By Marilyn Jones

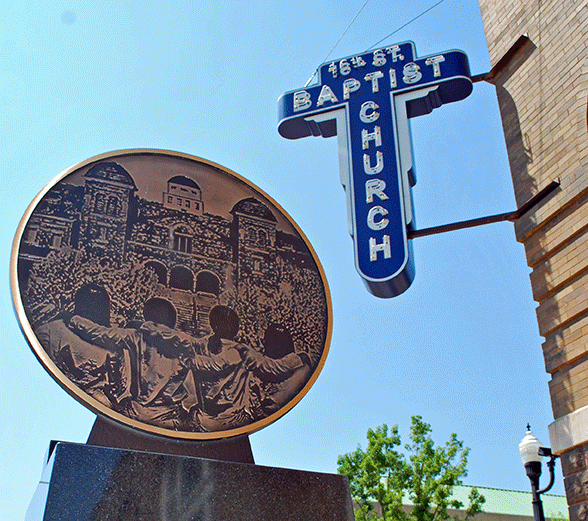

Waiting for the tour to begin, visitors to 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham are able to view the photos, displays and plaques in the Memorial Nook. Everything reflects back to the events of September 1963, a dark and determined time in the history of Birmingham, Ala., and the Civil Rights Movement; a time when peaceful marchers were arrested, white men and women protested school integration, and a bomb took the lives of four little girls.

A young mother reads the plaque bearing the girls’ names to her daughter: “Denise McNair, aged 11, and Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley and Carole Robertson, all aged 14.”

“Why, mommy?” the little girl, who looks to be about six years old, asks.

The more than 30 men, women and children gathered to tour the church wonder, too, what kind of hatred could provoke men to place a bomb outside a church, knowing it was filled with parishioners attending Sunday School.

Abraham Lincoln emancipated the slaves a century before on Jan. 1, 1863 — why were African Americans still being discounted because of the color of their skin?

A church and a city in turmoil

Everyone is asked to gather in the sanctuary where church member Lamar Washington begins telling the group about the church, the bombing and Birmingham.

“This congregation was organized by freed slaves in 1873,” Washington began. “It was the first black church in Birmingham. A church was built at this location in 1880.

This church was built between 1908 and 1911.

“[During segregation] African Americans couldn’t go to city auditoriums, so this church, and other black churches in Birmingham, served as meeting places and social centers,” he continued.

Offering several examples of what segregation meant, he said in 1963 there were no African American police officers or store clerks; they couldn’t use an elevator. “So if my grandmother needed to get to the fifth floor of a building downtown,” he said, “she had to walk up five flights.”

Washington also painted another vivid picture of 1963, describing the carefully planned non-violent protests. On May 2 and 3, 5,000 marchers, many of them schoolchildren, gathered at the church and nearby Kelly Ingram Park to march to city hall. Their efforts were met with high pressure fire hoses and police dogs; many were put in jail. News coverage of the demonstration and the city’s reaction shocked the nation.

Birmingham had a reputation as being one of the South’s most segregated cities. When blacks spoke out, they risked violence from white segregationists. From the late 1940s to the mid-1960s nearly 50 racially directed bombings led to the city’s nickname — Bombingham.

On Sept. 5, two high schools and one elementary school were ordered to admit five black students. Ten days later, September 15 at 10:22 a.m., a bomb blew into the girl’s restroom, killing the four little girls and injuring more than 20 other members of the 16th Street Baptist Church congregation.

The children’s murder brought international outrage that many credit with bringing about the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Before showing a short documentary film about the bombing, Washington tells of the outpourings of sympathy, concern and financial help the church received after the tragedy.

“John Petts of Wales came to Birmingham to help repair the broken stained glass windows,” he said. Petts also created a large stained glass window of the image of a black crucified Christ; a gift from the people of Wales. The window is located in the rear center of the sanctuary at the balcony level.

After the film, Washington invites those who haven’t seen the Memorial Nook to do so, and then quietly leaves the sanctuary allowing those gathered the opportunity to reflect on the events that took place in this church, this neighborhood, this city.

# # #

Birmingham Civil Rights District

A small area of Birmingham is known as the Civil Rights District: 16th Street Baptist Church, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and Kelly Ingram Park at the intersection of 6th Avenue North and 16th Street North, and, a short walk away, the Fourth Avenue Business District and Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame housed in the Carver Theatre.

A visit to this area in the heart of the city helps visitors visualize what happened 50 years ago this year. The physical scars are now covered with beautiful landscaping, statues and memorials, but the underlying message of individual freedom is rooted in the soul of the city — a reminder to never forget.

The Institute tour begins with a short film chronicling Birmingham’s beginnings; a planned city designed around the natural resources available for making steel — iron ore, coal and limestone. Established in 1871 at the proposed crossroads of major rail lines, Birmingham drew men and women in search of jobs in this new industrial city — black and white.

When the film ends, visitors begin a walking journey through the city which, through its many exhibits, relates the Civil Rights Movement and significant events that took place leading up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, subsequent struggles and current world events pointing toward the need for human rights awareness worldwide.

Through a second-story window, visitors have a panoramic view of Kelly Ingram Park; the site where, in May 1963, Birmingham police and firemen, under orders from Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, confronted demonstrators, many of them children and high school students, first with mass arrests and then with police dogs and fire hoses.

Images from those confrontations, broadcast nationwide, brought national and international attention to the struggle for racial equality.

Two blocks away is the Fourth Avenue Business District where much of the city’s black businesses and entertainment venues were located. A highlight of a tour along these historic streets is a visit to Carver Theatre, once a motion picture theater for blacks; it is now a live-performance theater and home of the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame.

Until September 30, the exhibit, “A Place of Our Own: The Fourth Avenue District, Civil Rights, and the Rise of Birmingham’s Black Middle Class,” is also being featured at Vulcan Park and Museum.

When Birmingham was founded, black and white businesses existed side by side. As Jim Crow laws took effect in the early 1900s, a separate black business district emerged for local African-American entrepreneurs. The exhibit helps explain life in the Fourth Avenue District and recalls the successes of business, entertainment venues and cultural institutions.

When you visit

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, 153 Sixth Ave. No.; 16thstreetbaptist.businesscatalyst.com; 205-251-9402. Tours are offered Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. and on Saturday by appointment. Donations appreciated.

Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, 520 16th St. No.; bcri.org; 205-328-9696, ext. 203. Open Tuesday through Saturday 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Sunday 1 to 5 p.m.; Closed Monday and major holidays. Admission charged.

Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame, 1631 Fourth Ave. No.; jazzhall.com; 205-327-9424. Call for tour times.

Vulcan Center Museum, 1701 Valley View Drive; visitvulcan.com; 205-933-1409. Open Monday through Saturday 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.; Sunday 1 to 6 p.m. Admission charged.

More information: Greater Birmingham Convention & Visitors Bureau, 2200 Ninth Avenue North; birminghamal.org; 800-458-8085.

Commemoration event

A commemoration of the 50th anniversary will be Sept. 15 at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Rev. Julius Scruggs will speak at 1 p.m. and a community service followed by a candelight vigil will take place at 3 p.m. Call the Sixteenth Baptist Street Church at 205-251-9402 for more information.