The answer to what’s new with electricity is, as Bob Dylan first sang 57 years ago, “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

The answer to what’s new with electricity is, as Bob Dylan first sang 57 years ago, “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Technology brings history-making updates to the old windmill

This year, wind power will replace hydro for fourth place on the list of fuels used to generate electricity (behind natural gas, coal and nuclear.)

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration projects the growth of wind power will continue into 2020, when it is expected to generate 9 percent of the nation’s electricity.

Wind’s popularity is propelled by the rising interest in renewable energy and improving technology, which has reduced the cost of wind power to about the same price as electricity generated from coal power plants. The federal Production Tax Credit has also driven wind development, and its pending expiration has led to a rush of new projects that will come online over the next few years.

Today’s wind turbines are a lot more high-tech than the old windmills that cranked water up from under farms.

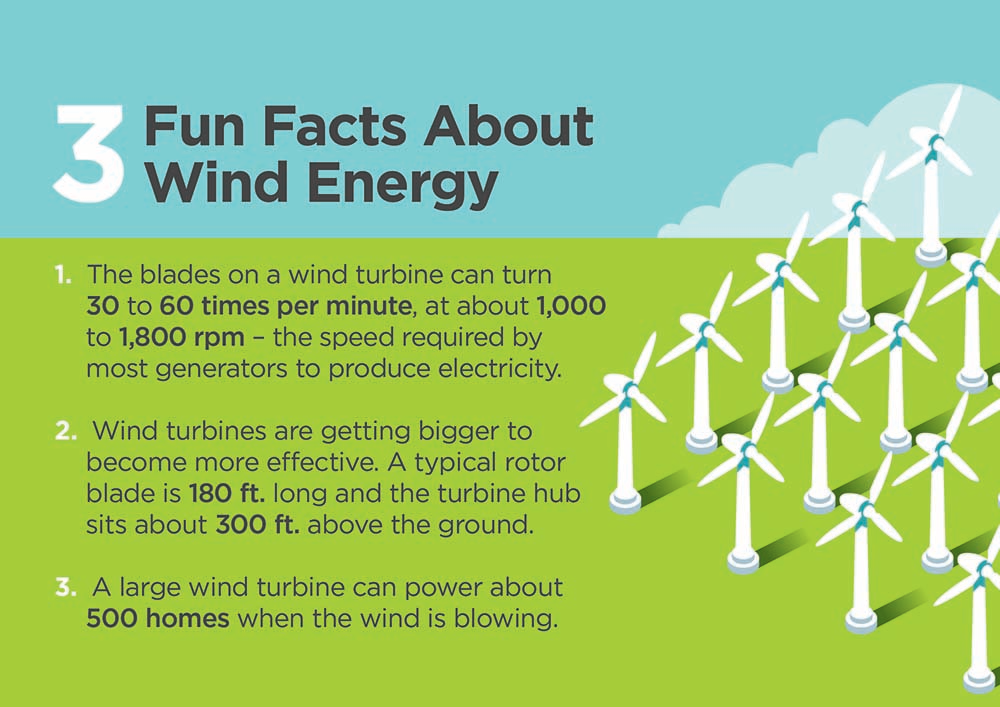

Wind turbine blades are huge, and they’re getting bigger to capture more wind. Over the last 20 years, the diameter of a typical wind rotor assembly has increased from about 75 feet to almost 180 feet. And turbine towers are getting taller, from almost 200 feet to nearly 300 feet since 1999.

Behind each of those rotors is a much smaller turbine, kind of like a miniature version of those that spin to make electricity in a coal-powered plant. The rotors turn 30 to 60 revolutions per minute, and gears inside the turbine ratchet that up to more than 1,000 rpm, which is fast enough to generate electricity. Computerized sensors keep the rotors pointed at the wind.

A large wind turbine can generate enough electricity to power about 500 homes—if the wind blew all the time. But it doesn’t, and that makes wind a tricky power source. Developers hope improvements in large battery technology might store power for use during calm days, but for now, for wind to provide reliable electricity, it needs the help of coal, natural gas and other energy sources that can run 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Paul Wesslund writes on consumer and cooperative affairs for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, the national trade association representing more than 900 local electric cooperatives. From growing suburbs to remote farming communities, electric co-ops serve as engines of economic development for 42 million Americans across 56 percent of the nation’s landscape.