Author documents history of state tourism

By John Brightman Brock

Tim Hollis, a magazine editor in Walker County, years ago set out to preserve his family’s past. He ended up preserving the past for his fellow Alabamians.

Tim Hollis, a magazine editor in Walker County, years ago set out to preserve his family’s past. He ended up preserving the past for his fellow Alabamians.

At age 9, in 1972, he chronicled his family vacations from when he was 3. Today, at 51, he has a museum of tourism memorabilia at his residence. It is the same home where as a toddler, he was suited up to join his amateur photographer/teacher father and a not-so-fond-of-traveling mom as they hit the road … to see Alabama.

Hollis started actively collecting in 1981, his first year in college. His family memories, assisted by carloads of archival files given to him by the Alabama State Department of Tourism, fueled his desire to write the definitive Alabama tourism book, his 22nd book.

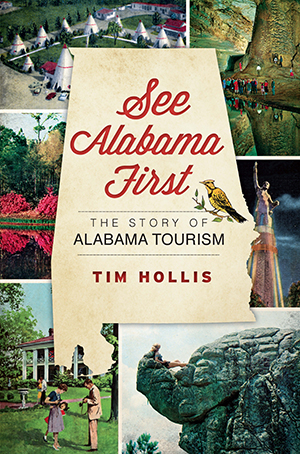

See Alabama First, The Story of Alabama Tourism will be the focus of an Oct. 16 Architreats discussion program at the Alabama Department of Archives and History in Montgomery. The self-acknowledged “pop culture” author plans to delve deeply into his book, which harkens back to a simpler time of flashy roadside attractions popping up everywhere, including the “wigwam” replica motels that sprouted up to lure the tired traveler. Those were the days when, along roads like Highway 31, there were no posted speed limits, just what was “reasonable” to the driver.

“It’s going to bring back so many memories,” the author said in a telephone interview from his home located between Birmingham and Jasper. “Especially if they (readers) grew up in the state. So they can remember and now see what they missed. So much of this stuff … came and went.”

Putting history together

The book keys on Alabama’s at-first small tourism emphasis, pausing for strong looks at places like Bellingrath Gardens, near Mobile, which began as a location for locals to discover. See Alabama First examines in chronological order a changing Alabama highway and tourist landscape starting from the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s. As for Hollis, he relates most easily to the ‘60s.

“I have always put history together,” Hollis says.

At Hollis’ request, Alabama tourism officials turned over a huge amount of memorabilia. File cabinets full of information revealed, among other things, that politician John Hollis Bankhead in 1916 ensured that one of America’s first transcontinental highways went through Alabama. “By 1926, (highway) numbers were replacing names throughout the country, including in Alabama,” Hollis writes. “The process of numbering the highways was not done by some willy-nilly, pull-a-number-out-of-a-hat method. The first decision was that highways running north-south would have odd numbers, and east-west highways would bear even numbers. In Alabama, the former Bankhead Highway largely became U.S. 78. The Lee Highway became U.S. 11 and the Andrew Jackson Highway was U.S. 31. The former Old Spanish Trail was U.S. 90.”

Alabama for years had been a state that people passed through on their way to somewhere else, he says, never coming to places like Vulcan Park (in Birmingham) or Ave Marie Grotto (in Cullman) to vacation. Sometime in the late 1940s or early ‘50s, state officials figured it out. In the early ‘50s, Alabama instituted posted speed limits.

Memories for more than just one family

During his childhood, Hollis’ family went to Gulf Shores a lot. He saved postcards and brochures. His dad’s 35mm camera images became “in many ways, the record of my life.” His dad once noted on a postcard that the family “had watched the astronauts land on the moon in our room at a Holiday Inn. (Well, the moon wasn’t in our room, but you know what I mean, so lay off the smart remarks),” Hollis writes.

The book is peppered with astounding photos, like the one of the 56-foot-tall cast iron statue of Vulcan – his favorite memory – mounted on a 124-foot pedestal, on the crest of Red Mountain, overlooking U.S. 31. A 1954 brochure about Alabama’s first Holiday Inn, between Birmingham and Bessemer on U.S. 11, was “more elaborate than most,” having 82 rooms, a candy shop, lounge, library, drugstore, barbershop, gift shop, beauty parlor, assembly hall, and a 24-hour service station.

Hollis has turned his home into a collection point for all things pop culture – a preservationist mantra he adds to on weekend trips to this day.

“I live in my own memories, someone told me,” he says, pausing. “When I first started, I preserved my own memories … and I realized I was collecting other memories, too.”

See Alabama First, The Story of Alabama Tourism is available at local stores and online at www.historypress.net.

Tim Hollis supplies the nostalgic materials for the popular www.BirminghamRewound.com website, through which he may be contacted.