Sylacauga prepares to celebrate its famous marble

From the quarries where the marble White as the Paros gleams waiting till thy sculptor’s chisel, wake to like thy poet’s dream. – Julia Tutwiler, “Alabama” state song

By Jim Plott

It may be Sylacauga’s second most famous rock, but considering the city’s most famous rock came from outer space, being number two isn’t too shabby.

Sylacauga marble, the city’s second most famous rock, has been on the scene a lot longer than the 8.5-pound meteorite that fell out of sky on Nov. 30, 1954. That rock punctured the roof of a house and landed on 31-year Ann Hodges while she was dozing on her couch, leaving her with bruises.

And, Sylacauga marble also has a festival in its honor.

For more than a decade, the Sylacauga Magic of Marble Festival has been attracting artisans from primarily the U.S., Europe and Asia who spend two weeks crafting Sylacauga marble into pieces of art.

“We provide the marble, the tools and the work area and it is their job to bring a design that they can complete,” says Dr. Ted Spears, festival founder and chairman.

“It is truly amazing the things they can produce in two weeks.”

While not your typical arts and crafts festival, visitors can visit the tents at Blue Bell Park while the sculptors work. Tours are conducted at the three area marble quarries (Imerys, Omya and Sylacauga Marble) and the B.B. Comer Memorial Library, which houses a collection of marble sculptures. Some marble pieces are also sold at the library.

(As a side trip, visitors can take a free self-guided tour of the Blue Bell Creameries plant which is adjacent to the festival. Tours are best done between the hours of 9 a.m. and noon, Monday through Friday. The plant also has a country store.)

The festival arose out of a cultural exchange with Pietrasanta, Italy, which is near the Carrara quarries where Michelangelo obtained marble for his masterpiece of the Virgin Mary holding the body of Christ, or “Pieta.”

“We invited the mayor of Pietrasantra to Sylacauga and he brought along a dance troupe and a soprano opera singer to perform,” Spears says. “It was so successful that we, along with the support of the state Arts Council, decided to do something on an annual basis.”

Chronicling the marble industry

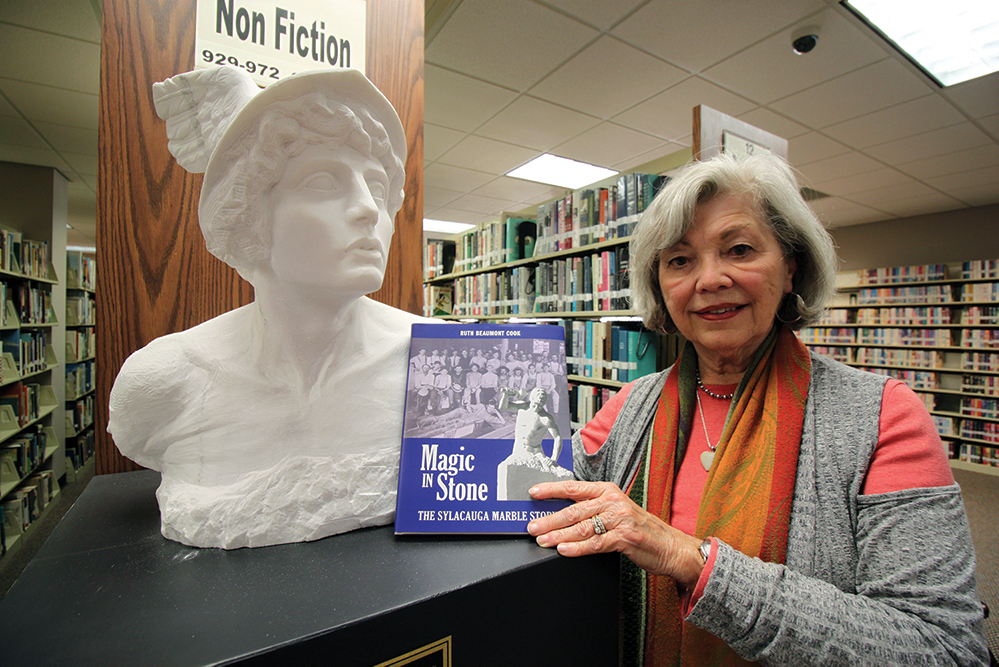

To coincide with this year’s festival, which is March 31 through April 11, NewSouth Books of Montgomery in December released “Magic in Stone: The Sylacauga Marble Story.” Written by historical author Ruth Beaumont Cook, the book chronicles the multiple ebbs and flows of the city’s marble industry and weaves in tales of the people whose lives were influenced by Sylacauga marble, or “Sylacauga white” as some people call it.

Native Americans first discovered the marble, but it was Edward Gantt, a surgeon in the army of Gen. Andrew Jackson, who commercialized it. Cook said Gantt most likely encountered the marble while troops were garrisoned at Ft. Williams near Sylacauga in preparation for the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. When the area was opened for settlement in the 1830s, Gantt returned and founded Gantt’s Quarry. Others established quarries along the 33-mile-long, 2-mile-wide and 400-foot deep marble vein that extends just southwest of Sylacauga nearly to the city of Talladega.

