By Miriam Davis

“The tiger saved us,” says Command Sgt. Maj. Bennie Adkins (U.S. Army, Retired) matter-of-factly. “The North Vietnamese soldiers were more afraid of it than they were of us.”

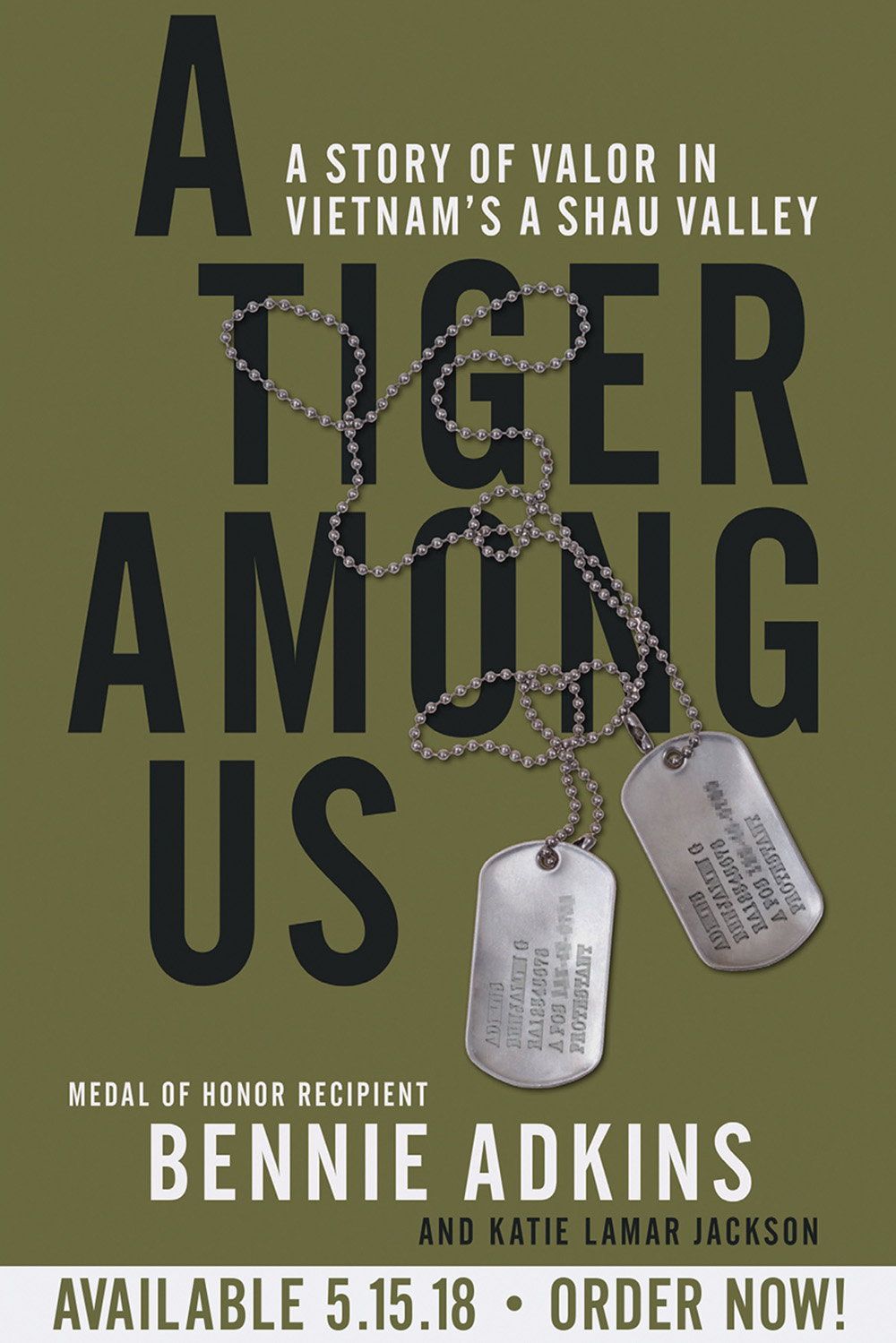

Adkins, 84, is speaking of the aftermath of the Battle of A Shau when, in 1966, he and other survivors evaded the enemy after a team of 17 American Special Forces and about 400 of their South Vietnamese allies were attacked and overrun by a North Vietnamese division of 16,000 troops. In 2014, President Barack Obama awarded Adkins the Medal of Honor for his actions during that battle. Adkins and co-author (and Alabama Living gardening columnist) Katie Jackson tell his story in their forthcoming book, A Tiger Among Us.

