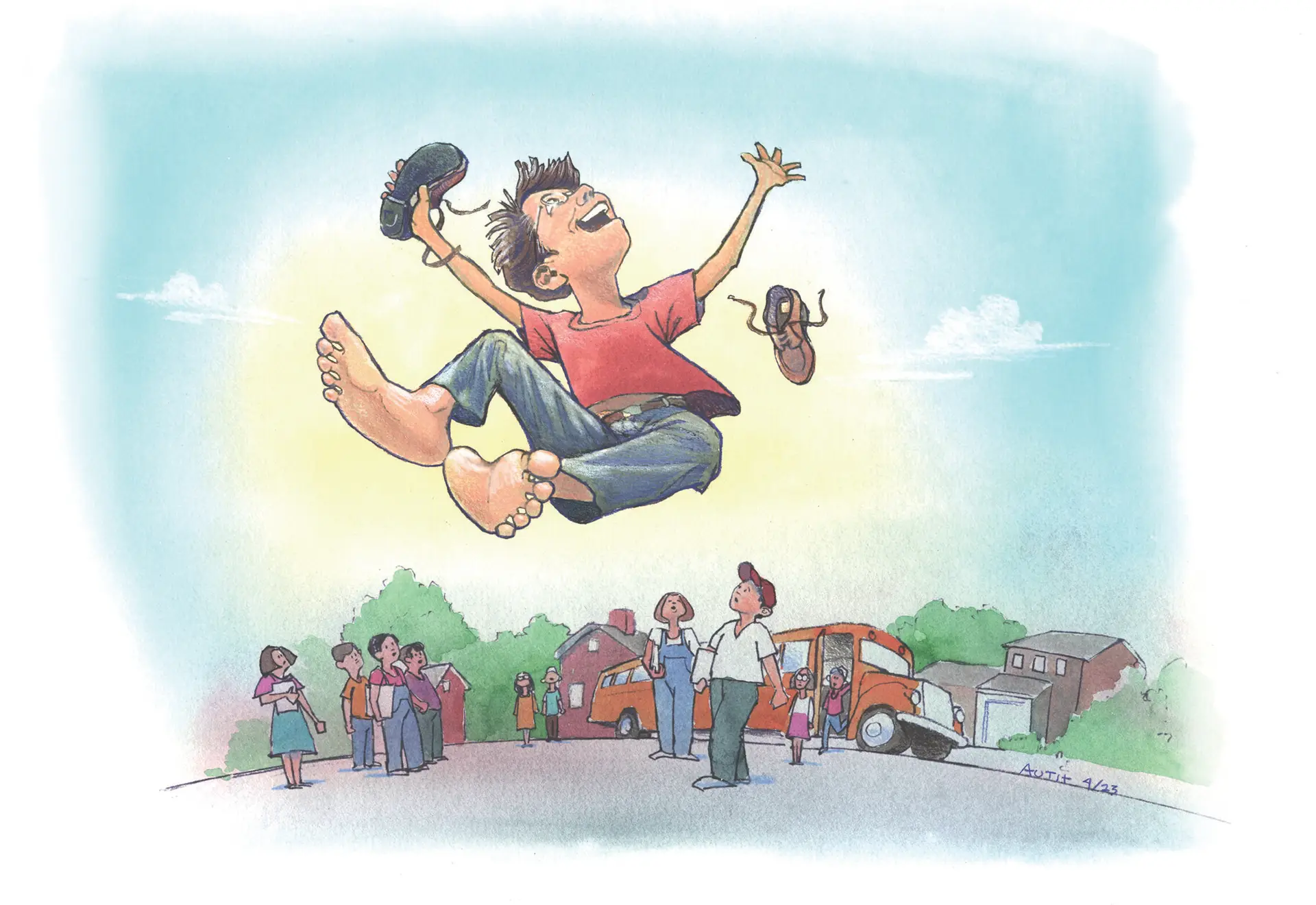

Time to take off our shoes!!

Parents had promised us that our feet could be liberated “after the First of May.”

Anxiously, we waited.

Meanwhile, country kids who rode the bus from cross-road communities arrived shoeless. I never knew if they took off their shoes and hid them until time to ride home, or if parents saw nothing to be gained by children wearing out shoes that should be saved for colder months.

Or for Sunday.

Either way, they went without.

Town children were more closely monitored and did not enjoy such freedom.

I had the best (or worst) of both worlds.

I lived far enough out to ride the bus, but my parents worked in town. They possessed in-town sensibilities, which included wearing shoes.

So, I wore them.

When I left home.

Before the bus arrived, I took them off and hid them to be retrieved when I returned after school.

Then I wore them like the good boy I was.

Or appeared to be.

Harvey H. (Hardy) Jackson is Professor Emeritus of History at Jacksonville State University. He can be reached at [email protected]