By Miriam C. Davis

From the outside, the building looks much like it did when I was in college and stopped here on my trips from Mobile to Atlanta – a simple box-like, yellow brick structure. An old-fashioned Greyhound sign still hangs in front. Yet there is something special about this old Montgomery bus station, something I didn’t realize then. It was the site of one of the most dramatic episodes of the fight against Jim Crow.

Ellen Mertins of the Alabama Historical Commission welcomes me to the Freedom Rides Museum and explains, “In the 1990s, this building was deemed ‘historic,’ but it wasn’t until 2008 that the Alabama Historical Commission actually got access to it. The museum opened in 2011, the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides.”

Outside the building, panels of photographs and text tell the story: In 1961, Freedom Riders – people committed to non-violence, many of them college students – challenged de facto segregation on the South’s interstate bus transportation system by riding from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans in racially mixed groups. When 20 young Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery on May 20, they were viciously attacked by an angry white mob. The following night, a mob besieged the church in which the black community had staged a rally to support the Freedom Riders. Local police did nothing to restore order until the threat of federal intervention convinced Alabama Gov. John Patterson to send the National Guard to disperse the crowd, allowing the Freedom Rides to continue.

Inside the building, museum visitors can see exactly what the students were protesting. The old “Colored” entrance is bricked over, but one can see that it wasn’t a proper door at all, just a gap in the wall. Diagrams and pictures convey the second-class experience of black passengers. While the main entrance brought whites into a spacious waiting room and dining counter, the opening in the wall for black customers brought them directly onto the bus platform. They had to walk past buses, through diesel fumes, to their smaller waiting room, dining counter and restroom facilities.

When the Alabama Historical Commission established the museum, it decided to focus on artistic interpretations of the Freedom Rides. Mertins says it was a way of drawing in people who might not connect with a traditional history museum. Fifteen local and national artists were featured at the museum’s opening, with exhibits ranging from a realistic bronze sculpture depicting “Liberté,” to abstract works such as “Detour,” a mixed media display of wood, metal, and cement.

Several artists chose ordinary objects to celebrate the extraordinary actions of the Freedom Riders. Cindy Buob’s painting “Objections,” is based on mugshots of four Civil Rights workers and conveys how proud they were to be arrested for their cause. In “By Bus, By Train, By Plane – They Came!” Gwendolyn Magee used a simple quilt to commemorate the names of the 443 “foot soldiers” of the Freedom Rides. Stephen Hayes recycled street signs and an old tire to represent the road to equality in his abstract sculpture, “Detour.”

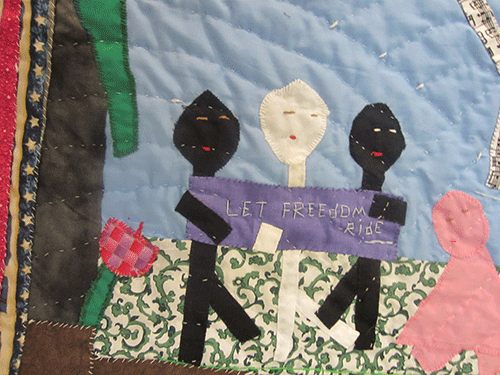

The artists’ exhibits change every year, renewing the museum experience with fresh perspectives. On my recent visit, I was struck repeatedly by how everyday objects can be transformed to examine and celebrate the extraordinary. One permanent collection piece, Terry S. Hardy’s “Monument,” is constructed with a stack of old suitcases to represent the histories of those traveling on the road to equality. Artist Charlie Lucas used scrap metal to convey the story of the Freedom Riders in “We Ride Together,” a metal sculpture of a Greyhound bus. Quilt artist Yvonne Wells tells the story of the young activists who persevered against angry mobs in “Let Freedom Ride II.”

My favorite exhibit is by photographer Eric Etheridge. He paired mug shots of the original Montgomery Freedom Riders with recent photographs of them. Life went on for the movement’s heroes, who became pastors, teachers, and business owners – people one might take for ordinary – but who faced very real violence with the gospels of non-violence and equality.

Ultimately, the Freedom Riders’ mission was a success. The violence at the Montgomery Greyhound station inspired more riders to continue the journey from Montgomery into Mississippi. The attention these activists brought to the injustice of segregation led the Interstate Commerce Commission to rule that all facilities in interstate travel must be integrated.

Today, visitors come from all over to learn the story of the Freedom Rides. Take a tour led by one of the museum’s staff. Wander into the “Share Your Story” kiosk and listen to the reminiscences of the Freedom Riders, or record your own reflections on what you’ve learned.

You’ll never look at this ordinary bus station the same way again.