Cook says that in the early 1900s, Italian sculptor Giuseppe Moretti, who created Birmingham’s Vulcan statue, reportedly discovered Sylacauga marble when he saw a Bible crafted from it in the Birmingham office of Republic Steel executive John H. Adams. He had Adams take him to Sylacauga and a love affair between Moretti and Sylacauga marble was born.

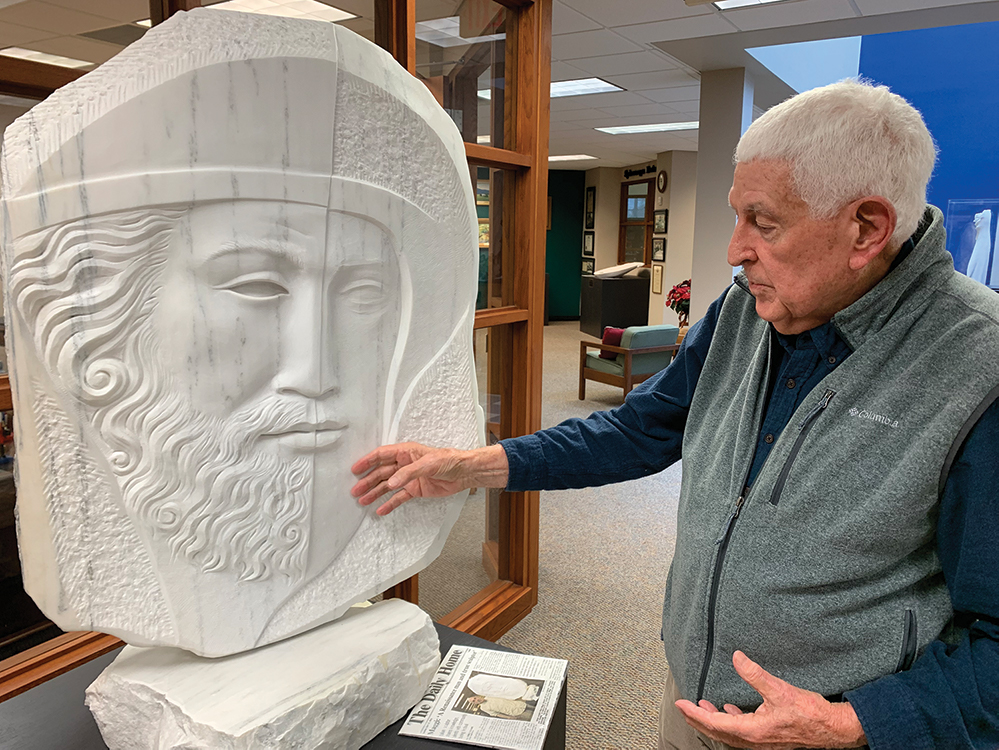

His carving, “The Head of Christ,” was one of his first pieces carved from Sylacauga marble and it accompanied him along with the Vulcan to the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 where both were put on display.

“It is said that he carried that piece with him wherever he went,” Cook said of the carving, which is now on display at the state Archives and History in Montgomery.

Moretti established a quarry in the area where he ran a commercial operation and continued to sculpt. However, a series of consequences resulted in Moretti leaving the quarry and Alabama in the 1920s.

Sylacauga marble can be found all over the world. In Washington D.C. alone, it has been used in some form in the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument and U.S. Supreme Court building, in addition to the state Capitol and the state Archives in Montgomery.

Cook said the translucence and strength are what have made Sylacauga marble popular through the ages.

“Moretti and others have said there are only two other places in the world that have this pure crystalline marble like Sylacauga, and that is the Island of Paros off the coast of Greece and the other is Carrara (in Italy),” Cook says.

Cook says that long before Moretti, Alabama educator Julia Tutwiler made that same comparison and thought enough of the stone to pen a verse to it in what is now the state song, “Alabama.”

Spears said the face of Sylacauga marble began changing in the 1960s when it became more valued crushed rather than in solid form. Although that didn’t go over well at first with many locals, it became a saving grace when the city’s top private employer, Avondale Mills, shut down in the early 2000s.

“Marble has been a boon to us,” Spears says. “Five out of the last six industries that have located in Sylacauga have come here because of the marble. It has saved us.”

And if you doubt that you have ever been exposed to Sylacauga marble, you might want to recalculate that thought.

“Crushed marble is used in everything,” Spears said. “It’s calcium carbonate and it’s used in fertilizers, fiberglass, medicines, toothpaste, chewing gum and even that loaf of bread you buy at the store.”

If the marble festival runs its course, the marble won’t be to blame. Geologists estimate that at the current rate of extraction, there is still enough marble around Sylacauga to last 200 to 250 years.

As to the city’s most famous rock, the Hodge meteorite, it is not totally ignored. In fact, on the grounds of the Sylacauga municipal complex, there is a monument to it – sculpted from marble.