“I was just doing my job,” insists Adkins. “It was my training. … When you’re picked out to be one of the elite, you try to live up to that.”

Adkins’ job was as a Special Forces intelligence sergeant. After being drafted into the Army in 1956, he found being a clerk-typist “not for me.” Special Forces was a challenge both physically and mentally. But, says Adkins, “I had too much pride to quit.”

In 1965, then-Sergeant First Class Adkins was sent to the A Shau valley to advise South Vietnamese forces and to impede infiltration of the North Vietnamese into the south. The valley, which runs along Vietnam’s border with Cambodia and Laos, became part of the trail along which the North Vietnamese brought provisions and troops down into the south and as such was, as Adkins describes it in his book, “a hotbed of activity.”

“I can tell you that none of us were happy to be in that camp,” Adkins says in A Tiger Among Us. Sitting in that valley, “about thirty miles from another friendly camp …. [w]e were like fish in a barrel.”

Risking his life

Adkins’ team had been warned that an attack was imminent, and the Battle of A Shau began about 4 a.m. on March 9, 1966, with a deafening North Vietnamese artillery and mortar barrage. Adkins ran to take his position in a mortar pit from which he and his crew fired illumination and high-explosive rounds.

Wounded 18 times, Adkins repeatedly risked his life during the battle. He was blown out of his mortar pit three times by direct hits from enemy mortars and lost several entire mortar crews. But he continued manning his position until the mortar pit was finally destroyed by RPGs (rocket propelled grenades). Disregarding enemy mortar and sniper fire, Adkins also rescued American and Vietnamese wounded and transported them to safety, and then – again under direct fire – loaded them onto evacuation helicopters. When a load of desperately needed supplies was inadvertently dropped into a mine field, Adkins rushed into the mine field to retrieve it.

After 38 hours of intense fighting – hungry, thirsty, and exhausted – the Americans were ordered to evacuate. In the chaos of the withdrawal, Adkins went back to rescue a badly wounded comrade. When they returned to the evacuation point, the helicopters had already gone.

Which is where the tiger came in.

Adkins and a small group of survivors had no choice but to evade the North Vietnamese in the dense jungle until they could be rescued. On their second night, Adkins and his men could hear enemy soldiers searching for them. They also heard another sound – something big rustling in the undergrowth nearby. Then Adkins heard a low growl and saw eyes glowing in the dark – a tiger, drawn by the smell of blood covering the wounded survivors. The war had given tigers a taste for humans.

The North Vietnamese heard the tiger, too, for they hastily pulled back, allowing Adkins and the other survivors to slip away. They were picked up by helicopter the next day.

Shortly after the battle, Adkins was nominated for the Medal of Honor. Nothing happened at the time. But in 2014, Adkins received a phone call from President Obama informing him that he was to be awarded the nation’s highest military honor.

“Super humbling,” is how Adkins describes it. “I’m very humbled to be one of the few living soldiers to wear this medal.” He now speaks all over the county trying to inspire in people a love of country and the desire to be a good citizen.

“And an appreciation of the military,” adds Adkins’ co-author Katie Jackson. She points out that less than 1% of the population has served in the military and that “the general population doesn’t understand the military.”

Adkins and Jackson, an adjunct instructor in Auburn’s School of Communication and Journalism, worked on the book for three years. This involved tracking down and interviewing the five other survivors of the battle. “All of them have a deep admiration and respect for Bennie,” says Jackson. “Even years later, they all say he’s amazing. … He was the one who really did things that were superhuman.”

Last year the foundation awarded the first scholarships; 25 will be awarded this year.

All of this was made possible by the 400-pound Indochinese tiger that saved Bennie Adkins all those years ago.

“That tiger was my friend,” chuckles Adkins.